Art Centres in Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory’s north east region is a remarkable landscape dominated by rocky outcrops and ranges that are home to some of Australia’s greatest heritage-listed Aboriginal rock art sites. These vast galleries of ochre paintings are amongst the oldest and most diverse rock art in the country, and amongst the oldest art anywhere in the world.

The Aboriginal people in north-eastern Arnhem Land are Yolngu, and the west Arnhem people identify as Bininj. There are two moieties in this region – Dhuwa and Yirritja. The majority of artworks produced in Arnhem Land are ochre paintings on bark and wood carvings, traditions that maintain direct links back to the ancient rock art of the region. Woven fibre arts such as basket and dilly bag-making and jewellery-making are also strong throughout the area.

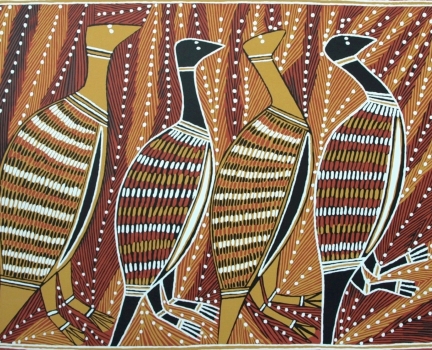

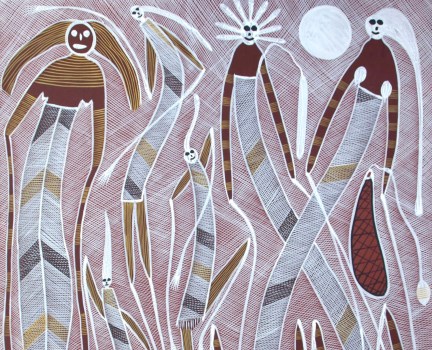

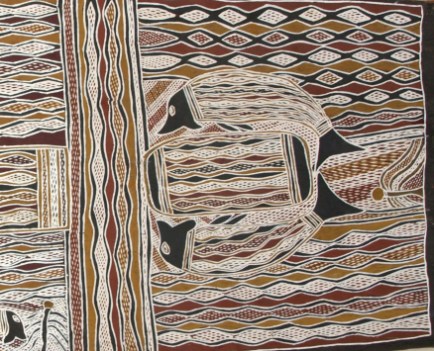

Clan and heritage rights remain central in deciding which people are allowed to paint specific stories and designs, and traditional mediums of earth pigments are preferred over modern synthetic paints. Prominent artistic forms to come out of Arnhem Land include the shimmering cross-hatching or ‘rarrk’ technique and the x-ray painting style, displaying the internal structures of the subject, as well as carved and elaborately painted burial poles, didgeridoos and hollow log coffins. There are major collections of these art forms in Australian museums and international museum collections.

About Bark Painting

The first forms of bark paintings were seen by early explorers as part of the walls of Aboriginal bark shelters. The designs were not ‘hung up’ on the walls – the bark was the wall itself. The bark paintings were not considered to be portable objects until the mid-1800s when researchers and anthropologists removed portions of the bark shelters to take back home and display as examples of ‘primitive artefacts’.

When the bark paintings were cut into rectangles in this way they resembled the canvases familiar to European art traditions, and could thus be considered as art or wall-hangings in the European context. This prompted 20th-century collectors, such as Baldwin Spencer, to commission the production of Aboriginal designs on portable, rectangular pieces of bark.

Starting in the 1930s, missionaries encouraged the production of bark paintings for sale. Their motivation was to earn money to continue running their missions. Following the 1967 Referendum, the marketing of bark painting was removed from missionaries and anthropologists by the Federal Government. In the 1970s and 1980s bark paintings began to be marketed from Arnhem Land communities as contemporary art.

To produce bark paintings, bark is carefully stripped from tree trunks after the wet season and then placed over a fire to flatten. The bark is then weighed down with stones and left in the sun for a few days. Before the surface can be painted on, it is covered with a fixative (traditionally tree sap or egg yolk). After the fixative has dried, earth-derived ochres are applied in red, yellow, black, brown and white pigments, often with a thin brush or stick.

Arnhem Land - the communities

Gunbalanya (Oenpelli)

The township of Gunbalanya (also known as Oenpelli) was initially established as a water buffalo hunting settlement in the early 1900s. Paintings were first collected from Gunbalanya in 1878, taken from bark shelters by explorers. In the following years, waves of anthropologists and collectors came through the region with great ethnographic interest in the works produced here. In 1925 an Anglican Mission was established. In 1963 the land became part of the Arnhem Land Reserve and was returned to Aboriginal control.

There are about ten language groups in Gunbalunya, the most widely spoken being Kunwinjku. A major painting theme at Gunbalunya (and in many parts of Arnhem Land) is the Kunwinjku creation story of Yingara, the Rainbow figure, and Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent. Many artists use the cross-hatching or rarrk technique to create a shimmering effect to evoke ancestral power. Animals are also frequently depicted, with careful attention to internal organs and skeletal features.

The Injalak Arts and Crafts centre was established in 1989, furthering the careers of artists such as Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek (c1926- 2009), Mick Kubarkku (c1922- 2008), Paddy Nabamdjorie Malngurra, Gabriel Maralwanga, Yumunyumun Marruwarr, Jimmy Kalarriya Namarnyilk (c1940- 2012) and Glen Namundja (b. 1963).

Milingimbi

Until the early 1900s Milingimbi Island was a trading point with Macassan visitors from eastern Indonesia, who travelled to Australia harvesting sea-cucumbers (also known as trepang). This crossover of cultures influenced the art of many communities of north-east Arnhem Land.

There are at least eight language groups on the island, divided between Yirritja and Dhuwa moieties. The island has a long history of art-making, with the earliest works collected by explorers in the 1900s. In 1923 a Methodist Mission was established, and in the 1950s missionaries began selling paintings by the Aboriginal people. In 1967 the first art centre was built.

One of the main Dhuwa creation stories depicted in the bark paintings of Milingimbi is the story of the Djang’kawu Sisters – Dhalkurrngawuy and Barradawuy. Artists from this region strictly adhere to traditional colours and patterns, the rights of which are owned by specific members of the community. Artists such as David Malangi (1927- 1999), Dawidi Djulwarak (1921- 1970), Paddy Dhathangu (c1914- 1993) and Micky Durrng (1940- 2006) are known for their figurative and abstract bark paintings and carvings.

Ramingining

The Ramingining settlement was founded after the Aboriginal Land Rights Act of 1976, which saw many Aboriginal people moving closer to their traditional country. The main language spoken in Ramingining is Djambarrpuyngu. Many artists who moved to Ramingining had formerly sold works through the art centre at Milingimbi. In 1990 the Bula’bula Arts Aboriginal Corporation was created.

Much of the Central Arnhem Land art is meticulously neat, drawn with sharp edges, and highly geometric. This style echoes the batik designs worn by eastern-Indonesian traders, and may show the influence of the Macassan people. Ramingining artist Jimmy Wululu (b. 1936) creates iconic bark paintings of diamond grids, a pattern significant to his clan. Djardi Ashley’s (c1951- 2007) work also involves refined patterned sections with repetitive geometric designs.

1988 marked the Bicentenary of Australia, with significant protest by Aboriginal people, and the creation of The Aboriginal Memorial at Ramingining. 200 hollow log coffins were created to make a statement about the deaths of Aboriginal people since European settlement, and to raise awareness of Aboriginal art, culture and history. The installation was displayed in the National Gallery of Australia and remains one of Australia’s most significant artworks.

Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island)

Elcho Island is home to more than twelve language groups – the large diversity relating to the relocation of Aboriginal clans here during World War II, and the removal of part-Aboriginal children from other areas of Australia to Elcho Island. A Methodist Mission was established here in 1942.

The presence of the Macassan people can be seen in the bark paintings produced here, with many artists drawing figurative depictions of boats. In 1957 a group of carved and painted poles were set up near the church, with one pole to represent each clan group. The poles have memorial and mourning ceremony applications and are decorated with bands of ochre pigment, woven strings and feathers.

Maningrida

Opened in 1973, Maningrida Arts & Culture is one of the largest Aboriginal art centres in Australia. Bark paintings have been sold from Maningrida since 1963, with the encouragement of missionaries. As well as bark painting, the artists of Maningrida also produce coil woven baskets, jewellery and woven dilly-bags. Some artists have produced woven sculpture and large fishing net weavings, which were exhibited at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in the 1990s.

Representations of Mimih Spirits are a common theme in the works of Arnhem Land artists, including those at Maningrida. The spirits are portrayed as very thin human-like beings.

Groote Eylandt

Groote Eylandt was another site used as a base by Macassans harvesting sea cucumbers, and Macassan boats and people are featured in a number of narrative bark paintings. On this island, Aboriginal women were fiercely protected and concealed from missionaries. An Anglican Mission was established on Groote Eylandt in 1921, and in 1938 a rival non-denominational settlement was established by Fred Gray. Gray controversially supported traditional Aboriginal ways of life on his farm, without any proferred religion, and enthusiastically encouraged the production and sale of paintings. Anindilyawaka Art Centre was established in 2005.

The predominant language on Groote Eylandt is Anindilyawaka, and the Anindilyawaka people have a very distinctive style of painting, mainly identified in the black or brown backgrounds and clearly defined imagery. Sea creatures and other animals are frequently depicted. Groote Eylandt artists painted on a range of objects including paddles and spear throwers.

Yirrkala

There are seventeen Yolngu clan groups in Yirrkala. A Methodist Mission was established in 1935, and the production of paintings for sale to museum collections was arranged soon after. These paintings became a crucial record of the Yolngu rights to the land in the 1960s when the area was threatened to be destroyed by bauxite mining. In 1963 the now famous Yirrkala Bark Petition was created in an attempt to prevent mining projects going ahead. Despite the protest being unsuccessful, this was a pivotal moment in Aboriginal history, asserting the need for Aboriginal representation in such decisions, and prompting protection of sacred sites.

In 1975 the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Arts Centre was established. In 1995 the centre presented a series of ‘big barks’ – large scale bark paintings for contemporary art galleries. Artists include Djambawa Marawili (b. 1953), Wukun Wanambi (b.1962) and Mawalan Marika (1908- 1967).

Bark Painting

This form of painting was first seen by early explorers as part of the walls of Aboriginal bark shelters. The designs were not ‘hung up’ on the walls – the bark was the wall itself.

The bark paintings were not considered to be portable objects until the mid-1800s when researchers and anthropologists removed portions of the bark shelters to take back home and display as examples of ‘primitive artefacts’. When the bark paintings were cut into rectangles in this way they resembled the canvases familiar to European art traditions, and could thus be considered as ‘art’ or ‘wall-hangings’ in the European context. This prompted 20th-century collectors (such as Baldwin Spencer) to commission the production of Aboriginal designs on portable, rectangular pieces of bark. Spencer would pay the artists with tobacco.

Starting in the 1930s, missionaries encouraged the production of bark paintings for sale. Their motivation was to earn money to continue running their missions. Following the 1967 Referendum, the marketing of bark painting was removed from missionaries and anthropologists by the Federal Government. In the 1970s and 1980s bark paintings began to be marketed as contemporary art.

To produce bark paintings, bark is carefully stripped from tree trunks after the wet season and then placed over a fire to flatten. The bark is then weighed down with stones and left in the sun for a few days. Before the surface can be painted on, it is covered with a fixative (traditionally tree sap or egg yolk). After the fixative has dried, earth-derived ochres are applied in red, yellow, black, brown and white pigments, often with a thin brush or stick.

Read More:

Australian Aboriginal Ochre Painting

View More:

Hamish Garrgarrku

Edward Blitner – Stories from my Grandfather