The Early Influence of Geoffrey Bardon on Aboriginal Art

Papunya and Geoffrey Bardon

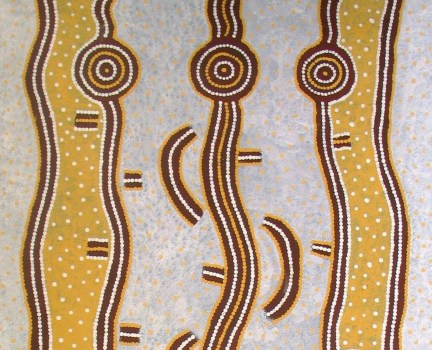

If you are new to aboriginal art you may not have heard the story about Papunya and Geoffrey Bardon. This is a powerful story about a courageous displaced people and a man who worked against enormous pressure to bring their culture out into Western view. Bardon’s vision and courage came at a critical time and provided an initial spark to bring into the light the early works of pioneer painters from this extraordinary art movement.

This story starts in an Australian outback government town of Papunya. It was home to many different groups of desert aboriginal people, including Pintupi, Luritja, Walpiri, Arrernte, and Anmatyerre, who’d been moved there in the late 1960s under a government policy of assimilation.

The town had no cultural significance for the people of these different language groups. Many of them had, up until this time, lived on their own country with their own language and followed their traditional ways. They all had rich story telling traditions that related to their ancestral country. Now they found themselves separated from the very country that had such significance for them. It must have been a truly devastating time.

It’s The Old People Who Know

In 1971 Geoffrey Bardon came to Papunya as a school teacher. He asked young school children to paint things that related to their world, not to the western ways. Eventually the older men who spoke some English came to him and said, “Why are you asking the young people? It’s the old people who know.”

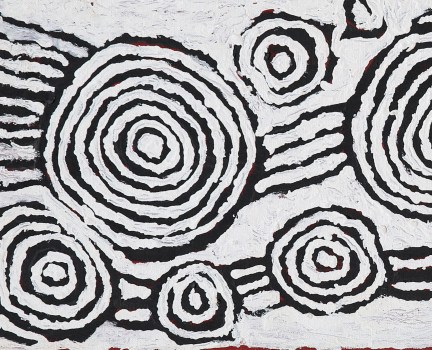

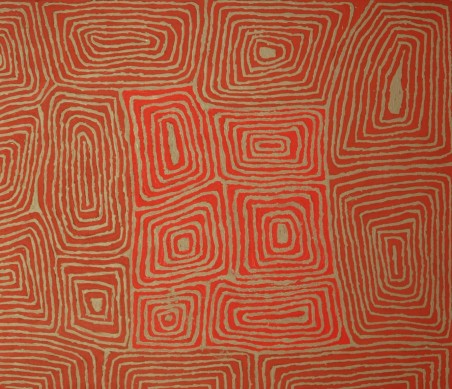

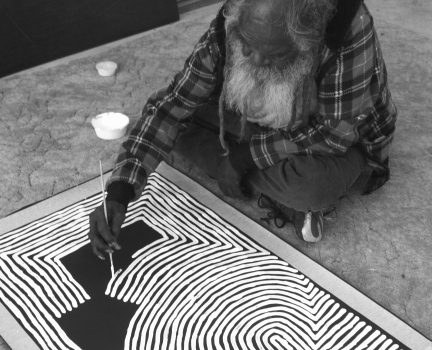

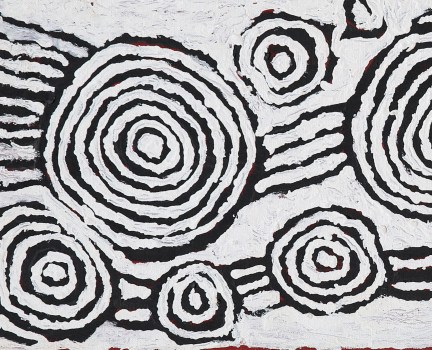

A group of men started telling very significant stories. This meant they had to work out which aspects of those stories could be told and which parts had to be withheld from public view. The men from at least half a dozen different language groups worked on this together. They worked out jointly how they could express very significant aboriginal stories without upsetting the requirement for non-initiated people not to have access to the meanings. Once this was resolved it meant that the elders could paint their stories. In these early stages the pioneer painters were all men. Bardon arranged for them to paint a mural. He then started supplying artist’s paints and canvas. In 1972 he arranged a painting area in the storeroom of the Town Hall hut. There are 23 artists recorded as belonging to this first generation of Papunya Tula artists.

Against The Grain

In showing interest and nurturing visual representation of aboriginal culture, Bardon was working against the grain. He was encouraging aboriginal artists at a time when the administrators were against providing financial support for an art business. They did not want to provide infrastructure to support any activity that promoted traditional values. If anything they wanted the aboriginal people to let go of their traditional beliefs and embrace the Western culture. Bardon’s interest in traditional stories and visual recording of those stories was met with indifference and hostility from the town administration.

Despite the lack of enthusiasm from the town administration, Bardon was able to supply basic art materials to a group of elders and they painted their stories. There was no support for his attempt to market these early art works or to involve the aboriginal people in the wider commercial art world. The administrators of the day just saw it as inappropriate. That was a whole political and bureaucratic sensibility from that era that had carried on for a long time. It must have been a highly stressful time for Bardon to take on the role he did. His actions were critical in encouraging and bringing out the art of that time.

Allies

The personal stories we’ve heard from people who knew him was that he would ring up all his contacts and say “we are bringing in a bunch of paintings into Alice Springs, get here and buy some of them”. He was desperate to succeed. He didn’t want to let the artists down. If he failed, he felt the message that would go back that people were not interested in the paintings. He risked a great deal by doing what he did.

He was a hero of the movement I think. Aboriginal artists needed a really good ally. They needed someone to side with them. They’ve always had people who have done that. But in this case, for the artists at Papunya, when they needed someone, Bardon risked a lot to support them. He probably risked everything from his career to his own well-being to achieve that.

Successive people have come in and supported further work and carried the extension of those programs into other communities. Obviously, they were in the main, arts people who both valued the art and wanted to see the movement succeed.

What you can’t over-emphasise is that it’s the Aboriginal artists who are the heart and soul of that early Western Desert art movement. In those early days they also needed someone to be their ally and to make it happen. Many aboriginal people have strong personal connections with people that they’ve worked with and who can make those sorts of things happen in their life-time.

Aboriginal art as universal language

I think we’ll look back and see that the timing of the evolution of this modern art movement was critical because there were mostly people who had lived a traditional lifestyle and were now living in Papunya. Painting, by virtue of it being a universal language, overcame a lot of the problems that we had in understanding something about aboriginal culture. The language difference had been a big barrier because there were so many aboriginal languages. Except for a few anthropologists, missionaries and educators, most people had no real capacity with aboriginal language. Therefore, the song cycles, the music, the stories were difficult to comprehend except for those anthropologists that collected them, but they never would have gained a wider audience.

The art movement coincided with the availability of acrylic paints which become more widely used within the art world in the 1970s. That also coincides with the emergence of this modern movement. Art advisers started wanting to see aboriginal values and stories expressed in art. They provided good quality, long-lasting materials. This happened in combination with people being encouraged to tell their cultural stories and those custodians making the decision that it was appropriate to tell those important stories.

The availability of good quality materials came at the same time as the availability of interested people who wanted to know about culture rather than trying to suppress it. All those things came together to make the art the most visible and wide spread expression of aboriginal culture to non-aboriginal people.

Since then there’ve been some wonderful theatre productions that have given us insight and there has been some marvelous aboriginal bands and groups that have expressed aboriginal values. I think it was the painting that came first and opened up the other possibilities. I think this is even true for the films that followed.

Cutting through attitudes

I think aboriginal art had to cut through not just the lack of knowledge. It also had to cut through the attitude that aboriginal culture didn’t have anything to contribute to modern day Australia. Once the art had disproved that attitude, then I think the possibilities were open for other aboriginal art forms to gain wider acceptance. I think that the art worked very much as a door opener. It’s an ambassador first of all for aboriginal culture and then it becomes an ambassador for wider Australia. It’s made that enormous step from being an expression of an aboriginal experience to being a statement about the uniqueness of Australia, expressed by aboriginal people about language and about culture and about landscape. Certainly Australians can accept it as a statement that is from an aboriginal point of view. Perhaps that says something about the landscape that is Australia, and that we are all now very much feel attuned to.

The influence of the Aboriginal art movement

The aboriginal art movement has influenced how all Australian’s relate to the land, to the outback – to what is unique about the Australian landscape. It has helped lead Australia away from the European filter through which so many white Australians viewed this country. These days it’s possible to hear people, when they are buying Aboriginal art, say that it is because it reminds them of what is unique about Australia, and that it captures their own love of the outback landscape. I think it was aboriginal art that reinforced the idea that the Australian landscape can be experienced as something spiritual and sacred, and that is significant on many levels.

The story of the pioneering artists of Papunya and Geoffrey Bardon is inspiring and worth retelling. It was not only the start of an art movement but it is also evidence that the actions of individuals can have great consequence.

This story tells us that even in the most overwhelming circumstances it is worth taking small steps toward what is authentic and just. This is as true today as it was when Bardon took up that teaching post at Papunya.

______________

Related Collections & Exhibitions