Omie Artists Barkcloth From Papua New Guinea

Gallery 2 features fibre art from two very different locations. On the walls we have barkcloth or nioge which are made in different villages of Oro Province in Papua New Guinea.

The women artists from fourteen villages have formed a cooperative to show their art around the world. The cloth-making is a fascinating process. The materials all come from the natural environment. The fabric that is like felt to look at and touch. It is made from the fibre of palm trees from the tropical forests. The women have pounded the wood pulp into flat sheets and after drying have painted on them with designs of tribal, family and cultural inheritance. They’re very organic in their feeling. They combine layers of natural materials from the jungle, tree pulp with organic dyes extracted from plants. Sometimes some volcanic mud is used to give some deeper grey-black tones.

The women from this group, the Omie Artists, have relied on designs that are either of the environment or a part of ceremonial and cultural designs that belong to their people. There was a time when the indigenous people of this region had the custom of tattooing ceremonial designs on their bodies. After the arrival of missionaries in the area this tattooing practice was discouraged. The artists then began to transfer the designs onto barkcloths or nioges.

Photos from the area show people wearing the barkcloth with these designs as garments, they look a bit like a sarong. People wear them as clothing for ceremonial events and they use them in everyday life in the village.

This barkcloth is 113 cm long and 57 cm tall. These works have a very tactile quality. They come with a certain feeling of age and a feeling of the environment because they’re not using any modern dyes or synthetic colours. The colours available to the artists are straight from the earth and they reflect that strong sense of local environment.

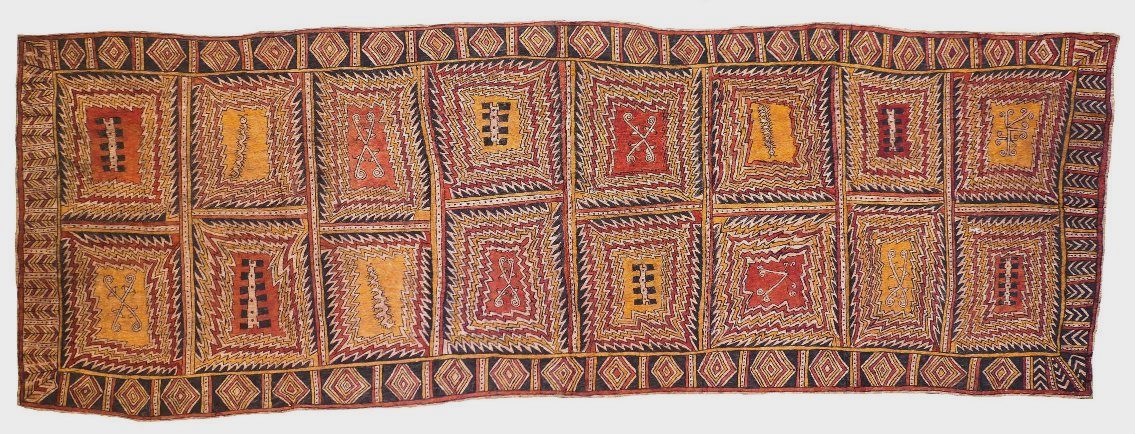

In the main archway of Gallery Two there are two longer examples of barkcloth, each around one and a half meters long. The first one features designs of the Omie mountain and patterns of the beaks of the Papuan hornbill bird. It’s a fascinating design. It feels more like a village rug design that we might be familiar with out of the Middle East. Around the edges there are diamond patterns relating to the volcano shapes. The area where these works come from has very steep valleys in the shadow of a volcano. It’s an extraordinary landscape.

This particular work by Diona Jonevari uses very deep colours. The tones remind me of tobacco red and deep Indian yellow colours. The dyes have soaked into the barkcloth and that gives it a very soft mottled colour. They form intricate designs picked out with black lines and patches of the off-white barkcloth coming through.

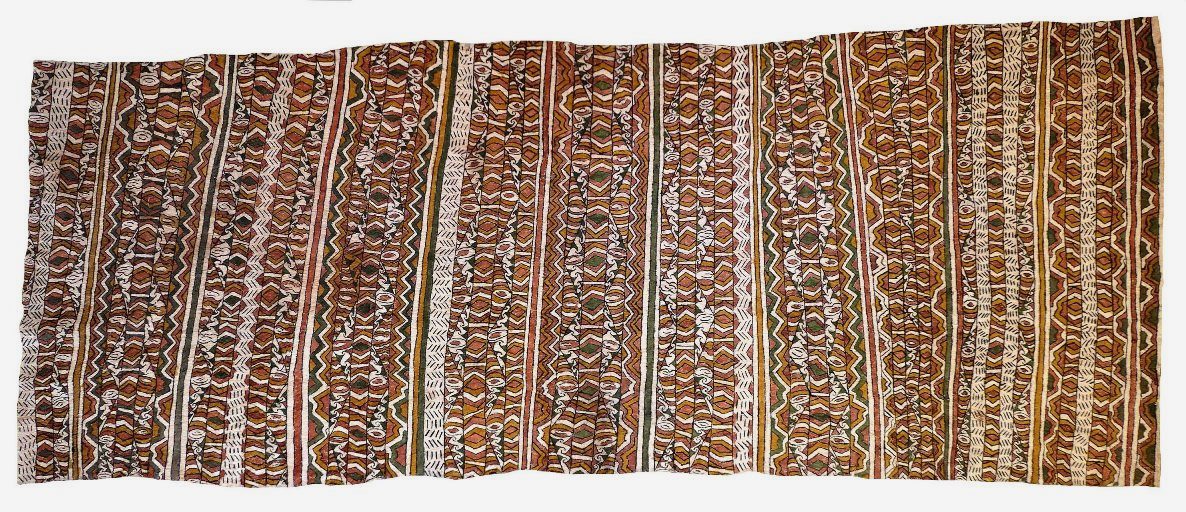

The next work by Lillias Bujava is another complex design. It also connects with the image of the Papuan hornbill. This is an intricate geometric set of designs which are repeated down the cloth. There is a geometric effect running down the one and a half metre length of this artwork. The pattern is constantly changing, all held within a fairly close group of earth-based colours. This design uses an olive green which is more unusual. It combines with the warm earth colours tied together with very fine line work.

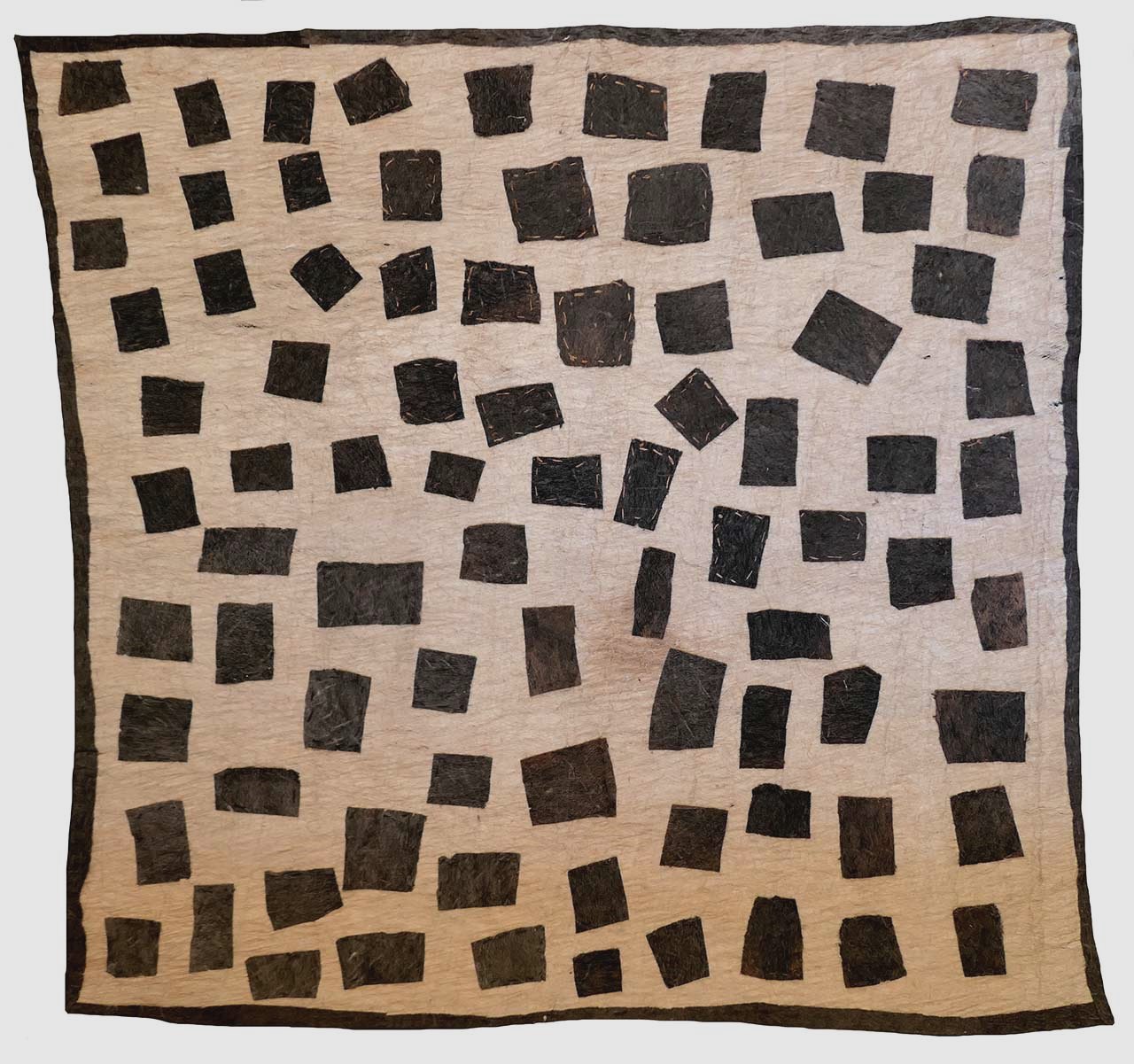

This work by Ilma Savari is in contrast to the finer detailed designs in rest of the exhibition. The artist has sewn strips into a geometric design. They are very simple. The first one, tail feathers of a swift, is again the design based on birds from the area. It has a geometric and structured modern look to it.

The other very unusual barkcloth next to it is a large square which is marked as an ancestral design. The artist has simply sewn sections of the dark grey mud-stained barkcloth onto the base cloth. There are many markings randomly moved across the background colour. It suggests a modernist design where the connection to any object in the landscape has been removed. It’s a wonderful piece, a contrast between dark and light. There are the heavy grey squares laid out on a pale background.

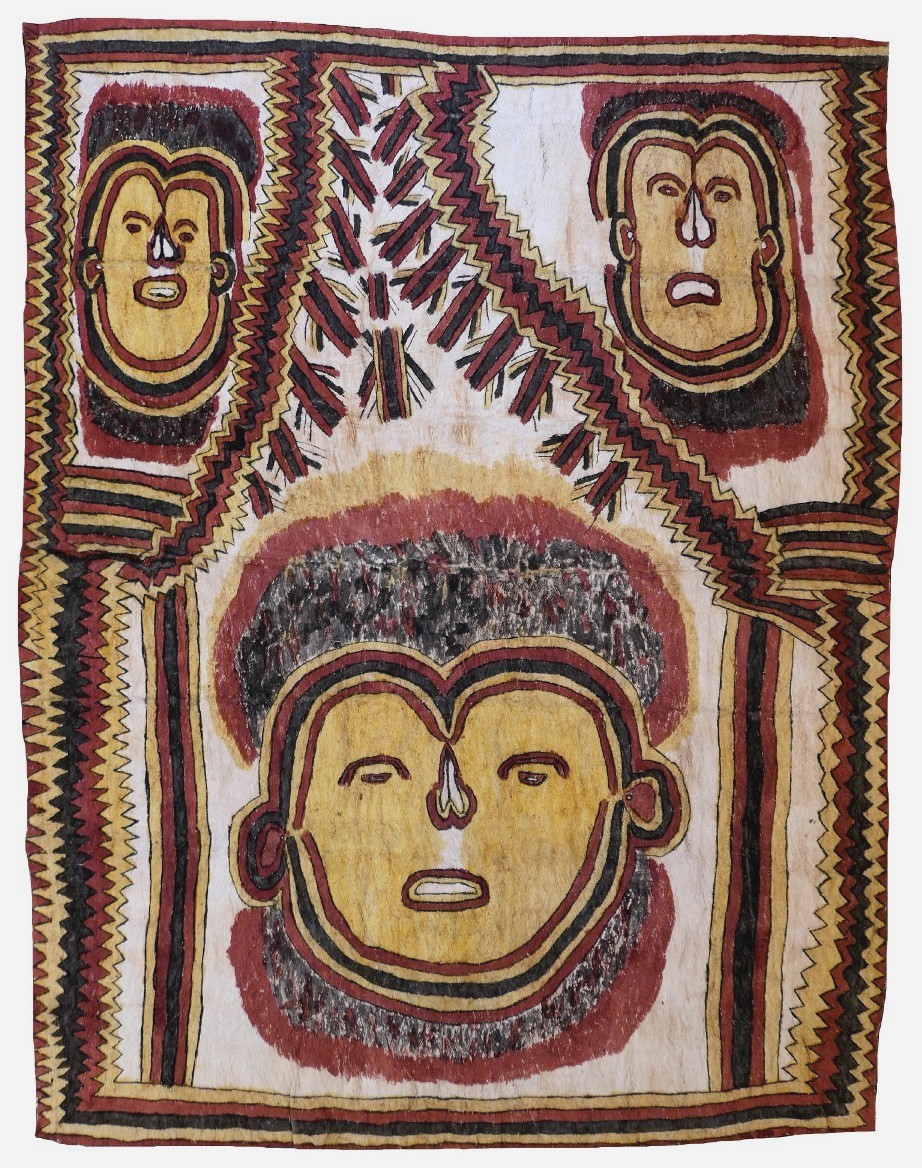

Another design by Ilma Savari is an image of a clan man. This is the only barkcloth in the exhibition from Omie Artists that has a figurative element to it. One of the aspects of all these designs is that they are connected to traditional designs that were used in ceremony as either body paint or tattoo art. This particular bark cloth has three faces on it. They’re quite large, marked out with ceremonial lines around the profile of the head. The whole design is broken up with zigzag shapes and bands of colour. They connect this type of art back into its ceremonial standing. It also links to the Ancestor stories, to the clan groups and tribal groups who own these designs.

One really interesting fact about the Omie artists is that they are among the only indigenous cultures in the world who are still using barkcloth and painting it in a way that connects to a very old heritage. Most of the tropical regions around the world have had traditions where they’ve created their own cloth from vegetable fibre, and subsequently decorated them as clothing and ceremonial items. These traditions existed across Asia, Africa, South America and across the Pacific Islands. Indigenous groups are ceasing to make these traditional cloths in an era when you can buy a ready-made cloth from a general store. Art forms like this become an endangered art; they’re no longer processed and made by people, and they’re no longer a very integral part of these indigenous communities. So Omie Artists from Papua New Guinea, when they show this art are sharing some of these very old traditions that have managed to continue on into the modern era. We’re seeing this artwork coming from a very remote Highlands area that is difficult to access. It is exciting to see these barkcloths exhibited at Japingka Gallery.

View: Omie Barkcloth Art – Papua New Guinea