Microscopes, Paint Brushes & the Bones of Life

Professor Nadia Rosenthal has a Ph.D. in biochemistry at Harvard Medical School. She is an award winning cell biologist and passionate Aboriginal art collector. Nadia is currently Scientific Director and Professor at The Jackson Laboratory for Mammalian Genetics. She is described as “a superb scientist, a keen intellect, an outstanding teacher, a visionary leader.”

Nadia talks here about her response to Kurun Warun’s exhibition at Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery and about moving her collection from Monash University to the location of her new laboratory on a remote island off the coast of Maine.

Could you tell me a bit about what you see when you walk around those walls and look at those paintings?

I first got to see them about a week ago in the exhibition brochure. I was immediately struck with this biological feeling in the paintings. It could be seen as a bit facile to relate something that you know very well, in my case biological image, and overlay that to insinuate a new meaning onto an art form. This is especially true as this goes back so long and that has so much of its own mythology and imagery associated with the figures and the shapes.

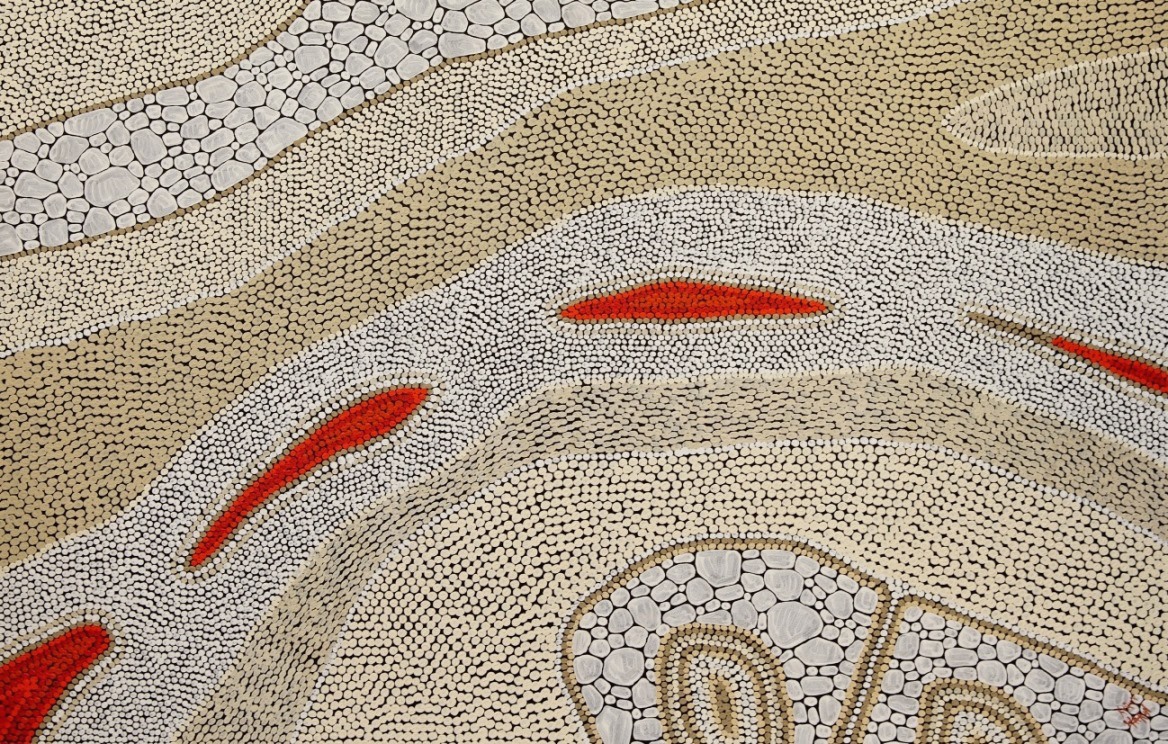

But it continues to strike me how much Aboriginal art looks like the biology that I spend my life looking at. It’s tempting to think that the reason that the indigenous eye has such an affinity to those shapes is because of some subconscious sense of biological form.

I once took a microscope into an art community in Australia and asked them to look down the microscope at some of the work that I do, so they could see why I am so drawn to Australian Indigenous art. It is because of the way it reminds me of the cellular structures that I see. Muscles, hearts, sinew – but at a microscopic level.

Kurun Warun has really taken this to a new level because of the precision with which he paints. His painting is extraordinarily exact, almost architectural.

It is very easy for me to make the association with an archetypal shape and form that you see in a biological specimen under the microscope.

For instance, when Kurun described camps to us, he was talking about the beautiful slits of red in his otherwise rather pale paintings. Camps, where life is. I had just told him that I thought it looked like the inside of a bone, the marrow of the bone where the blood is made. The bone itself is not living, but the marrow is. The environment of that bone is absolutely critical to protect the marrow, and to give it the right signals to make blood. We need blood everyday, that’s an ongoing process in your bones that happens for the rest of your life. It was poetic that he called these blood islands, “camps of life”, because that’s exactly what they are in the bone.

In any case, all the other ones were packed up in huge crates, and arrived in a remote island off the coast of Maine. I am now running the largest institute on mouse genetics in the world.

It has quite an impressive art collection already. It’s got endless corridors and labyrinth line connections between buildings, because it’s been growing for 80 years and it just adds stuff onto existing architecture. There’s ample opportunity to find a place to put art. I’ve been populating the halls with Japingka art slowly.

I’ll put up a couple, and then I’ll send around a notice to say, “Go to a particular hall and you’ll see two Elma Granites paintings, one next to the other. Two depictions of the Seven Sisters, Dreaming, that she paints all the time, and beautifully. They’re huge. I describe who she is, and I send around in the email, a picture of the artist. I take excerpts from the Japingka catalogue and put that in the email. I tell them a little bit about how Aboriginal painters derive their images from the dreaming and the mythology of their culture.

The first time I did this, the response was amazing. Within 15 minutes, I have 500 people to whom this email goes, within 15 minutes I had 10 different emails saying, “I’ve been down to see them.” I actually found people wandering the halls looking for them, because now they were very excited to go and find these paintings that they had just read all about. I then had an email from one of the senior faculty, saying, “Thank you so much for doing this. I’m going to lend you four of of my Aboriginal art books.” Another person wrote and said, “I love this. Can I find out more about Aboriginal art?” Of course I gave them the link to the Japingka website.

As I was saying to Ian, there’s something special about taking indigenous art out of Australia, because we’re saturated to some extent here. I mean, not as much as we should be saturated. You do see a lot more examples of really glorious indigenous art walking through the Australian public space. It’s rare to see it in America, and especially rare to see more than one painting by a particular artist.

For instance, I have a Jack Dale painting in my office. People walk in, and I placed it so that when people sit to talk with me, they’re staring straight at this huge Jack Dale painting. Of course, it’s white blood cells and red blood cells in it. The whole thing is, people look at it and go, “Oh! It’s white cells and red cells.” I say, “Yeah, I know, but that’s not what it really is. It’s actually has to do with waterholes. It doesn’t have anything to do with the blood.” It has, I think, it started to excite people about walking through the halls and being exposed to these paintings in a way that my previous Institute has gotten quite used to.

I feel it’s part of my duty to continue to collect.

Is there any work tonight that sort of captures your heart?

Yes. There are a couple. The problem is, that I have a wall that I have to look at all day long because the Jack Dale is for my friends who come into my office to see. I’m facing a wall that I would like to be able to enjoy something there. It’s very hard to put a painting in a room with a Jack Dale, especially one of that graphic nature that won’t just get eaten alive. The one I have in there now, I tried one of the Granites in there. I felt that it was unfair to Elma, because the subtly was lost because of the juxtaposition of this hugely graphic painting.

Do you think this work in here is strong enough to sit near a Jack Dale painting?

Yes, so I think it is. I think it’s the confidence with which he paints that I think will come through, and hang together with the mastery of the Dale. I’m unfortunately limited in the space that I have to hang this painting. As a result, I can’t get one of the big ones. I think I can probably fit one on others.

I’m not really actually going to buy it for the space, I’m going to buy it for the painting. If it doesn’t fit there, I’ll find another place.

Read more: