Jimmy Pike – Remembering His Life & His Art

By: David Wroth, Japingka Gallery, 2017

In this article Japingka’s David Wroth discusses his experience working with Jimmy Pike, commencing at Fremantle Prison during the early 1980’s. After Jimmy left prison they continued to work together through the marketing of Jimmy’s work with Desert Designs. David talks about Jimmy’s working process and the elements that you’ll see in his work.

Jimmy was one of the students in the school in Fremantle Prison in early 1980’s. I met him in 1983. He was a very traditional man who was in prison for a serious offence. I was a part-time tutor in the school at Fremantle Prison doing printmaking. I thought lino-carving would be one of the things that would be easy to do.

I took in the various lino-carving tools and the print-blocks. Jimmy Pike was one of the students. He said “Oh listen, can I take it back to the cell. I think I want to do it there.” I thought that sounded fine. I gave him three lino-blocks to take back to his cell. I suppose the school in some ways was a little bit intimidating for traditional people. I’m not sure. There was often a lot of Aboriginal people in the art group but some aspect of it, maybe revealing something of traditional culture, wasn’t working for him. When I think about what came next, I see the logic of it.

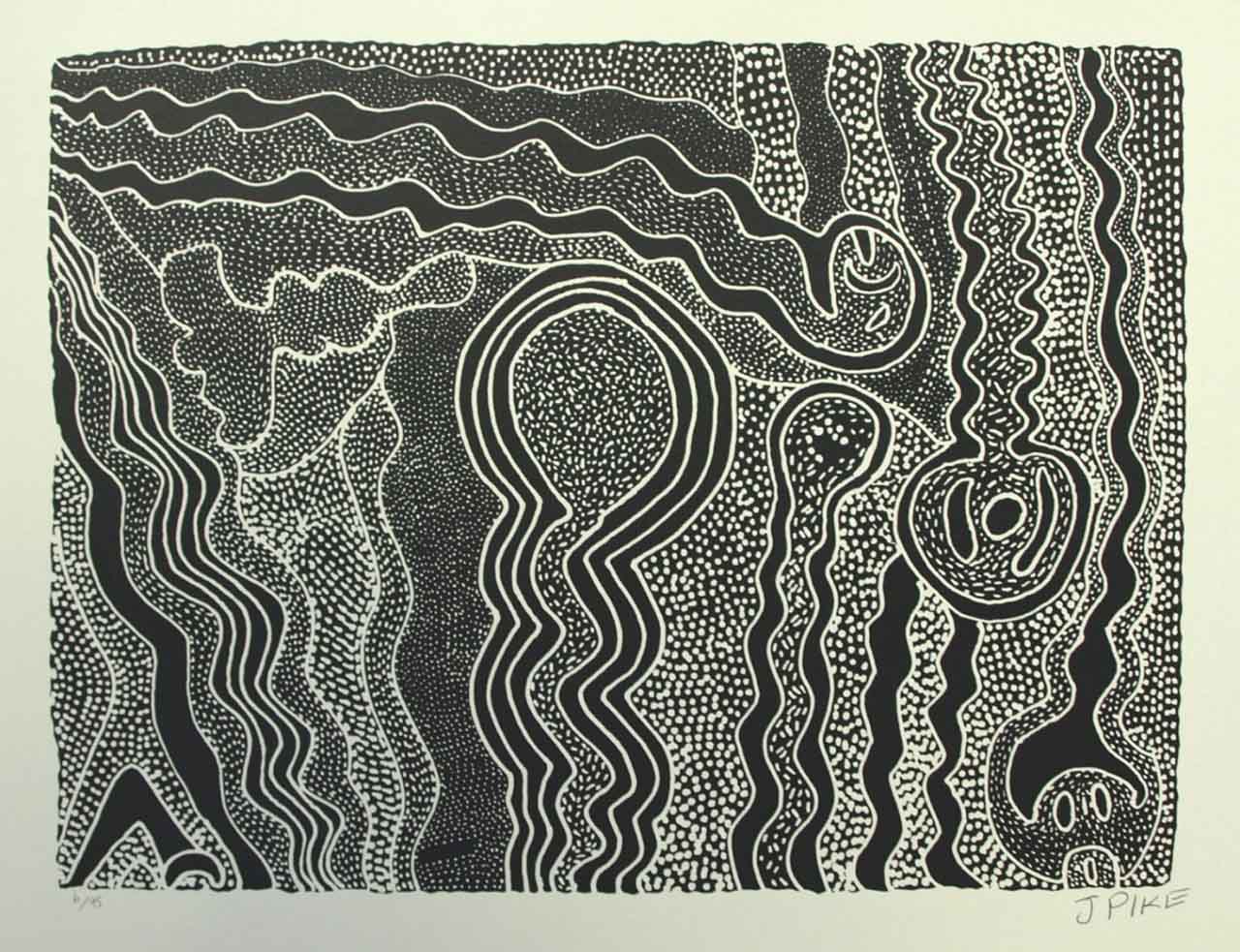

I came back to Fremantle Prison the next week. Jimmy came down and he had carved three of these lino-blocks using ordinary lino tools. He created three sensational images. You could just look at them and go “Wow, Okay.” The imagery, the kind of graphic quality of them was impressive.

One of the images was the main waterhole from the country Jimmy came from. It is called Japingka. There were six circles that looked like wagon wheels and they were the various sites where the water was feeding into this waterhole. This turned out to be the main ceremonial place for all of his people, so it’s where everybody came together. It had ceremonial importance and social importance, it was just like a cultural hotspot for Walmajarri people.

The other image was one of a figure rising up out of a waterhole. It had electric hair, it was a head with sharply radiating lines coming out of it. Again you could just feel the energy of the rainbow serpent or the water-snake image coming out of that same waterhole.

The third carving was another location in the desert where he was from. The three of them were just knockout images. This man had never carved a lino-block and didn’t need to understand the principles of a lino-block. I had briefly said, “This is how it works.” I had to show him.

For Jimmy, it was just a carving and it was just like all the other carvings that his people did. He would have carved at home and his people were very familiar with working in that way. They would have been carving very important designs onto ceremonial items or artefacts. If it was important enough to carve a design on it, you carved something that was significant because that was the carrying force.

Jimmy’s early works for prints were all black and white and he did a whole series. He did twenty-five of these lino-blocks and the majority of them were really intriguing, though some were not as complex as these early ones.

One of the interesting things is the carving techniques used by Aboriginal people. The whole use of tools is different to Western use. The normal way for an Aboriginal person to carve into wood or on a boab nut is a kind of wavering motion with the hand. The tool makes a zig-zag, it moves forward and makes this energetic line. Jimmy’s carving on lino-block rarely has the smooth lines that we might expect with non-Indigenous lino-block printing. It’s all got this kind of energetic waving line that’s full of jagged edges.

Jimmy’s approach to lino-carving is exactly the technique you see people using in traditional community settings. They use a pocket knife and you see people carving Boab nuts or sometimes carving onto wooden artefacts if they haven’t got a chisel. They’re using the point of the knife and they’re moving it along by wavering it back and forward. It moves in a kind of a serpentine way. And it gives this really energetic, quite electric sort of line.

Jimmy Pike had an interesting approach to style because although initially, the images were quite symbolic, using the symbols of desert art, he was also very perceptive as a figurative artist. At one time his work may be composed of symbols, which were very two dimensional, and then at other times, he would use figures and sometimes incorporate them into abstract designs.

Sometimes he would paint in a landscape style that would have the horizon and vertical perspective. He was not fixed as to the type of images that he used. He might make a figure, sometimes a Creation Ancestor, and it will be surrounded by all the images of the desert. It is sand hill country, that traditional country. He employed quite graphic images and then surrounded them with types of designs that represent sand hills in his country.

Jimmy Pike didn’t talk much to me about his art during that time in prison. I was only involved in the printmaking, and the school ran other art classes at the time. What I found was that when you work with Aboriginal artists it’s rarely been easy to talk about conceptual ideas – design, stylistic approaches and techniques.

Aboriginal people learn by watching. That’s how it’s passed on down the generations. The idea of actually talking about abstract things with Aboriginal people I found very difficult. There’s no point. They just need to see someone who is good at it doing it and then they’ll pick it up very, very quickly. It’ll save thousands of words that don’t achieve much.

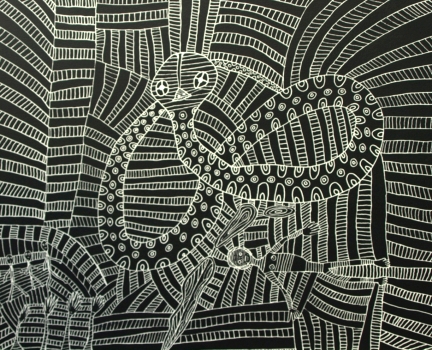

Man in the Desert

All the vertical lines around the figure might at first seem like a prison reference. It isn’t. It’s like a maze and it’s quite interesting. The figure inside a maze-like pattern, this is actually an ancestor journeying across the country and the lines just represent the sandhill country. It has a three-dimensional quality to it.

Later we started to see more of this type of imagery in Aboriginal art from the Western desert, from Kintore and Kiwirrkura. It started to emerge in the decade after this image was created. It’s shared imagery, it’s shared understanding of what that represents, it represents desert country, it’s not to do with Fremantle Prison and it’s not just any place, it’s quite specific.

The starting point for Jimmy Pike to create prints was working with lino printmaking, but it didn’t end there. Jimmy Pike loved colour and he was a very direct artist. He would just tell a story very directly in his imagery. He loved texta colours, so he drew all the time using texta pens. The original images were created using texta colours and they came in sets. I think there were ten colours and you got a bright pink, a purple and a blue, a black and brown, and you got two greens and an orange and reds. That’s exactly what he used, just those colours. The whole compositions were made with colours straight out of a little ready-made set of these ink pens. He worked his way through boxes and boxes of those little sets.

It wasn’t sophisticated material, but he was actually more interested in the kind of energy of the thing that he as drawing, or the power. Quite often he would represent the power of a place by creating an aura coming from it, or the bands of power coming out of the site, and he would use colour to reinforce that feeling.

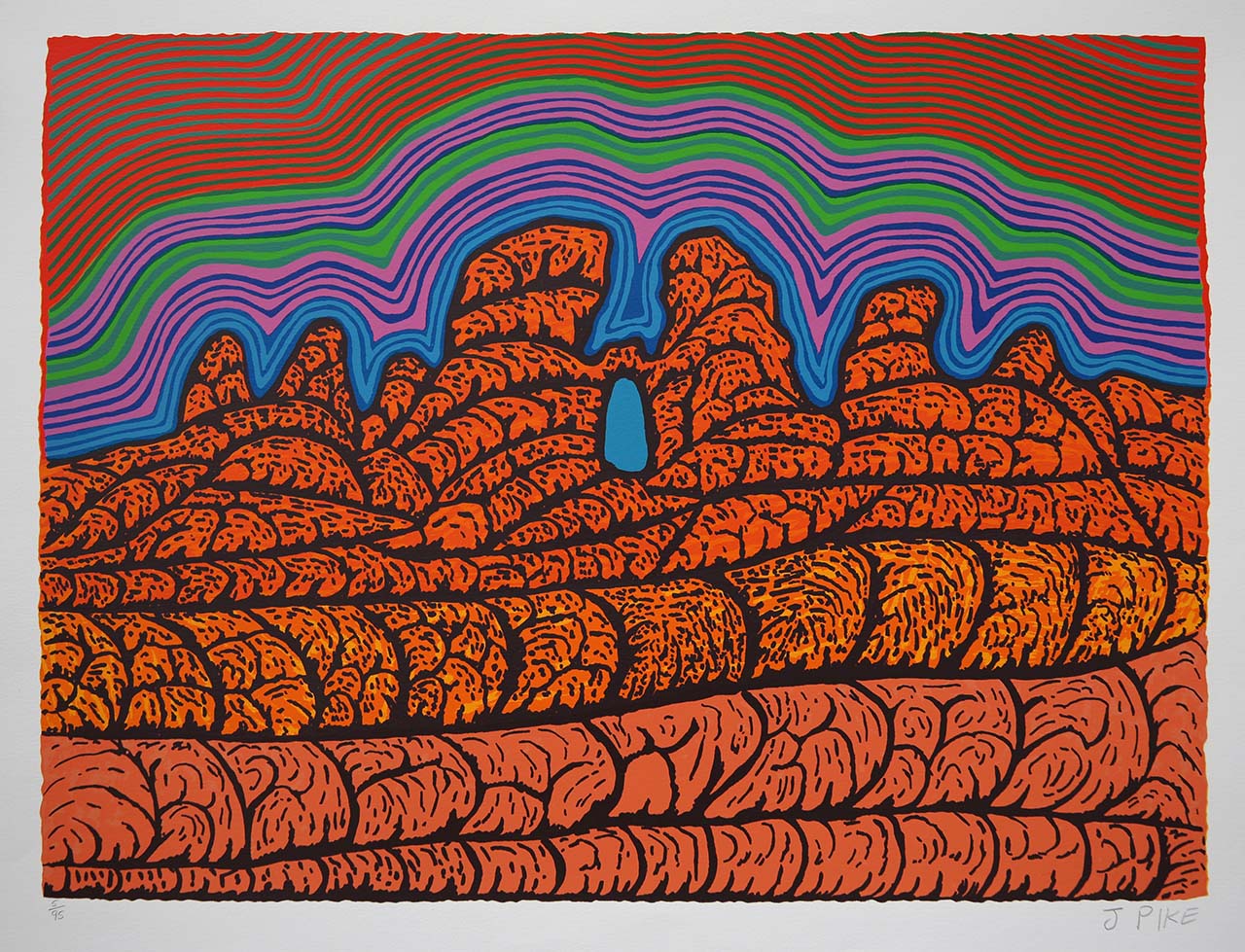

Waterhole

You’ll see in the images of the Japingka waterhole that you’ve got the sources of the water. This is all done with texta colour. The strength of colour tells you this is a highly significant place for the artist and it’s got all the sandhills that enclose this location.

The colours selected are not fixed in their connection to the meaning of the image. He was just using the whole set of colours that he had available to create the most energy. His major focus was on the sense of drama and the importance of the site that he was painting. It didn’t matter whether it was a landscape, or a set of symbols representing a place, or a figure that represented a Creation Ancestor.

I think Jimmy was carefully looking at colour and creating a composition that suggests that there’s something powerful happening in the centre of the waterhole. You then see the country, the sandhills and there’s other little supplementary water places. This is the geography, the terrain. This artwork reminds me of one of those geophysical maps that go from red to green and represents either the altitude or the intensity of the conditions it’s measuring. For me this is measuring the spiritual heat of this site, you see it radiating out.

This type of artwork was originally done in texta pen. A professional printmaker then went through with transparencies and separated out the colours. Jimmy later signed the print edition as his original work.

I would describe Jimmy Pike as a figurative artist. When I say figurative I mean that his work is representing either a person, or an animal – or the spirit of a person, or the spirit of an animal. And also spirit figures are seen as Creation Ancestors. There is the shape of a recognisable person or a representation from nature at the centre of these artworks.

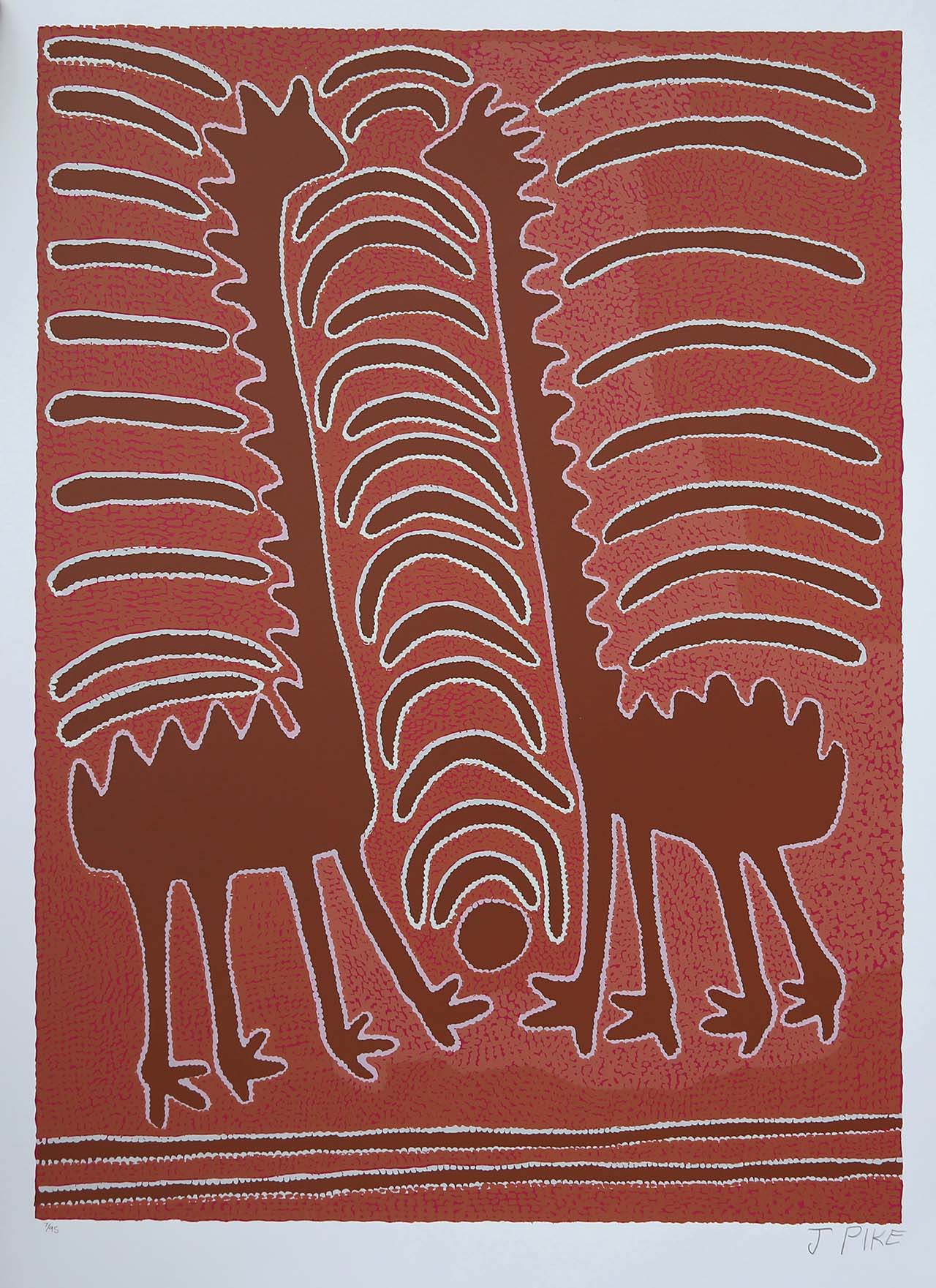

Kalpurtu Water SpiritThis is another interpretation of the Rainbow serpent or the water spirit. These are somewhere between a spirit figure and a pterodactyl from the dinosaur age. It is the whole idea that there are ancient spirits embedded in water holes. This is quite an extraordinary sort of image.

At one level it could be part-emu crossed with a camel, crossed with something else. It’s got a bird’s feet, it’s got the serrated back of a prehistoric animal with a long neck.

One of the things that I found amazing about Jimmy Pike is that he was giving shape to ideas in a figurative, artistic way that maybe no one else had delineated. I’m wondering whether there were many different forms for how the Water Spirit was. It may well be that the Water Spirit existed in ceremony and it existed in song, but you don’t see it in rock paintings and who knows whether it was represented in other forms such as sand paintings. I suspect it’s probably very unlikely. I think with Pike’s work there’s an artist-creator’s imagination interacting with the whole song cycle and ceremonies about the Water Spirit. He put shape to them, and they’re all quite different to each other. Some are looking like imaginary beasts and others are looking more like what we might expect from a Rainbow spirit image.

A Rainbow Spirit or a Rainbow Serpent or a Water Snake – these are the big connecting forces between all the water resources in the country and move with the rainstorms that come in from the coast and go deep into the desert. It has that sort of rainbow attachment, it can either move in the rain clouds or it can move underground between the water resources. It’s a very significant story in traditional culture.

Jimmy Pike would say that they had a whole language that was ceremonial language, and it was a deep and serious language, and it was different to the everyday language that people would talk about ordinary everyday things. So it was quite an education to tease out the stories. In many ways, the paintings tell the story best. You see the Water Snake with the rainbow shape streaming back from him. There’s the water underneath containing the bands of contrasting colour. Above there’s a slipstream that talks about the rainbow and the water and the movement from one location to another. Again that kind of aura, the way he creates, using colour in line with bands of contrasting colour. He creates auras around the things that tell you that they are big and significant forces to him.

I believe this work was Jimmy’s escape from his immediate reality. He’s in prison for something like six to seven years. The things that he’s connected to are these very traditional stories and locations. He was three and a half thousand kilometres away from his country, but his art was keeping him sane. The culture is feeding his imagination and it’s feeding his artwork.

Jimmy hadn’t really done much art prior to this time in prison. He had certainly been a carver as many people were, so he was very adept. When he left Fremantle Prison he said: “I like this job of being an artist and I want to be able to do it when I go back to my country.”

He was in his late thirties when he went to Fremantle prison. So he was in his early forties probably, when I met him. He had already been in the art classes run by Steve Culley for at least two years, so he had been through the process of learning particularly about paint and painting with gouache. The texta colour thing, the whole use of colour was something that he found fairly early on in his career.

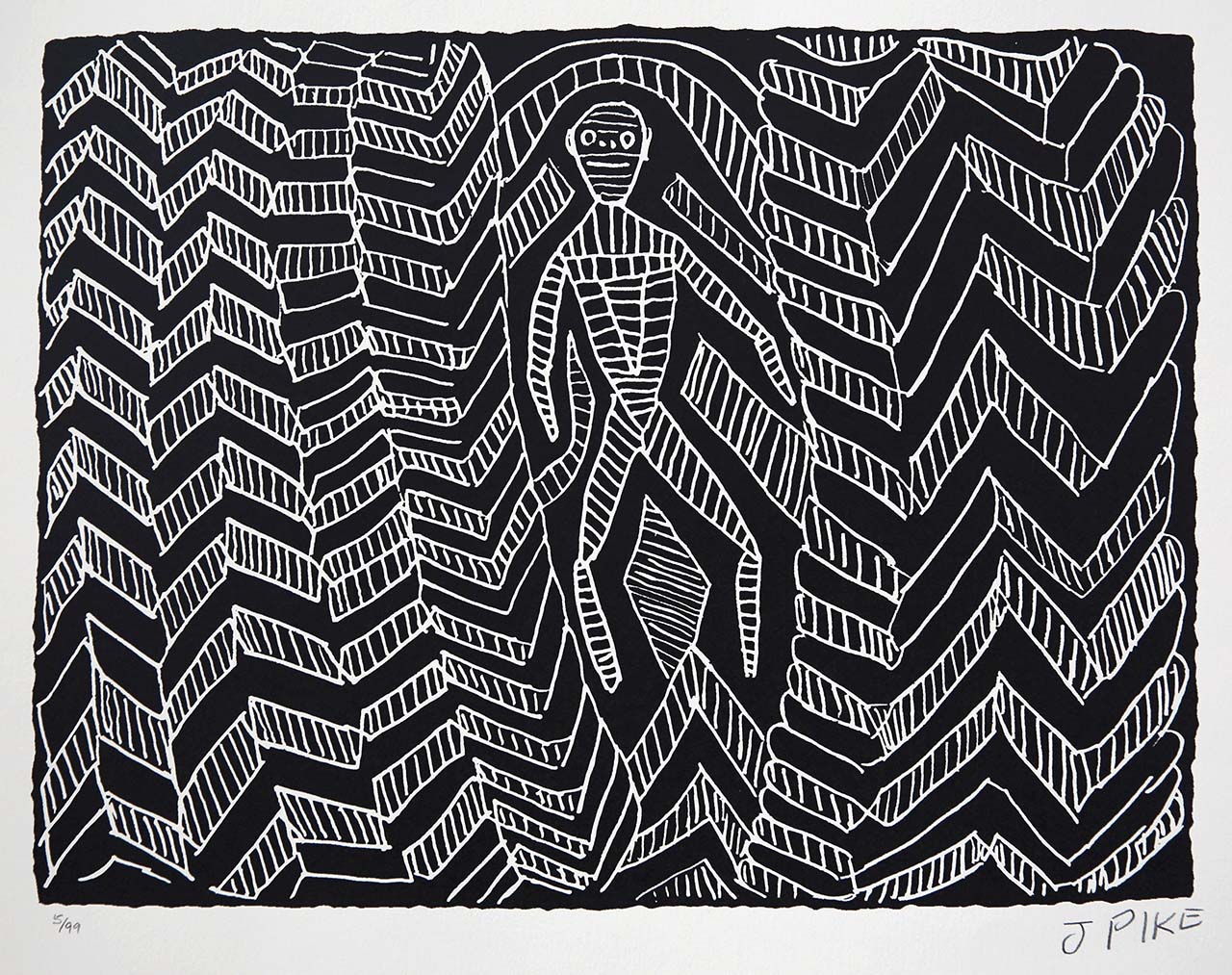

Two Men Sleeping by Two Fires

This is a black and white design Jimmy Pike described as a brand. In retrospect, I think he was referring to the branding of cattle. To him, it was a symbol, that when you saw this it came from the part of the country in Australia that he came from. If you saw it on an artefact and if the artefact had travelled 3000 kilometres it wouldn’t matter, it had the brand of his country on it, and so he used the word brand as a kind of identifying symbol that connected something to its place of origin.

Jimmy often talked about the desert having, he would call them Kurrkuminti, which are the hollow spaces created by high sandhills. They were protected locations. The desert sandhills are substantial. They are often more than four or five metres high and they’re in parallel rows about 200 metres to 500 metres apart. So Kurrkuminti were shelters, they were protected from the wind. They’re much warmer in the cold winter nights and so people valued these locations. They also protected animals and plants. They’re most like a hidden valley in sandhills. So if you’re in a maze of sandhills, this kind of knowledge of Kurrkuminti is very important to have. So that image is contained in the carving of the brand.

The water holes dried up at certain times of year, and most of them were connected to water below the surface. The big problem was they could get buried in sand drifts. The water stayed in one location, but it was buried if nobody was there to dig them out. After three months there could be a lot of sand filling them in. And when Jimmy’s people re-visited some of these waterholes after 30 or 40 years, they had to dig them out with shovels, and they were digging one-and-a-half times the height of a person down to the ground. So they were like little wells. They literally dug the wells and then went down inside and scooped it out till the water started to flow in. They knew the water was there. They found water two metres, three metres underground. They knew where it was because the knowledge was in the stories and songs and in their own memories, and they dug it out with shovels and with large tin buckets.

Some very iconic images that Jimmy Pike made are of Japingka waterhole, and this is another one. You’ll see the circles, the different springs or feeder sources of water. Japingka waterhole in the middle and there’s a protective hill or rock at the back of the site.

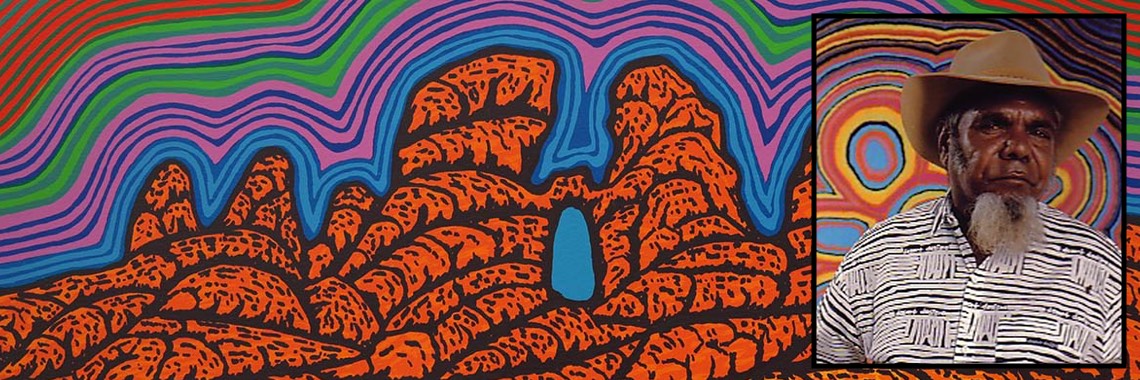

Kurriny Piyirnkujarrra

This is another example, call this a landscape, there’s a blue sky and there are red and orange rocks and what looks like a cliff face. It’s a location that Jimmy Pike described, it’s actually a hole in a cliff face.

So there’s an open gap in the rocks and you can see straight through it. So the image feels a bit like a waterhole, with the sky above. But it’s actually a location where a Creation Ancestor looked through the rocks, and where he looked though has become a permanent portal right through the rock. But it’s a good example of the style of landscape that Jimmy Pike would paint. This is originally created with texta pen. Some of the colours appear to be blended tones. I think he’s been able to blend, by working almost quickly with wet on wet before the texta ink is dry. He’s been dragging the brown and the orange colours across each other. The paper was not fantastic paper, it was just litho paper. It was a very smooth surface, quite a glossy surface. That meant that he could blend colours a little before they dried.

He also used a black texta pen which wasn’t in the colour set. It was a standard black marker pen. He’s created all this other texture on top over the colour of the rocks, and then the sky’s got these two tones of purple and blue.

Jimmy did say at one time to his non-Aboriginal wife Pat Lowe “We’ve been here before, I don’t understand why you can’t recognise the country” and Pat said, “It looked like desert to me.” It was an open space, it had trees and stones. He was recognising all the markings and all the location signs and to someone who’s not familiar with that country, they weren’t recognising this at all.

Jimmy Pike was pretty excited about seeing the range of his work coming out to be seen by a wider audience. He was very matter-of-fact in a way. On one level he said “I like this job of being an artist and I want to do it when I leave prison” he also said things like “We’ll put the prices low so they’ll buy ’em and when they really like ’em we’ll put the prices up.” He was a very honest, a very practical person.

There was another artist in the aboriginal group in Fremantle prison, a man called Martin Dougal. If you asked him to put a price on a painting he would say “Oh that’s a really important place, that’s worth three times as much as that other place because that’s not so important.” So he was actually thinking in a completely different way, not an artistic way, not a marketing way, he was just saying “Well that’s an important place so it’s going to be three times as much.

Rainbow Serpent

Some of these texta colour drawings were also done after Jimmy Pike had left prison. This one is done later. Pat and I think that this may well have been influenced by the Shinju Matsuri festival in Broome. So Jimmy Pike’s still drawing the Water Snake or the Rainbow Serpent, and all the imagery suggests that it’s a Water spirit of some sort, but it’s kind of Asian feel to it.

Jimmy had gone back to the Kimberley, back to Broome. This may be a great cross-cultural image created by an Aboriginal man. This particular face does appear on another Water snake image, and I think it actually represents Jimmy Pike’s face. You can see his beard, his mouth, large eyes. Jimmy Pike had quite a round face.

This face strongly reminds me of somebody reflecting their own face on to a spirit figure. The same face does appear in a few other drawings, not a lot, but a few. The interesting thing is they’re all quite significant things that the face appears on. There’s a close idea of connection between the artist and the subject.

Rain

Not all of Jimmy’s work is in ink, and this was originally painted using gouache – poster colours in little jars, painted on paper. It does represent Japingka, the waterhole. This picks up another part of the story where traditionally the people would sing up the rain from its location. They would gather there but all the song people would sit around the water hole and they would sing up the rain. Jimmy said that the clouds would form above the waterhole.

So we’ve got the bands of cloud that come ahead of the rain storms in the desert, the little strata clouds. Then you get the larger ones and then you get the big rain bearing clouds. He’s represented the waterhole, he said the singers are in here, the ceremonial singers are singing up the rain, the clouds are starting to form, and he’s saying the clouds also form the sandhills. There’s this kind of merging between the symbolic clouds surrounding the waterhole, then there are sandhills, which are kind of morphed out of the design that represents the clouds and then there’s the green of the country, so these trees and shrubs. There are these lines emanating out from the water holes as though it’s the centre of the universe. I think that when everyone is there performing the rain ceremonies, it’s very much the focus of the universe.

Early Years

Jimmy was a bit of an outsider with a very strong traditional connection. Their particular situation was interesting because he walked out of the desert when he was maybe six or seven. They survived off the land. It was the 1940’s and his people were leaving the desert and moving up into the Kimberley cattle station areas. Very significant people were leaving the country and taking their knowledge with them and going to live along the banks of the Fitzroy River.

This was during the war. Jimmy Pike’s got images of bombs being dropped in the desert from the war-era and they are from his childhood. And so I think during the war and post-war period, that emigration process was happening really strongly in his part of the country. In other parts of the desert it happened earlier, other parts it happened later.

The 1940’s were significant because it was a very bad drought time in the desert and people were forced to make decisions about what they were going to do. A certain number of people left the desert. It became very difficult to maintain the water holes because they said you needed six people to dig out some of those big water holes because the sand you dug out could flow back in, so you needed a lot of people working to get to that point where you hit the water and the sand movement was stabilised.

Law and Culture

In terms of whether Jimmy Pike did have a significant cultural role, it is complex. Like many others, Jimmy worked as a stockman and general worker in the pastoral industry in the Kimberley. And during the rainy season, this was when people held ceremonies on his country and in the new Kimberley settlements. Of necessity the people they had to spread out in the dry season, break into smaller groups and go hunting in different areas.

Later on, the ceremonies were still held at the same time, the Wet season, but they were held in particular parts of the Fitzroy Valley. Everyone would still come together, and they’d come from literally hundreds of kilometres away.

Walmajarri people had settled from Halls Creek to Fitzroy Crossing to the coast south of Broome – working on cattle stations or settlements or in missions. Jimmy’s people had really diversified into different parts of the Kimberley but they would come together for ceremonies.

There is the sense that the important Law people were still the cultural authorities even decades after moving to the Fitzroy Valley. It became more broken up over time with people working in different areas coming together just for one month of the year. The cattle stations used to close down during the rainy season because the cattle couldn’t move and it was too wet for machinery, trucks and tractors. It was a good time for Aboriginal people to be carrying out ceremonial and social duties.

Conclusion

Jimmy Pike had a powerful influence over the use of bright colours in contemporary Australian Aboriginal art. His commercial success was an early sign for Aboriginal communities that their art could lead to a sustainable income.

The success of his artwork represented an important step in the recognition of traditional cultural imagery within mainstream Australia.

Read more: