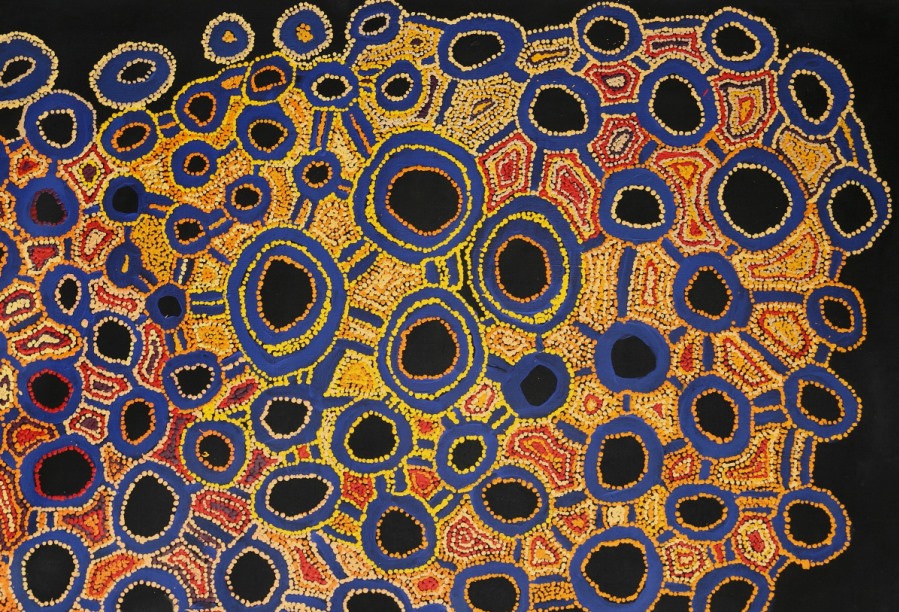

Water in Aboriginal Art – the Centre of Life

One of the great recurring stories in Aboriginal art is the location and presence of water on traditional lands. Over the vast land mass of the Australian continent, much of the country is in dry and water-deprived condition for large parts of the year. Throughout the different climate zones of the continent, the presence of water plays out in different ways, and this is possibly most obvious in the desert regions.

Aboriginal ownership of land centres on clan estates, also called traditional lands, which are inherited down family lines. This means family groups have a traditional access to a tract of land, which they travel across in a seasonal journey following the availability of food and water resources.

Knowledge of water is critical in this process. It defines where the animals will be found and how the native plants will flower and bear fruit and nuts that are then gathered by Aboriginal people. By knowing the location and condition of local water sources, Aboriginal families reinforce their ownership of their traditional lands.

Walmajarri artist Jimmy Pike from the Great Sandy Desert, addressed the ownership of land and the idea of Crown Land in this way – if Crown land belongs to the government and ultimately to the Crown (the representative of the Queen of England), then those people must know where the water is. But if they came out to this country they wouldn’t know where the water is to be found. So their claim that this is Crown Land is wrong, because it is based on a false premise. Owners of land know where to find the water.

Water is mostly found below ground in the desert. Any surface water quickly dries up in the heat, but underground water remains available in waterholes and rockholes.

Aboriginal people of the inland differentiate between permanent water, called Living water, and seasonal water that dries up during parts of the year. For Walmajarri people like Jimmy Pike, the word for permanent water is Jila, whereas the word for seasonal water is Jumu. Knowing the difference between these sites and the amount and quality of the water found there is critical to survival and to the management of the land generally.

Desert waterholes are subject to being buried over by moving sands, and need to be maintained. Some waterholes require a certain number of people to dig them out, as the sand tends to slide back into the well as it is being dug out. As the number of Aboriginal people living in the desert declined over time, and as people left their traditional lands, many desert waterholes were buried by sand and largely forgotten about. Knowledge of their whereabouts remains with the traditional owners, and is often recorded in their paintings. The loss of these waterholes has also affected the populations of animals, which cannot access the water without the help of human intervention.

The Spinifex people who live in the Great Victoria Desert in the south-east corner of Western Australia have been revisiting waterholes that they knew when they were children, over 50 or 60 years ago. Many of these waterholes had not been visited since that time. The plan is to locate and map these ancient sites, and record them using a GPS location. As adults the people were able to re-trace the locations of small waterholes in the desert, based on their own memories from long ago. Once they could locate the waterholes, the modern technology provided a GPS location, so now the position of waterholes will be recorded, even after the old people whose families lived there for thousands of years, may have passed on.

Water is at the centre of knowledge of the land, and much of the ceremony and culture of Aboriginal Australia is focussed around the locations of water, which are also linked to important ceremonial sites.

Read more: