Bush Dyed Textiles From Anindilyakwa Art and Culture on Groote Island

Japingka Gallery is exhibiting some very popular bush dyed textiles from Anindilyakwa Art and Culture on Groote Island. In this interview we talk with Lucy Bond, who is the Centre’s Arts Coordinator, about how the women’s textile project came about and its value to the community.

Where is Groote Eylandt?

Groote Eylandt is the largest island in the Gulf of Carpentaria and the fourth largest island in Australia. It’s off the coast of Arnhem Land. If you’re facing Indonesia, it is as far east as you can get before you hit Queensland.

It’s right off the coast of Gove and Yirrkala. We’re in the Gulf of Carpentaria but we are a remote tropical island made up of three small islands and a multitude of uninhabited islands. The two main islands are Groote Eylandt, which gets its name from Dutch explorers. The word itself translates as great island, so Groote Eylandt. Bickerton Island is a smaller neighbour.

There are three main communities as part of Groote – Umbakumba which is a smaller community, Angurugu, which is the main community, then there is Milyakburra community on Bickerton Island. There are groups of small outstations, but they are the three main communities on the Groote Island region.

How many people live in those three places?

It’s under 2,000 people. There is also the mining town of Alyangula, which is there due to the very large and very old manganese mine that’s been here on Groote for sixty years.

How would you describe the place to someone who hasn’t been there?

It’s a lot like Bora Bora. It has huge crystal clear reefs, and huge sandstone formations that drop straight into the sea. It’s got amazing turquoise ocean as well as a huge turtle and dugong population. It’s like you took a big chunk of Kakadu and dropped it into the Great Barrier reef.

How did this textile project come into being?

Lorna Martin is a very experienced art consultant. She originally employed Darwin artist Aly de Groot, who is well known for her textiles, fabric and woven artworks. She is also a specialist in developing new techniques for Aboriginal arts.

Aly was engaged to run a series of workshops through Lorna Martin, and began to develop the bush dyed textiles as part of those workshops. The workshops have become ever more popular and Aly has been coming to Groote regularly for three years now. Those skills have just continued to expand and grow, so that’s really how it has all come about.

What are the special problems relating to art making at the community?

Freight is always a major issue for us. It’s a challenge making sure that we actually have access to resources. If we forget to order paint brushes, or something happens to our paint brush order, it’s four weeks until we can get more. People really underestimate what isolation means. If you’re isolated on an island, as beautiful and as wonderful and as captivating as living on a remote tropical island is, there are logistical nightmares that go with that. Things take longer than you would expect them to. When somebody says, “Oh can you do something overnight.” You kind of have to go – no I’m sorry, that just isn’t possible.

You just have to be prepared for all sorts of delays. You have to have Plan B and contingencies for everything. You have to expect that things won’t arrive. What will you do if they don’t arrive? Can your workshop facilitators bring all their materials with them? If their excess baggage doesn’t get on a little flight how do you deal with that? Where do you get your backups from? How do you continue to do a workshop if none of your materials arrive on time? Ensuring that the isolation doesn’t affect the practice is really a big part of the manager’s job.

Why is a women’s textile project special to this community?

Women in Groote Island actually don’t own any arts painting or practice. Men own that practice on Groote Island. In lots of other communities the women have taken over parts of art practice. Sometimes they make certain traditional artwork practice their own. On Groote that really isn’t the case. The men orally own the two dimensional paintings and sculpture in Groote.

As there are very strict cultural protocols for men’s and women’s artistic practice on Groote Eylandt, the art centre had to find away to allow Aboriginal women to still be inspired by their cultural heritage though out their art practice, while not upsetting traditional protocols.

We found the best way to encourage this was through programs that have a natural connection to country such as the Bush Dying. The women use plant dyes for all of the silks and the plants are collected each day from around the Eylandt. The silks are then processed using a combination of techniques that the Anindilyakwa women have used to use to dye traditional cultural artifacts for millennia. These artifacts are items such as pandanus baskets, string bags and other ceremonial regalia. Now this is being extended to include silks and the new practice taught by Aly de Groot during her workshops.

They are still tapping into this ancient craft of womanhood while implementing it in a new and modern way, which traverses that world of male ownership. You can still have this modern platform with very traditional techniques being produced by women so that you’re not stepping on any toes.

Where do you beautiful dyes come from?

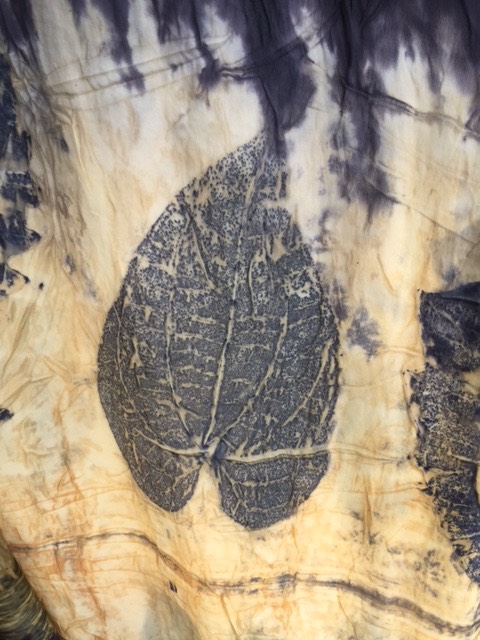

Dyes are all from plants that are native to Groote. That repertoire has been built up over the amalgamation of the women’s technology that they have been doing for generations and millennia, and Aly de Groot’s knowledge of plant based dyes. There’s an amalgamation of both those techniques, but the majority of colours come from things that the women have used to dye products in the past. They’re tapping into that local knowledge, and black is the really iconic colour for Groote, because Groote has such a high concentration of manganese, and manganese is jet black.

The ground at Groote Eylandt is jet black the way that Kakadu is red. I think that a lot of the women naturally gravitate towards the black dye. It is made from the leaf of a tree. It does hold an identity to Groote Eylandt, and how Groote looks from the air and the ground. That beautiful manganese black, which permeates all of the landscape there.

How are the individual artists developing their ideas and styles?

That’s been a fascinating part of the creative development. Deserall Lalara, and her sister-in-law Litoria Yulijirri both have a somewhat loose creative style, where leaves and other materials are placed in a random way throughout the silks. You see a result of a beautiful mesh design coming out in a very botanical, quite natural way. Then you’ve got other artists like Candida who’s an Umbakumba artist and others who prefer more precise positioning. Candida absolutely likes every leaf to be symmetrical. She will cut the ends off leaves that aren’t perfect shapes.

The artists collect leaves for the day before we do workshops to make sure that they’re all the perfect shape, the same size, and that they’re going to be arranged in a specific way. I think the people’s personalities tend to come out in their particularness or lack thereof. It’s really interesting that over months of women being engaged in this programme, you can start to actually pick which artist did what work. The same way that you can with a painting, just based on their plant and dye selection, and how they choose to actually orientate their leaves, and what plants they choose to use in their printing process. After a while people do really start to develop their own identity about the manufacturing process.

What are the ages of the artists?

Artists range in age from 18 to 70.

How many do you have in your textile group?

At this stage I would say women that have worked with us probably over the last four months would be in excess of 50.

Can you describe the process of making something like a silk scarf?

The first step in that process is to go and collect the leaves that you want to actually create an imprint onto the silk. The women will go out and there are certain leaves that make better imprints than others. They will go out and select which leaves or what botanical themes they actually want to have imprinted into their silk. Then they will go and collect all of their dyes that they want those silks to be covered with, as well as rusty objects from the dump. These might be beautiful cogs, and wheels and pieces of wire. That kind of very recycled, earthy, rusty element too, which is at least part of their identity.

From there we take all that back to the Art Centre and we boil up old flour drums full of colour. The women will wrap up the silk with the plant matter that they have selected, and the rusty items from community that they have collected. Then we will boil those silks in that dye for about an hour, and then we will take them out, rinse them all in the sink, and hang them in the sun to dry.

What story do you think these hand made designs tell about the community?

When I worked in Maningrida and in other traditionalist painting communities I came to understand the value of the art. People underestimate the fact that when you buy a large bark painting you are literally buying a tree. You know you’re literally buying something that grew out of the land in that place. There is something really underestimated about how important that is. People always think about buying a painting, but they don’t actually think about the fact that thing had to grow from a seed in that place.

I think that’s true of the silk designs. Every single silk is coloured by a plant that grew on Groote and was put in rusty pots that were found in the dump. They’re a complete representation of daily elements of community life. It’s that uniqueness to explore and want to help Groote, not to mention helping the women themselves, by an amalgamation of botanical knowledge that grew up in that place. It all makes the silks so special and unique.

How would you like to see this project develop?

I’d like to quote the words of Bernadette Watt, who’s our Senior Project Officer at the Art Centre. She was asked recently who she would like to see her silks worn by, and she said, “She’d like to see them on the runway with Magnolia Maymuru.” She is a Yolngu woman who become the first Northern Territory woman to make the finals of the Miss World Australia pageant.

What excites you most about the results so far?

For me, it’s about self determination and engagement. When I took over at the Art Centre there were very few artists regularly practising and recently we hit over a hundred people being represented by Anindilyakwa Art and Culture.

I think that’s a real testament to the success of the programme and a testament to the women who have continued to teach their knowledge to younger people and more interested artists. We pay artists by the piece, so every single piece of work that these women make and have dedicated their time to, they are paid for.

That has also given rise to a cottage industry that’s allowed people to make more financial decisions. Eventually we hope to bring people to a much more self sufficient place. This will happen if we can continue to expand the audience that we’ve got.

I think that’s what’s really special about it. The women have been talking about their identity. They talk about how they want their logos to be, how they want their roots to be represented. They decide what the tags should say when we send them to different galleries. They sometimes decide how they want them hung.

I think that this new knowledge base about representation and their identity is becoming much more important for each of the individual communities. They want to be known as Groote Island artists. They also really want to be known for the community and the place that they come from, their Country and the reason why their work is different.

I think that’s a real strength. It gives us a huge amount of diversity. It also means that this programme and others give people an opportunity to be proud and to have a commercially, saleable, beautiful, organic handmade product that is unique to them.

View More: