Zenadh Kes - Art of the Torres Strait

Gallery 1

31 May 2013 - 10 July 2013

Extract from essay by Simon Wright, Director, DELL Gallery, Queensland College of Art

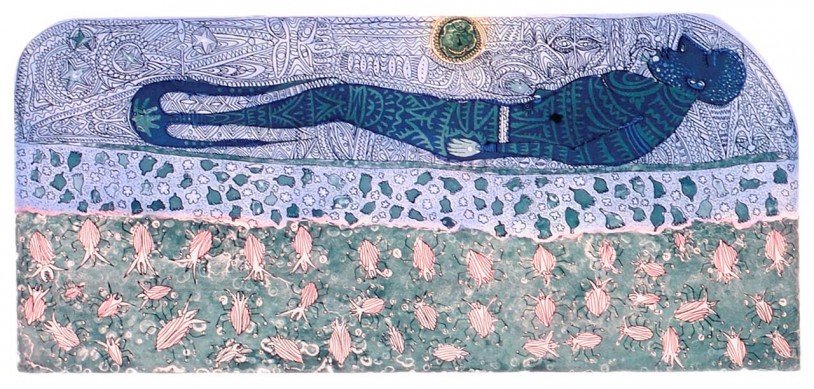

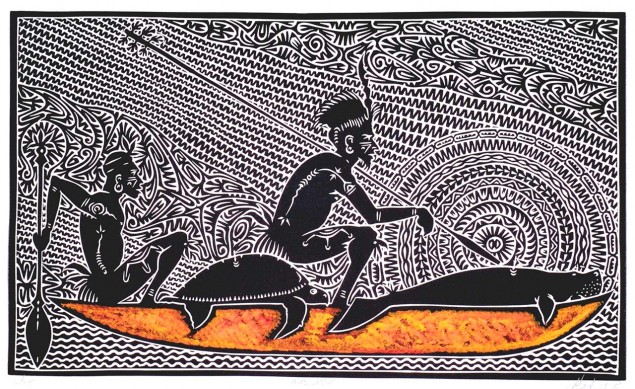

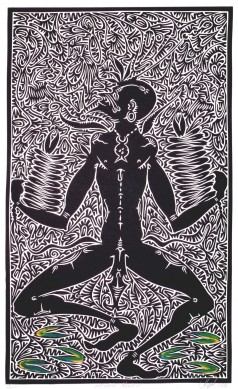

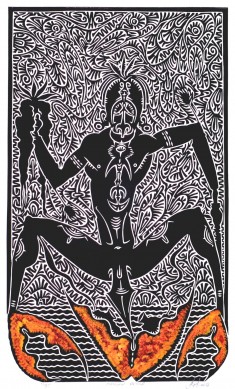

“ Dennis Nona and Alick Tipoti are from the tiny community of Badu Island in the Torres Strait, situated between the very tip of Australia and Papua New Guinea. In collaboration with the resources of The Australian Art Print Network, and access to the invaluable expertise of master printers they are riding a wave of unprecedented success.

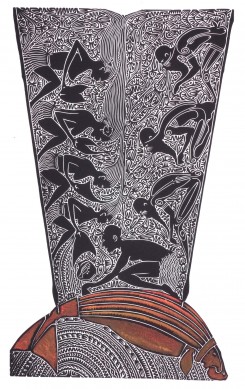

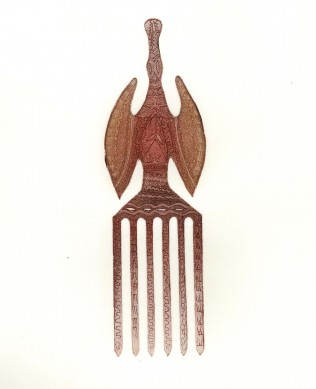

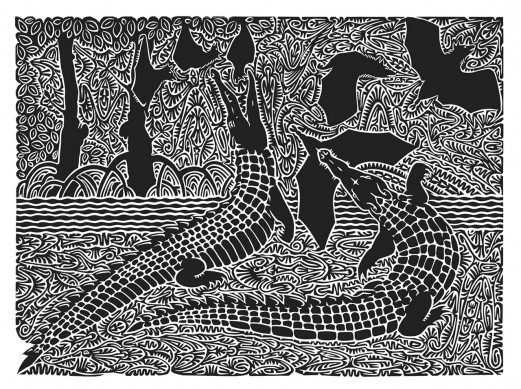

At home, in the Torres Strait, and elsewhere in Australia, Nona and Tipoti have become role models as cultural ambassadors through their art. In contrast with many young artists, both are keen to communicate whatever they can about their skills, technique and ‘trade secrets’. Nona’s ability to innovate and hone his practice within and across mediums in two and three dimensions is a hallmark.

Nona’s growing international reputation began with touring shows in the UK and Canada in 2001. In 2004 he was the recipient of the Angel Orensanz International Art Award, New York, and his work has now been seen in over seventeen countries with a string of solo exhibitions in London and Paris in the past 18 months. One of his first forays into sculpture, from a series of three substantive bronzes, entered the permanent collection of Musee d’Histoire Naturelle de Lyon in France in 2006, while major works were acquired for the collections of the British Museum and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

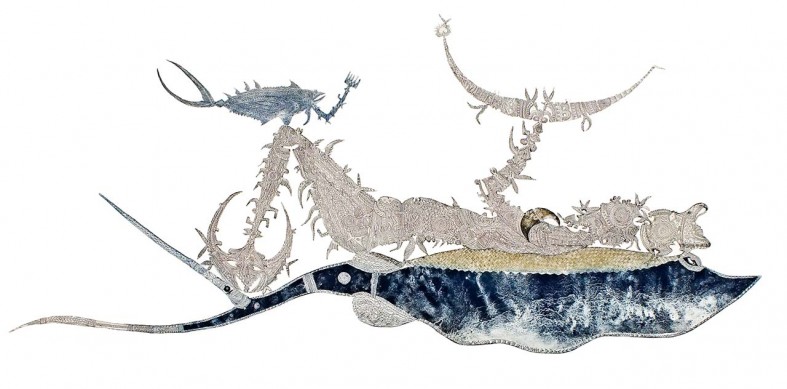

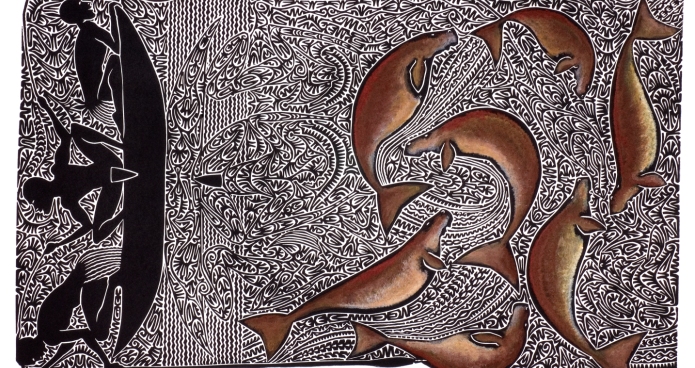

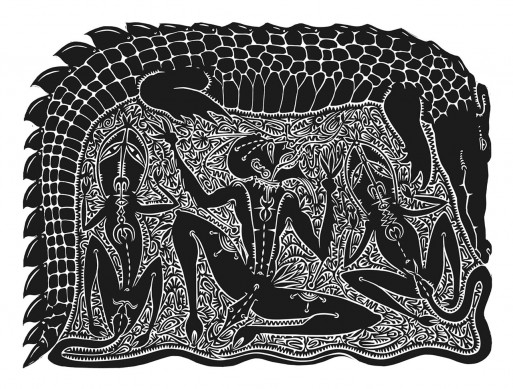

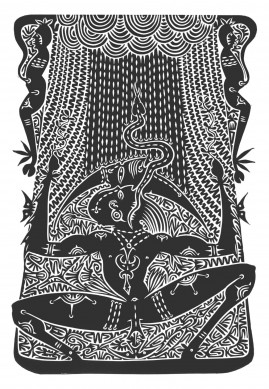

The National Gallery of Australia, Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney and Queensland Art Gallery also acquired his work in depth. Nona’s profile gained further momentum in 2006 with his inclusion in the ‘The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’, an event which launched Australia’s newest museum devoted to contemporary practice, GOMA, the Gallery of Modern Art. Deceptively lively, abstract works, Ara and Baidam (both 2006), proved the graphic power of his black-and-white editions, and were also acquired by major collections.

Working consistently since the early 1990s and now with well over 5000 editioned works in circulation, and almost 4000 of them sold, Nona can lay claim to being one of Australia’s most collected artists, with works in significant permanent collections around the world. His work is informed by the two worlds he moves between, fuelled on the one hand by an imagination and intellectual property only he can access, and from the other hand elucidated with unique technical mastery.

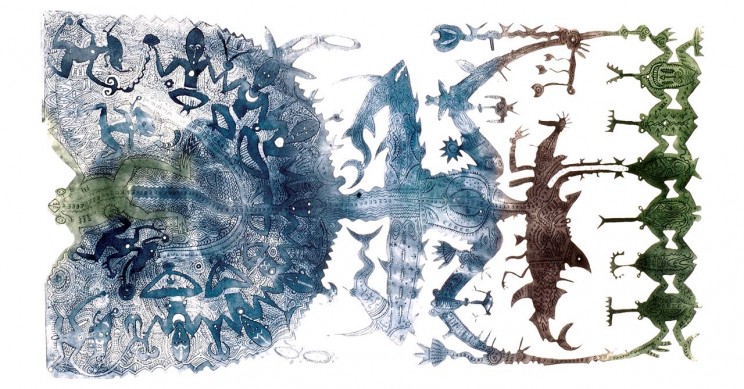

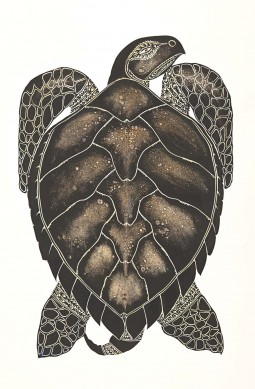

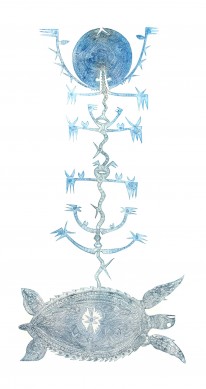

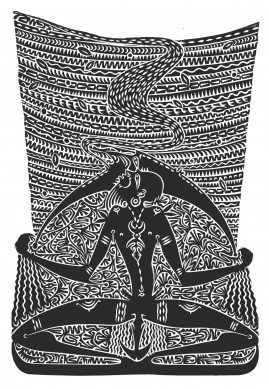

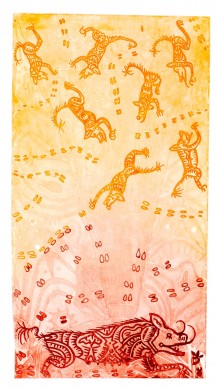

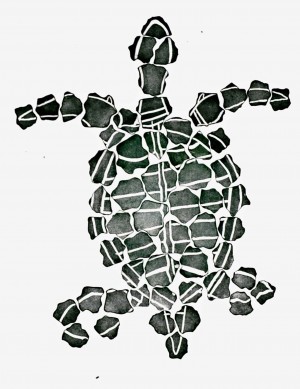

Central to Nona and Tipoti’s working methodologies is a desire to create art in association with protocols observed from guidance provided by appropriate island elders. In so far as their work relates to ancestral narratives, it is regarded as a kind of cultural document with historical and contemporary facets, and such a process seeks to ensure accuracy, acknowledgement and shared responsibility.

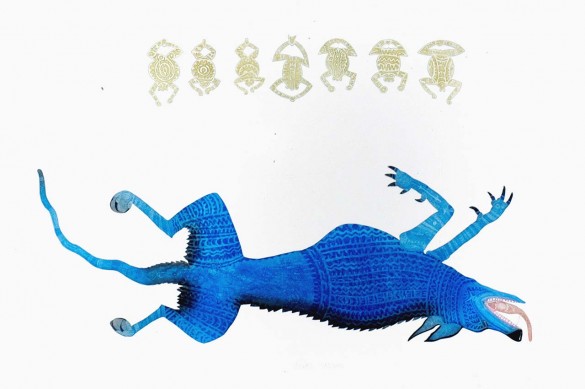

Tipoti is a young artist, born in 1975, and his authority to take part in these proceedings has a lot to do with the ways in which various communities value the conceptual significance and accuracy of his artwork. This extends a rare facility to the work, in so far as it can move from the gallery wall to be tendered as a legal document in Australian courts, as evidence to support sea claims, outlining fishing and traditional hunting grounds, and ancestral connectivity to place.

“I have always listened to the ancient stories told to me by my Baba (father), Awadhel (uncles), Apual (aunties) and other respected Kuyku Mabaigal (elders). As you can see when it comes to interpreting, translating or creating anything to do with my culture, my language plays a very important role. Language is the core of our culture.

Without your language you become a foreigner, lost in another person’s culture. One of my favourite English words is ‘analyse’. In my language we call it Ses Tham or Thapul. Singing and dancing are forms of art that branch out from the centrepiece called language. Everything you do, traditionally or culturally, evolves from a language. When you know the language, you know your culture.”

Cambridge University Museum, Kluge Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at University of Virginia, GOMA Queensland Art Gallery, National Gallery of Australia each have a number of major works by Tipoti, and his recent work Zugubal was recently acquired by The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Sydney, National Gallery of Victoria and Australian Museum, their first acquisition of a contemporary artwork for several decades.

Despite their individual pursuits and methodologies, Nona and Tipoti share great mutual respect and similar goals, and are increasingly being recognised for their efforts in communicating ideas in striking multi- dimensional forms. As children they went to school together on Badu Island, later they studied at the same college of advanced education in Cairns, and then at Canberra School of Art. As artists, they can be identified as the catalysts responsible for what we now recognise as a ‘school of contemporary Torres Strait art’

Simon Wright is Director, DELL Gallery at Queensland College of Art and Griffith Artworks, Griffith University, Australia.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In the rush to embrace our Indigenous arts, is the unique culture of the Torres Strait being overlooked?

Richard Watts | editor@artshub.com.au

Richard Watts is a Melbourne-based arts writer and broadcaster, founder of the Emerging Writers’ Festival

Creative Australia, the recently launched National Cultural Policy, has as its first goal a long-overdue recognition of the ‘centrality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures to the uniqueness of Australian identity’. This move to celebrate the primacy of Indigenous arts has been widely welcomed, but it also highlights an unfortunate truth about current attitudes towards Indigenous art in Australia.

Aboriginal art is increasingly recognised by mainstream Australia, but our other Indigenous culture – that of the Torres Strait Islands – is often overlooked when Indigenous art is discussed. The trailblazing touring exhibition Ilan Pasin, curated by Tom Mosby with the help of artist/curator Brian Robinson for Cairns Regional Gallery, which in 1998 was Australia’s first retrospective exhibition of Torres Strait art, and showed art works not seen in this country for more than a century.

On the screen the Blackfella Films/ABC telemovie Mabo (starring Deborah Mailman in a Logie Award-winning performance) brought the story of Murray Islander Eddie Mabo and his battle for land rights to a wide and appreciative audience. The ABC drama series The Straits, painted a less flattering picture of the Islands in the story of a drug-running, gun-smuggling family but it also gave the ABC an opportunity to disseminate information about the Real Straits.

The increasing recognition of Torres Strait culture is welcome but Torres Strait Islander artists have a long way to go before their unique culture is recognised.

‘Torres Strait arts – and culture in general – is generally sort of subsumed under the larger umbrella of Indigenous Australia,’ says curator turned fulltime artist Brian Robinson, whose recent work is featured in the Performative Prints from the Torres Strait exhibition.

‘The main reason we did exhibitions such as Ilan Pasin was to show the uniqueness of Torres Strait culture and to show that there was another Indigenous Australian race out there that could, you know, stand on its own two feet and was separate and had very distinct traditions that were separate from mainland Aboriginal cultures.’

Program Director of Queensland Music Festival Erica Hart, though not herself Indigenous, has worked closely with many musicians from the Torres Strait Islands – ‘People are mildly astonished, quite often, that it’s not just a part of Australia but that it’s a shire of Queensland, or two shires of Queensland, and that the islands are part of the Queensland government; that it’s part of our responsibilities, government-wise. And I think the Torres Strait Islanders do feel that it’s sort of like a semi-oblivion, that people don’t feel they exist,’ she said.

‘You could actually quite easily get those general assumptions of the Torres Straits being closer to, or more connected with Papua New Guinea and the rest of Melanesia,’ he says. ‘Maybe it’s the issue of people actually not knowing where the Australian boundaries are, how far they stretch from the Australian coastline?’

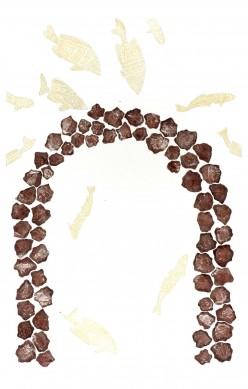

Like their visual art, the music of the Torres Strait is also distinctive, Hart says, with the rhythm set by the deep beat of the warup drum.

‘Their harmonies – their harmonies are quite unusual. A lot of the harmonics seem to reflect the movement of the sea – the sea is reflected in their painting and their dancing and their singing, and a lot of the traditional stories are about travelling around the islands and across and to the islands. There’s an ebb and flow to the music all the time.’

Born on Mer (Murray Island) and now based in Melbourne, musician and visual artist Ricardo Idagi says that for Torres Strait Islanders, music and art are a part of life. ‘If they’re gardening, they’re singing. If they’re cooking, they’re singing. And dance is also powerful – they’re always creating new dances; every year there’s new dances coming,’ Idagi explains.

‘It’s not deemed as art. It just happens, every day. You’re always telling stories, drawing patterns in the sand, always imparting – people are always doing that, but you don’t see it as art. Art is what you see in museums.’ Consequently, Idagi says, there are fewer Islanders who have chosen the arts as a dedicated career.

Though we have some way to go before Torres Strait Islander artists are as well known as such prominent Aboriginal artists as Emily Kngwarreye and Lin Onus, Warwick Thornton and Deborah Cheetham, projects like Ailan Kores and exhibitions such asPerformative Prints from the Torres Strait are slowly teaching the wider Australian populace about the unique qualities of Torres Strait Islander art and culture.

As Brian Robinson says, ‘The visual arts, performance, theatre – these are powerful tools, and it’s hopefully that through those creative mediums some of these barriers can be broken down, and more about Torres Strait culture can be understood by the wider population of Australia.’

Further information is available on exhibiting artists on the following links