The Pintupi Artists of the Western Desert

In this article David Wroth takes you on a walkthrough of the Pintupi Artists exhibition.

In Gallery 2 we have the exhibition Pintupi Artists of the Western Desert. It’s said that the human brain is built for recognising patterns. These Pintupi artists have an extraordinary talent for creating structured patterns and designs that represent different aspects of their culture. The works are representing the desert country, representing Tingari or Dreaming sites, representing ceremonial sites and places of significance.

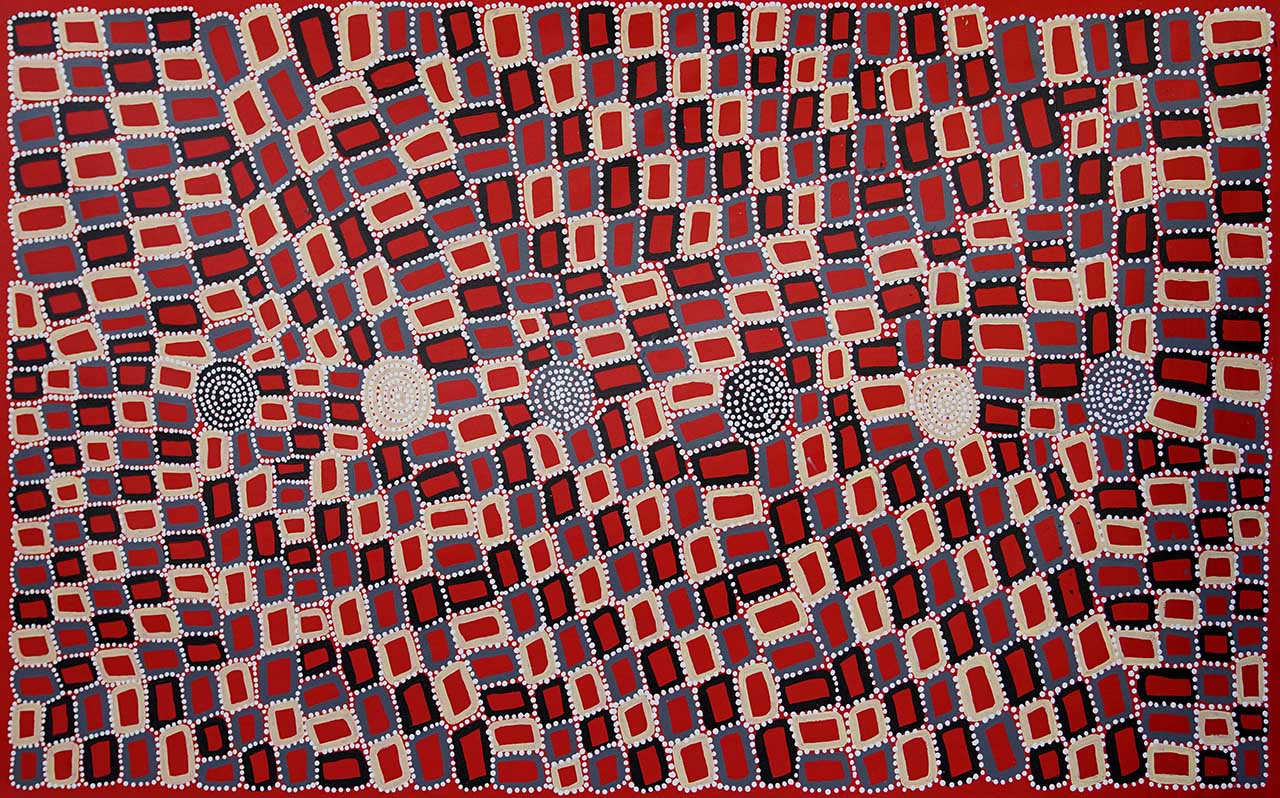

We’re standing in front of a painting by Walala Tjapaltjarri… all his works are titled Tingari, referring to the men’s ceremonial and Creation narrative that forms the basis of Law for Pintupi people. The whole painting is composed of small rectangles broken up with rows of dots and central concentric forms representing waterholes. The painting is typical for Pintupi style in its use of pattern and repetition to build up structures that become recognisable as features of Pintupi art. The patterns are highly significant, coming out of the symbolic language used to transfer knowledge about Pintupi culture and Law. Each artist tends to enhance and develop their own signature use of designs that represent their country and therefore these compositions of designs become associated with the style of that particular artist.

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa has created this striking and linear painting representing Water Dreaming. There are repetitive lines of colour where he has dipped the brushes in a range of colours that merge from deep blue through aqua green to pale blues and whites. The whole structure blends from one colour to the next making a maze of the lines that seem continuous. The effect of this repetitive series of maze-like forms painted in blue tones indicates the power and strength of the Water Dreaming story for desert people. Ronnie’s designs are highly refined, very minimal, reduced down to rows of lines that are highly irregular and asymmetrical, perhaps following in the landscape of his country. This artwork is painted on a silver grey background so it hums with the flow and feeling of a Water Dreaming story.

The other aspect of Ronnie Tjampitjinpa’s structures is the Fire Dreaming story. Again we see parallel lines blending through the colour range of reds, oranges, golds and yellows. There is break-line through the middle. Perhaps that is representing the control of the fire on country. There’s always this break when no lines can get through and there’s just the black of the background colour of the canvas.

This is a different kind of design-making or pattern representation from Walangakura Napanangka (1946-2014) who is one of the great women artists of Pintupi culture. Her designs are focused on women’s ceremonial sites found in rocky country, so the locations are highly significant in women’s Tingari Dreaming mythology. To emphasise that the locations are in very rocky country we get these large concentric circles dominating the canvas, and we get lots of small circular rocks and rocky outcrops completely filling the spaces in between. So the painting becomes highly active, very irregular in its rhythm. But the whole composition being based on these circular motifs, the whole thing pulls together as an image of ceremonial country amongst rocky outcrops, and it is once again a signature style that identifies an artist from Pintupi culture.

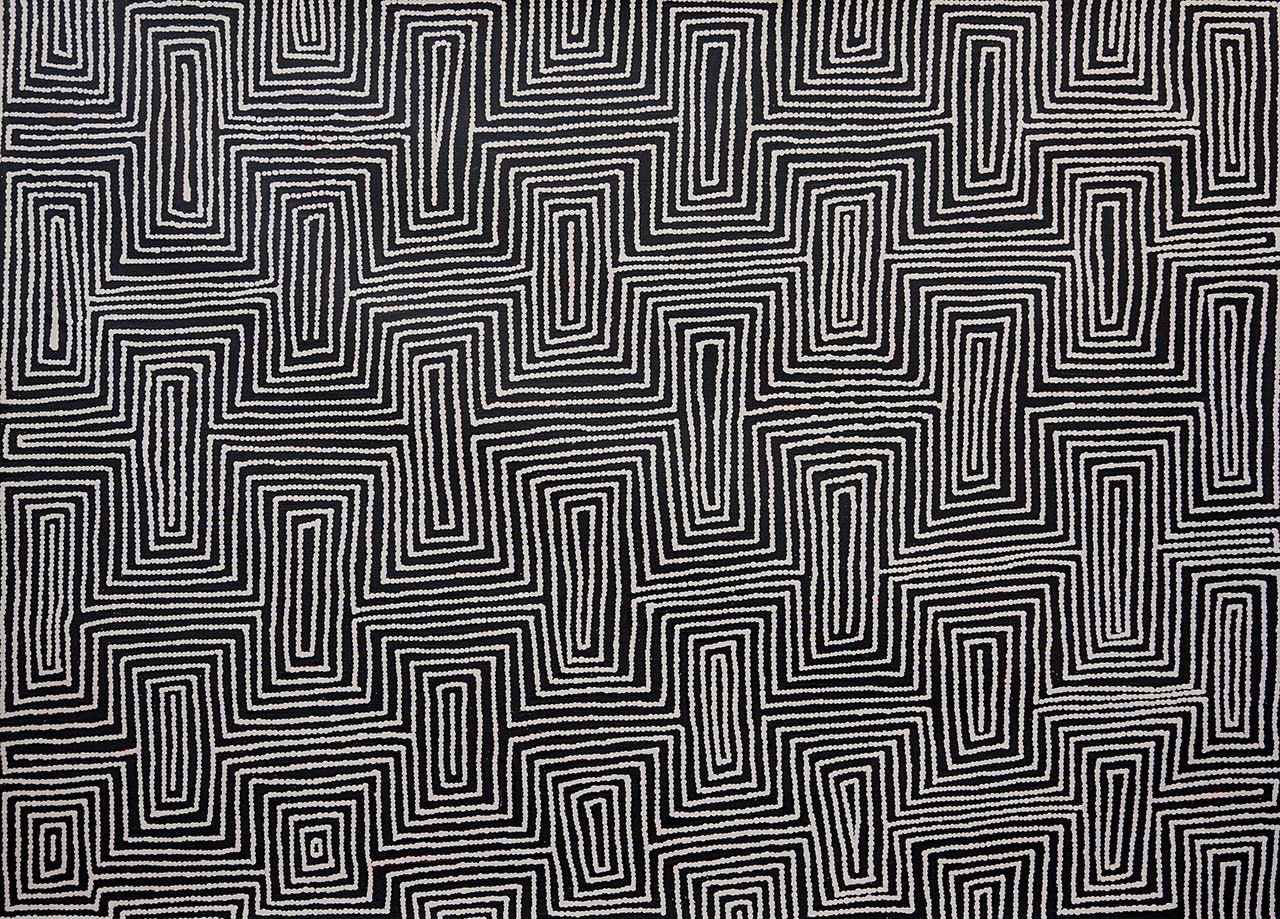

George Hairbrush Tjungurrayi paints Tingari designs that are very optical, which is another aspect of Pintupi art. The lines meander and fold and break across the canvas. They’re painted in contrasting colours, in this case it’s red and white alternating colour. The designs are hypnotic. They are very optically challenging. They pulse and move in front of your eyes if you stand and look at it for some time. This is another aspect of Pintupi pattern making where the artists use the repeat pattern structures right across the canvas. I think it expresses the enormity of the country of that vast desert terrain, and maybe also the hypnotic quality of the landscape.

Jake Tjapaltjarri is the son of George Hairbrush. His painting called Father’s Country uses a form of keyhole imagery, these interlocking shapes almost like vertebrae, parallel rows of designs that mesh together across the canvas. This creates a very optical effect so you can’t really stand and look at it continuously for any length of time. There’s a repeated pattern made up of rows of dots that form the interlocking shapes. The patterns pulse with movement and energy, just as the landscape does if you were flying over it. It is an expression of the expansive and important aspect of life and the land in one design. The human brain recognises that it is a design about the Creation process and the structure of the land more than specifically about any terrain or landscape you might see on a map.

It was expressed to me a long time ago by an elder who was a stockman, he spoke of the patterns as a brand. He was using brand in the sense you would brand cattle to show what station they belong to. In that sense he was saying these patterns are brands belonging to the owners. So these traditional owners could be recognised for their home country simply by the types of patterns on the ornaments and artefacts that they carried with them. This is almost like our modern sense of the brand, which travels across time and territory. And in this case people recognise these paintings and the imagery as an expression of Pintupi culture. This is a small and quite isolated culture, but the strength of the branding that they create and have expressed in their painting is truly significant.