From the Eiffel Tower in Paris you can see an artwork on the museum roof of the Musée du Quai Branly. It's a piece by Australian Aboriginal artist Lena Nyadbi. This is a powerful symbol of the level of international respect achieved by the contemporary Australian Aboriginal art movement.

This is the story of how it emerged.

If you go back in history to 1980, very few white Australians would have seen real examples of Aboriginal art. So what is the history of the Aboriginal art movement? How did it emerge and take the world by storm?

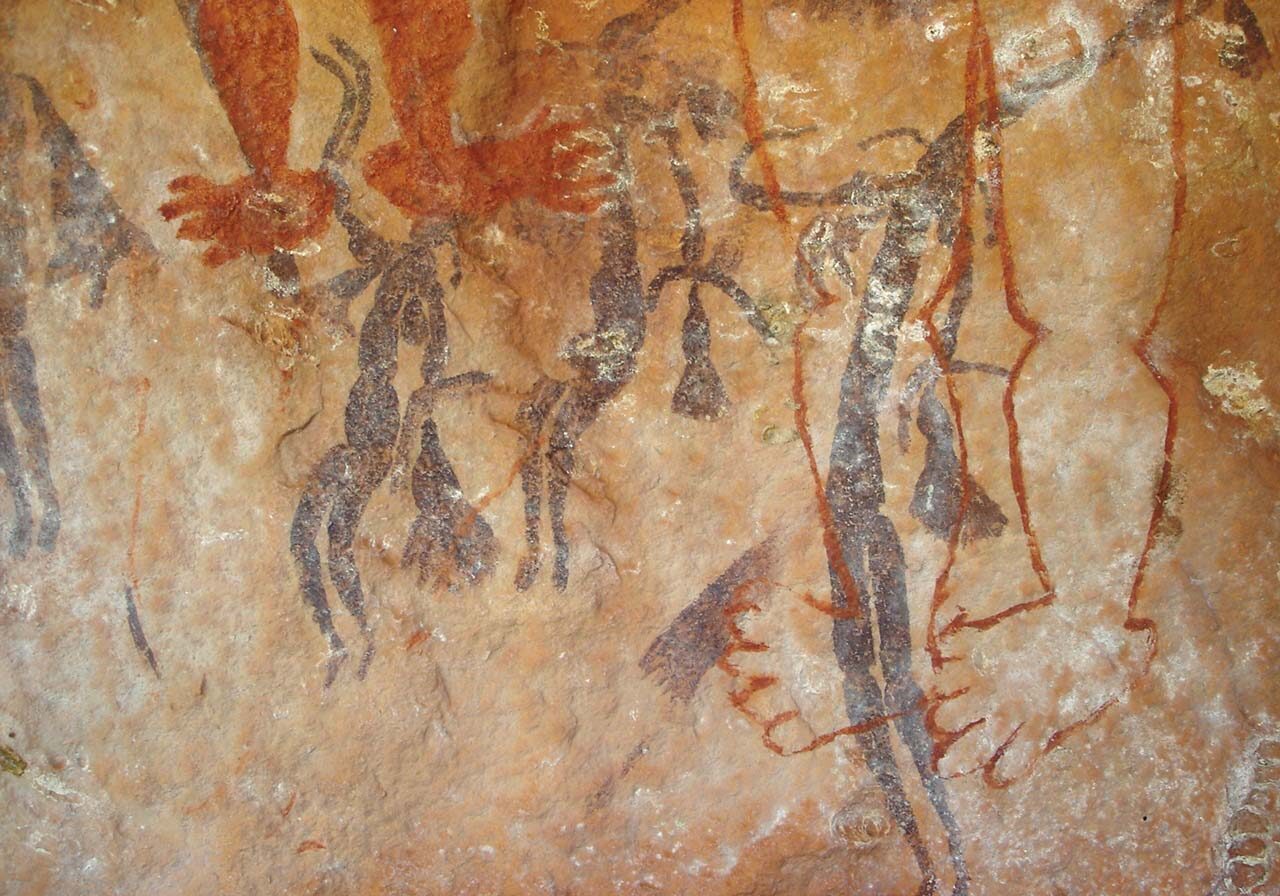

Aboriginal Art is the Oldest Art

As of late 2015 some Aboriginal art rock paintings are looking like they will be dated and proven to be the oldest art by human beings in the history of the planet - by some thousands of years.

Indigenous culture is based on strong ties to the land and documenting the changes, the seasons, the animals and the spirits that reside in nature and in the land. It’s not an ownership of land but more a custodianship. These stories were recorded mostly by drawings on rocks. At the time there would also have been body painting and sand painting as well as other art that was part of rituals and ceremonies that invoked the spirits. So Aboriginal people have been communicating in pictures for a very long time.

Art Is a Strong Platform For Aboriginal Culture

There are no records of written Aboriginal languages. Rock pictures were a visual form of communication. Aboriginal rock art is a pictorial representations of aerial views of the land, the animals they hunted, animals that they venerated or those that were their specific totem. These images have always played a big part in the culture. It’s been integral to the culture as much as the spoken language is. In some ways it’s very different to many other cultures because art was one of the main platforms of the culture.

Art Hidden From The West

This painting tradition continued on, mainly hidden from western influence. It is tucked away in sites in remote locations in caves and on rock carvings. Unfortunately drawings and carvings done on wooden implements and artifacts such as shields have mostly gone. They’ve perished with time. We’ve not found those. What was done on more permanent mediums, carved into rocks, does still exist. Now they’ve finally been dated and we've come to appreciate that the Aboriginal culture is very likely to be the oldest on the planet.

Cultural Ties Begin To Break

Westerners arrived in Australia in the late 1700s and progressively settled across the land. How the indigenous people were treated varied from region to region. In some cases there were massacres of family groups. There was enforced labour where wages were withheld or never paid. Some communities endured the forced removal of children. Children were forbidden to speak their traditional language. There was no respect shown for traditional culture and it was systematically undermined by administrators and policy makers right up until a gradual change in attitude from the 1970's.

Given the relentless and debilitating pressure and attack on Aboriginal culture it is not surprising that the indigenous art tradition fell a bit to one side. Many indigenous people still carried on their art as it formed part of their ritual life. However, over time and in the face of opposition, it was gradually forgotten about. It became less and less understood, even by some indigenous people, as western influences became increasingly dominant in their lives.

As Westerners took over the country they pushed a lot of the indigenous people off their traditional lands. Some cultural ties became broken, some parts remained really strong. There are parts of Australia where the strong ties were almost completely lost. This was more likely to occur in heavily built up urban areas around Australia. It is very hard to find traditional art on rock faces or carvings anywhere in these environments. Those that still exist are probably there because very few people know where they are. So for many indigenous communities those traditional art links became broken or increasingly very fragile.

Culture Remains Strongest In Remote Communities

Out in the desert and in the remote Kimberley and in Arnhem Land, it still flourished. It was still strong but it was being undermined by western culture and the lure of television and sports and everything else (both good and bad) that the west has to offer. These are mostly materialistic influences. However they present a strong pull and it was becoming stronger especially for the younger indigenous people.

The traditional respect for elders was also breaking down because many younger people were not being initiated anymore into the traditional ways. The old people, probably the last generation who were born in the desert, have no birth certificates, they were fully initiated in the traditional ways. They are a direct and very personal link to a culture that goes back 60,000 years. In many communities the western influence had led to a decline in the respect for these elders and their traditions. There was a significant risk that traditional knowledge might have ended with the death of these old people had things continued on the way they were going.

Papunya Sparks A Change

Papunya was a turning point in this story. School teacher Geoffrey Bardon was posted to this remote community. He realised the significance of art to indigenous people as a language. He could also see that this link, this unbroken link was being eroded. He was concerned. Initially, he worked with mainly senior men. Those discussions convinced the artists that they should start recording the art and the stories associated with the art, because the two are strongly interlinked. He encouraged them to use more permanent mediums such as canvases and boards and to use acrylics for the first time rather than traditional ochre pigments.

Elders Make A Critical Decision

The senior law men of Papunya met and considered what stories could be shared and what should remain secret. They decided to embrace this idea of painting their stories. This was a very powerful decision.

There were a couple of different reasons behind that significant choice. Mostly they wanted a permanent record of the culture. That was clearly the strongest incentive. They wanted the next generation to see what the stories were, what the art was and how they depicted the Ancestor creator spirits. Primarily most of these paintings are aerial views of the landscape but not just the physical landscape, they were also metaphysical and intensely spiritual. It was really important to preserve these stories, everyone could see that.

There was also financial incentive because Geoffrey Bardon suggested that there might be a market for these paintings. This was by no means a certainty. There are stories about Bardon bringing the paintings to town and calling his friends to ask them to come and buy the pictures. As he loaded up his car for those early trips Bardon could have had no idea that those early works were the beginning of a new wave of Australian art.

The New Art Spreads

Those early works were initially done by the Pintupi people and other language groups at Papunya. The painting soon spread to the Warlpiri people out at Yuendumu. They became quite famous for painting the doors of the local school with traditional patterns and stories. For a lot of the children, it was the first time they’d openly seen art by their own people. It was very powerful. These doors are now in the National Museum and other major galleries. They are historic and very important pieces of art.

Read:

Yuendumu Men’s Museum and Western Desert Art

Aboriginal Dot Painting in Central Australia

Of Country and Culture: The Lam Collection of Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art

The traditions of many Aboriginal groups were so fragile at this time. They could have quite easily been lost. If more indigenous people had fully embraced western culture and let their traditions go it would be lost. We would have had little idea what it all meant. It would be lost to us all forever.

Papunya Elders & Geoffrey Bardon

It was those early decisions by the Papunya elders combined with the facilitation of Geoffrey Bardon that meant many of the traditions are now recorded and passed down. The new painting movement has been taken on by one community after another. I think this will be looked back upon as the golden age of indigenous art. That’s when all the elders started to paint and record these stories before they were lost. It was a real flourishing of art and each region has its own style, each region has its own stories. It really captured the imagination of communities right across Australia. It caught the attention of the art world in Australia and overseas as it grew and grew.

Read: The Early Influence of Geoffrey Bardon on Aboriginal Art

Vibrant New Interpretations of Ancient Stories

This success story almost didn’t happen. I can’t believe how much poorer we’d all be if this important cultural heritage wasn’t protected and nourished and continued. The thing about it is it’s not a static culture. We’re sitting here in a gallery surrounded by bright colourful paintings and this is certainly not what you would have seen back in the 1970s. The symbols in these paintings you would recognise because they are the same. However, the younger generation has now adapted the stories. They’ve been passed down to them. They are now the legal custodians of these stories. They are interpreting them in their own way. They bring a freshness to the telling. These stories may be as much as 60,000 years old but they still have a vibrancy and life of their own.

A Living Culture

Australian Aboriginal culture is very much alive and evolving and changing and adapting to to the 21st century. Part of its strength is that it can adapt and still maintain its integrity. The stories behind the paintings are really just the skeleton of the story. We don’t know the full story and unless you’re initiated, you never will. What the artists are sharing with us is those bits that aren’t sacred. They’ll give you an outline of what their culture is and what the story is, but there is a part of it that is kept secret.

Regions Have Identifiable Styles

From that really small start in Papunya this art movement has gone on and spread to communities of Aboriginal peoples around Australia. Regions often have their own identifiable style. You can often look at a painting and say, oh yes, that one’s a Pintupi artist or that one’s Warlpiri, or this one’s from Utopia. All these regions have an identifiable style. Sometimes it’s really obvious, sometimes it’s in the symbols they use and the iconography. An example of an obvious one is from Arnhem Land where cross hatching is used. It’s so different from the dot paintings.

Style Is The Artist's Signature

When you see the cross hatching, each one is subtly different, it’s like a signature. That’s an obvious signature whereas all the paintings in our gallery have no visible signature on them at all. People often say to me, why don’t the artists sign it? That’s a reasonable question. People have been brought up in art to expect to see the artist signature in the corner. To these artists it’s not necessary at all because as far as they’re concerned only they can paint that painting. That’s because they are the traditional custodians and that painting could only be done by them because they are the recognised custodian of that particular Dreaming. They don’t have to scribble their name.

Importance of Reputable Galleries for Aboriginal Art

In some ways it’s a little bit sacrilegious to scrawl your name across a spiritual painting. It would be like Michelangelo scrolling his name across the Sistine Chapel. It’s not like that and it’s not necessary. Western people of course want to know that the painting is by who they think it should be. This is one of the main and most important reasons why people should only buy Aboriginal art form reputable galleries whose members follow a recognised Code of Conduct. You do need experts to guide you in this very complex field.

New Styles Emerging

New styles are emerging all the time. Probably eight or nine years ago, the Western Desert artists took the indigenous fine art movement to a different and a new level. They had a different look and style and feel and a very distinctive palette to what had preceeded them. Every 5, 6, even up to 10 years there can be different art movements that capture the public's imagination. There are still many other communities at the moment who aren’t painting who don’t have art centres and yet there are so many people within those communities who have an immense innate talent. That to me is one of the most staggering things, the incredibly high percentage of indigenous people who seem to effortlessly display visual acuity, such a high proportion are great artists.

Many With Artistic Talent

I believe the reason that so many Aboriginal people are gifted painters is because they come from a culture where communication has always been at least in part through a visual form. It’s completely different to my experience in western culture. There are so few western people who have this visual acuity or ability to paint a great picture. You have to remember very few of the artists we exhibit at Japingka have had any formal training in art and yet their work is stunning. It attracts international attention. It also helps that these amazing artworks can be appreciated on several different levels. You can also appreciate most of these paintings as abstract paintings (of course they are more landscapes, than abstract paintings). However, they work on that level incredibly well. The balance, the surface tension, the palette, the way the colours interplay and work off each other, it’s all there but it’s innate and intuitive. It’s a real skill.

Complex Work With No Training

Sometimes people with little or no experience or knowledge of Aboriginal art and culture sometimes think these are simple paintings and it must be easy to do. I challenge anyone to go out there with a blank piece of canvas and come up with an original idea that tells a story, not just copying. However it is a different story to create something from nothing but a blank canvas. Especially something that hangs together like these paintings do. Often, the artists put together colours you don’t think would work together, but their innate sense of colour means that they do.

The way all the symbols are placed over the canvas brings you that surface tension, that completeness. I’m forever staggered at the talent, the innate talent. It looks effortless but it’s not. It's just incredibly skillful. I know some western artists feel the same way. I think part of the reason Aboriginal art carries so much strength is that it’s coming from such a deep spiritual place in the people. That is a large part of its power.

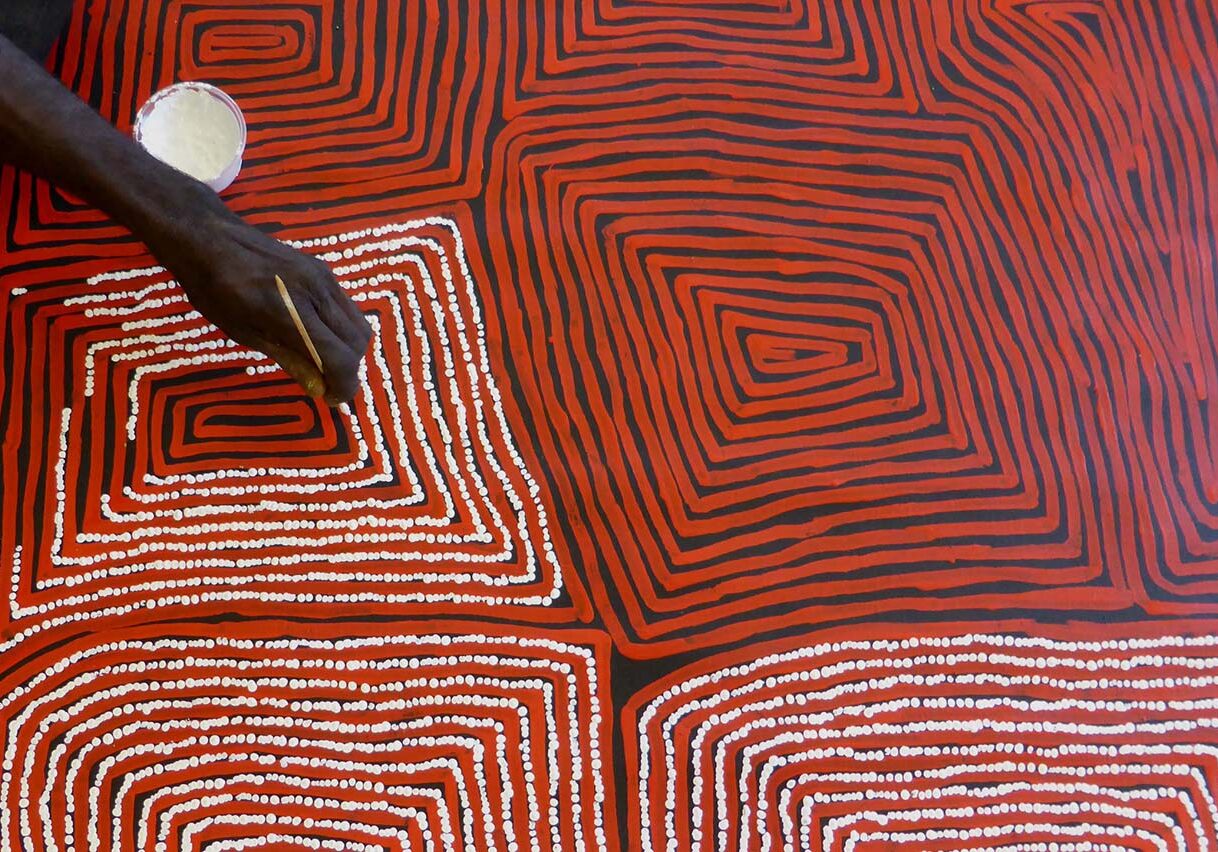

Elders Painting

I have certainly felt this power when I was watching the older people paint. There was this ownership of the Dreaming story because only they could paint it. With that came a real sense of confidence because if they said this is the way it is, then that’s the way it is, because they are the custodians of that Dreaming. I remember watching an older woman paint and she was sitting on the ground with all the colours around her and it’s almost like a blur. If she goes from one brush or a stick to another but all the time she’s singing the song associated with the story.

Passing Knowledge On Through Song

It’s like a book because it’s the passing on of your knowledge from one generation to the next through oral tradition. A song is one of the ways to remember words. It helps to get the order right, every verse after the other and the chorus. A woman will often have her family around her when she paints and sings. They learn the words while she paints. She’ll sing to them about the story and they all join in. That’s how they learn the words. It’s a real privilege to be there and see something like that taking place. The knowledge is directly passed on even to the youngest little girl who might be 2 or 3 sitting there. She’s already being inculcated with the rhythm of the land, the song and the art and the colours. It’s an amazing way of starting life and maybe that’s where part of the visual acuity comes from.

The Aboriginal Art Movement Spreads Across Communities

From very small beginnings, that little place out at Papunya was the start. Then the art then spread to Yuendumu. From there it continued spreading around all the communities. Initially it was Central Western Desert art, strong motifs and symbols. Really, the story was in some ways more important than the art. It worked really well as art but at this point the colour palette was still quite limited. Even though the artists were working in acrylics, they were still using the colours of traditional ochre pigments. This was fairly limited palette of up to 8 colours at the most.

Jimmy Pike & Colour

It’s hard to put an exact date on when the ochre palette changed and we started to see more colours. For me it was when we were working with Jimmy Pike back in the 1970s. He was a famous Walmajarri elder who went on to become a well known artist. At that time he was in prison and my co-director in this business David Wroth was a printmaker and an art teacher in the prison. He met Jimmy Pike through the prison art programme.

Jimmy was as a traditional law man, an elder and a very spiritual man. He was highly respected. Here he was in Fremantle prison, a long way from his country up in the Kimberley. He missed it dreadfully. He really did pine for it because he wasn’t on his country and he was stuck in this prison, thousands of kilometres from home. He fully and enthusiastically embraced the art classes that Stephen Culley and David Wroth were providing to the prisoners in the Fremantle prison as a way of both recreating and reliving his stories, culture and country.

Texta Colours

Jimmy wasn’t particularly interested in ochre colours. He wanted to use texta pen colours. He liked to create pictures of his country and the traditional stories. Most of his people, the Walmajarri people, hadn’t lived on their country for maybe 40 or 50 years. There was a big migration up to the mid 20th century when his people heard about this easy tucker and flour and everything else that was available in the settlements. It went through all the desert communities like wild fire and they gradually migrated out of the desert towards the cattle stations and regional towns.

Other communities were moved by force. This was imposed on them by the government of the day. Sometimes it was because of perceived overcrowding. A lot of people from Yuendumu, Warlpiri people, a big group of them were forcibly rounded up and moved off their land. I can’t say what the thinking behind it was. Those people were moved further north towards Katherine to Lajamanu in the Northern Territory. This was hundreds of kilometres away from their traditional country.

They were moved into country that belonged to people of a different language group. The authorities had displaced them. Lajamanu community is still there, I wouldn’t say it’s flourishing but it’s there. Some great artists come from there but they are all displaced people. Just seeing how Jimmy Pike was so emotionally affected by being off his country, you could imagine the turmoil and the grief this displacement caused.

Jimmy Pioneered Use of Bright Colour In Indigenous Art

As far as I can see it was Jimmy Pike who first started working with a lot of colour. He loved textas and the vividness of the tones. He really loved colour. Jimmy made works on paper as well as linocuts. There are quite a few prints made of his work. He brought strong vibrant, almost neon-like colours into his art. Up until this point indigenous art was mostly associated with browns and yellows and he transformed it.

For this reason I think he was a truly pivotal artist in the indigenous fine art movement. I don't believe that he hasn’t been properly credited with the way he changed and inspired the whole Indigenous Fine Art Movement by boldly introducing colour. Not just a little bit here and there but saying, well, this is what the country is like sometimes. Sometimes it’s full of colour, strong bright colours. That was Jimmy’s work.

Great Art Movement

Not every community changed their palette. Even today we meet artists who still work in the natural ochre pigments and others who, even with access to acrylics will still only use 5 or 6 colours. This is a traditional approach and what they feel comfortable with.

However, these days most indigenous artists have moved to using all the colours available to them. As a group of artists, they are very adaptive. The broadening of palette was a major change in the movement. It wasn’t long before an Australian, who was also an international art critic, called indigenous art the last great art movement of the 20th century. Others have gone on to say it is the first great movement of the 21st Century. It’s not the same movement all the way through. New bits keep coming on, new communities emerge, new styles emerge. The only common factor is that they are done by indigenous people.

Diversity of Styles

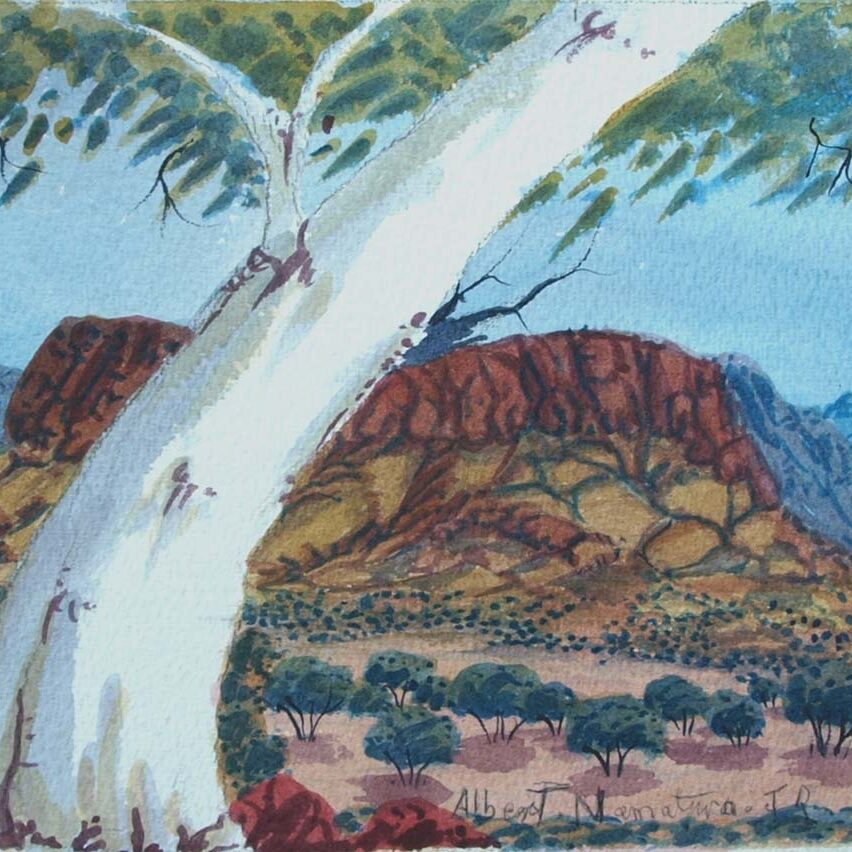

The styles are so varied and diverse. They tell so many different stories. They have so many different influences. When I was growing up, indigenous art was Albert Namatjira and his watercolours from Hermannsburg, south of Alice Springs. They were on first appearances, essentially western style art, and yet he was famous as a watercolour artist. He was an artist painting in a western style - and to some extent, he just happened to be indigenous. However, it was more than that. It was also his undoubted ability to capture the essence of the landscape that he was painting. He would have been for many Australians the first indigenous artist people had heard of or knew about. He became very famous in Australia and his artworks fetch tens of thousands of dollars now. While plenty of other western artists have gone out to the same country and painted in watercolours it is Namatjira’s work that stands out. It demonstrates an understanding and connection to the land.

Albert Namatjira and International Fame

While Western artists might achieve a similar level of technical skill, they don’t seem to capture the Australian light or the feeling of the land in the way that Albert Namatjira was able to. Albert started his own school of art, and it continues to this day. Artists at Many Hands Art Centre are still producing beautiful watercolours of the country around Alice Springs, the waterholes and canyons. They are still painting the ghost gums that featured so heavily in Albert’s work. The tradition is definitely being carried on. A tradition that has adopted western styles of painting and woven it into something that is innately Indigenous.

International Reputations

Indigenous art has gone beyond painting to other areas like ceramics, textiles and glass. In terms of painters, Emily Kngwarreye, Clifford Possum, Rover Thomas are some of the most famous artists. Their works have been internationally accepted and acclaimed. Works by Clifford Possum and Emily Kngwarreye were purchased for over $1 million, and Rover Thomas has fetched $750,000 for natural ochre paintings. In some ways, it’s a success story that has happened in remote communities. In fact I know, other that the odd community that’s lucky or unlucky enough to have mining nearby, it’s the main form of independent income in these communities.

The artists are role models within the community. These older people have become very successful and famous. They’ve come from a community that might only be 50 people in the middle of nowhere. They’ve got an international reputation, they are known in London, they’re known in Paris. This is all quite remarkable.

Breathing New Life Into Culture

The art movement has drawn the youth back into having an interest in traditional culture. It has renewed and strengthened the story telling tradition. There have been big changes in the culture because of western influence. In western culture there is no longer a lot of respect for older people. That line of thinking may have influenced a lot of the indigenous people too. They might think, “What would you know old fellow”?

The fact is the old fellow knows so much, it’s immeasurable. That’s become clear because these older people are being highly regarded by people from around the world, people that the younger people respect. The paintings of community elders are attracting the attention of rock stars, art critics, the National Gallery, major auction houses and major collectors. There’s also the money that comes with that too. It is a success model. Not everyone is an artist but for many painting is a career option. Younger people then have a ready made role model right in their own community who’s shown them how to do it. However, they can’t just paint, they also have to be initiated into the culture and be a custodian of a Dreaming story to be able to paint it. So this also helps draw the next generation into learning and respecting their own amazing culture. In the end, its about pride and respect.

The Pull of Western Culture

Western culture offers the seduction of a fast lifestyle, drink, drugs and all those sort of things at one end of the scale. At the other end there is the pull of sport which is also attractive to younger people. These are all things that can take people away from the culture and from their land. Art has put another option on the table. Now artists can stay on country, keep culture strong, continue the culture, paint the stories.

The good thing is with the internet now, this work goes all around the world. Anyone living anywhere in the world can immerse themselves in this culture and learn all about it. As it’s mostly a visual form, it’s easily accessible. You can just be drawn in and be amazed and get lost in these paintings. The vast majority of them are joyful and uplifting.

Pride

Indigenous art is accessible. It’s there for anyone who wants to learn about it. For these remote communities, it brings not only the ability to stand on your own two feet but it brings pride in culture. That was something that was missing in some of these remote communities. There weren’t the role models that they have now. The elders were there but people were more seduced by the western lifestyle. Now they can see there’s a strong pride and a strong draw into their own culture again. They are proud of being the oldest continuous culture on the planet. There is this depth, this complexity. These are the best placed people who really understand Australia and the land.

What Indigenous People Can Teach Us

The indigenous people of Australia have so much to teach us and they know that now. In the recent past they might have thought, “Oh, western people with their science and technology - that must be the way of the future.”

We in the west are good with material things, we’re very good. We're not so good with the spiritual. That’s where this all this art comes from. Their knowledge of the land shows through into their art. Even when they’re painting in western style indigenous people do it so well because they understand they interplay of all of nature involved in that and the Australian light and colours, the different seasons and the intrinsically spiritual nature of this ancient land. It’s all there.

Rosella Namok

Look at the work of Rosella Namok whose painting to us is contemporary, a little bit in a western style. She’s from the tropical north of Queensland. She paints the monsoonal seasons and the changes and the light and the colour, the sea, mostly seascapes or the way the sea changes, the ripples on the beach. Her paintings are so moody and evocative. Only someone who really knows the land and the seasons could do it so effortlessly and be so spot on.

Great Skill At Representing The Feel of The Land

When we had a show here by Rosella Namok, we had a Nyoongar man, an elder come up here and he said, “you could walk into those paintings”. You can feel the atmosphere of the Monsoon, all the humidity and the stillness and the calmness on the water, it’s all there. That’s a great skill to be able to do with just some acrylic and a canvas. Rosella can take you to a different part of the country and you can feel it - almost breathe in and taste and feel the humidity and the moist air.

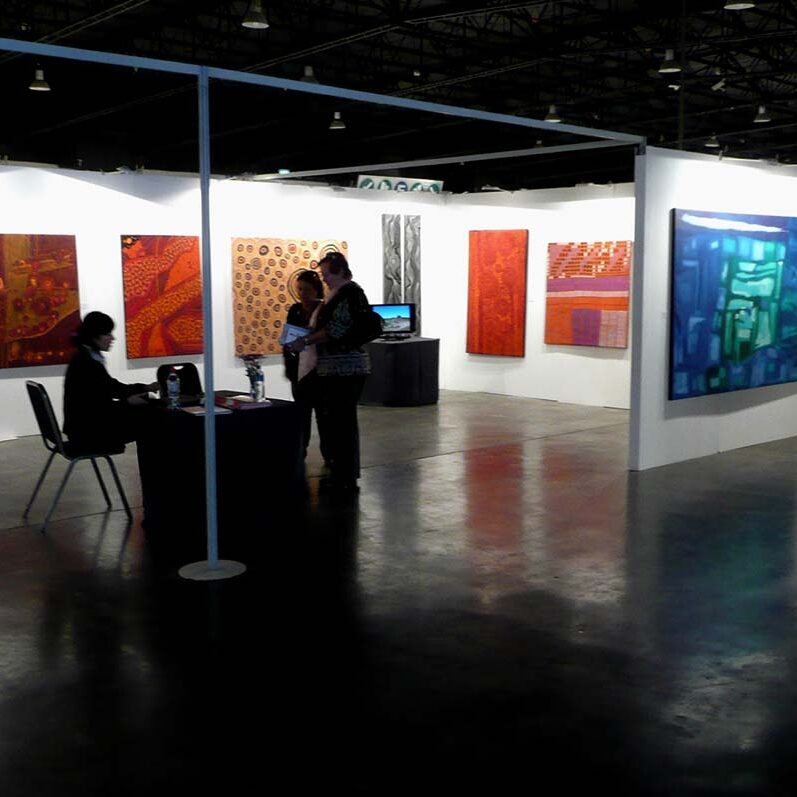

The Important Role of Art Centres

This art movement is a real privilege to be involved with it. It’s so varied. It’s so complex. It’s going from strength to strength. It can’t assist everyone in the various communities, because not everyone is an artist. But it does help keep so many strong and in touch with their heritage and culture and the benefits and positive effects are generally shared. Art centres which are indigenous owned and run are one of the major reasons that this strong art movement and the associated reconnection with culture are flourishing. From small beginnings, there are now nearly 250 Indigenous art centres in remote communities all around Australia. The art centres have provided an important focus and centre for the communities where elders, artists and young people can come together, talk about stories and culture and then paint those stories. Artworks produced in these remote areas of Australia can then appear on the other side of the planet in London, Paris and even Bucharest.

Art centres usually appoint an art centre co-ordinator who needs a wide range of skills if the community is to be successful, to remain strong and help ensure that the community realises its goals. Most art centres work in a partnership with leading galleries around Australia and all around the world to promote and present this art and culture to as wide an audience as possible. Over the decades that we have been exhibiting Indigenous fine art, Japingka Gallery has worked very successfully with many art centres and it has always been a privilege. It enables us in association with the art centre to present and promote this unique and beautiful art to appreciative audiences everywhere.

Due to their size and remoteness, even with the success and recognition that comes from unique artwork produced in art centres, most still need and rely on Government funding to survive. This is also due in part to the large amount of other important work that art centres do to keep the community and culture strong. Their main mantra is Keeping Culture Strong. They do it mostly through the interconnectedness of art, culture and the land. These elements are really indivisible but require different skills and resources. The funding remains essential in these small remote communities where often the only form of meaningful employment is associated with the art centres.

Art centres also arrange and organise trips for elders and the younger generations to go out on country to traditional lands. Often many artists don’t live right on their land anymore, due to living in a community or some of the important traditional sites are very remote. So with the help of the art centre they organise trips out there to do burning off and to perform ceremonies around waterholes and other important sites. An example of this is the Mowanjum art centre in the Kimberley where they organise journeys to the traditional remote sites. Here a senior elder will repaint the ancient and haunting Wandjina spirit figures on the rocks walls as they have done for millennia, to keep them strong and to pay respect. They sing the songs associated with each one. It’s just reinforcing those ties.

Another example is the extremely remote Spinifex Arts Project, east of Kalgoorlie with lands stretching to the now infamous Maralinga Test site. They produce powerful paintings of Country that display integrity, knowledge and inalienable ties to the land via their vibrant palettes and uplifting artworks. Japingka Gallery has been working with this art centre for around fifteen years. We have watched the art grow from art originally produced to substantiate their custodianship of the land for a successful land rights claim to joyful celebration of their ancient culture. When they have a major exhibition coming up, the artists travel out to the country that they are going to paint and camp out there and put the stories, sites and the actual land that they are camping on into the amazing canvases that they produce.

If it wasn’t for indigenous fine art and its success this process probably wouldn’t be anywhere near as strong as it is now. Who knows what would happen to these communities if there wasn’t at least some good news, in the form of something really positive happening and people from all walks of life around the world saying and reaffirming, This art is unique. We love it. We want to know and experience more. The art produced in these remote centres beautifully and so successfully introduces this remarkable, ancient culture to the world.

Read:

Wandjinas, Ochre and The Art of Mowanjum People

Everyday Spirituality: Paintings from The Spinifex Arts Project

So Much To Respect

The Australian Aboriginal culture is the oldest continuous culture on the planet. Indigenous people have survived in country we westerners would die in 4 or 5 days if we were left to our own unaided devices.

Indigenous people have been in Australia for 40,000 to 60,000 years, flourishing in this country. They had 250 different languages, nearly 600 if you can count dialects. They had strong protocols around the country, they traded with other countries and amongst one another. Art was a commodity in a certain way, it could be traded too but it was really about recording culture and making it strong. We have so much more to learn.

Thankfully the emergence of the contemporary Aboriginal art movement has helped preserve these communities, their stories and their knowledge of country for future generations and Indigenous people have been very generous in sharing much of this knowledge and understanding with us via their unique and inspiring Art.

About the Author

Ian Plunkett began marketing Aboriginal art and design in London in 1989 and is co-founder and Director at Japingka Gallery Fremantle from its inception in 1995. Ian is a founding member of the Australian Aboriginal Art Association, formerly Art Trade, and serves on the board of Indigenous Art Code, established by the Australian Federal government.

Read more: