Kurun Warun On Country, Choices & Living Culture

Interview with Kurun Warun at the launch of his solo exhibition at Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery – February 2017. Kurun’s family ancestry includes Truganini and he comes from the same tribe as Lionel Rose. Given his first set of boxing gloves at the age of two, he grew up learning to fight, but his true calling turned out to be art.

How does it feel to be in this space with all your work around you?

It just feels great. I wouldn’t have imagined this as a child on the mission. It wasn’t trendy to be a black fellow back then. Not like it is now. (Laughs) I reckon you could write a book on that, call it “Trendy To Be A Black Fella.”

I just love it that people actually like the paintings. Some people really love them. You know, it’s nice. You hang a painting on your wall, and some people cry and hug you. You can’t get a better feeling than that. I love it. I pinch myself. It’s still unbelievable, I still can’t believe it. It’s been happening for a while now, but I never get sick of it.

How long have you been working on this particular body of work?

Just on and off, over a year. I bought a couple of pieces over with me yesterday so some of it is very fresh. When I paint, I just get focused.

Is there a painting in this exhibition that’s got a special significance?

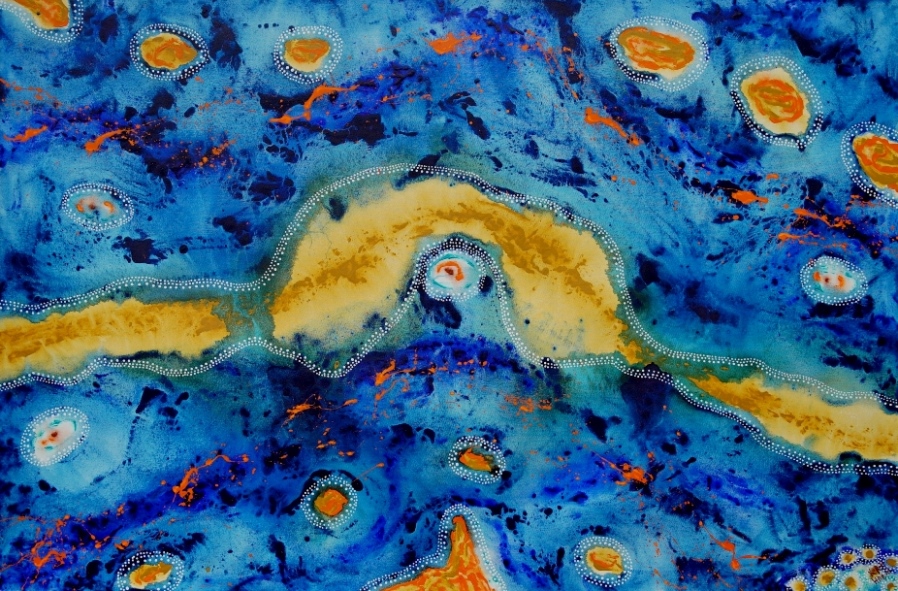

It’s called Pundin Pooreyt, the translation is Living with Water. There’s a sandbar in the bottom right-hand corner, the mud crabs, there’s fish traps and the island, like the land and rocks. The orange that comes through is the water life. This it’s about looking after it because if you look after it, it’ll look after you.

My children learnt to swim in this place. So all of the kids have always gone to this place. We’ve been going there for over 20 years now and love it. Every opportunity we get, we go to this place. It’s up near Noosa. That’s what it’s about. Like the rest of my art, it’s all living. It’s still happening.

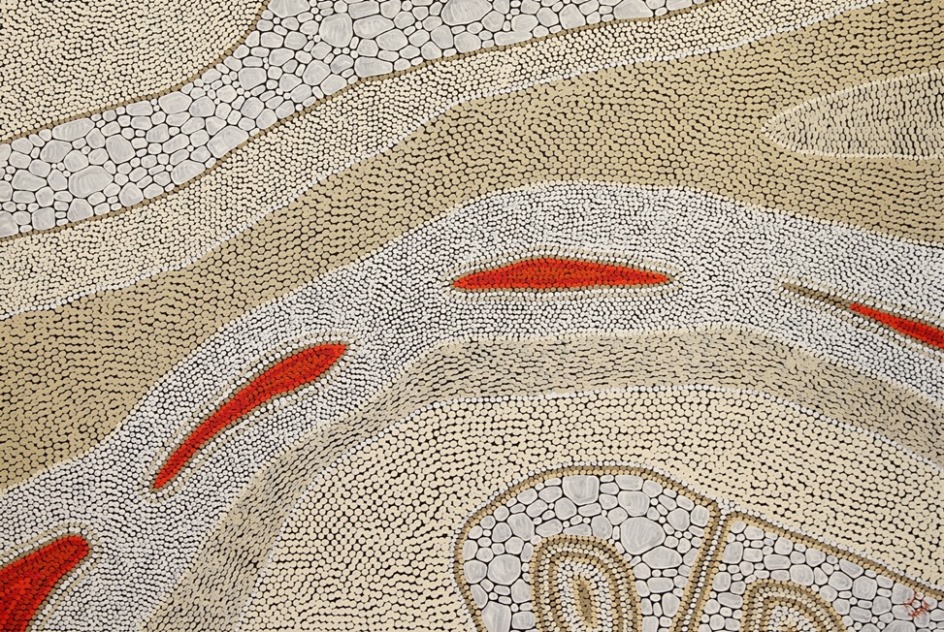

I also love the painting of Kangaroo Hunter because it’s a nice dance. That painting canvas is getting stretched today. I’m going to tell that story tonight on the didgeridoo. I’ll tell the story before I play it. People will see it as I play it. The didg, the painting, and the dance is all tied up with the painting.

What part of Australia did your ancestors on your mother’s side come from?

Our tribe’s Gunditjmara. That’s the Grampians, Great Ocean Road. My great-grandmother is the granddaughter of Truganini. She came across with Robinson in 1836 to Port Fairy. So that’s where they hooked up with my relatives. I’m fifth generation from Truganini, a direct descent from Truganini. That’s where we come from, the Grampians.

Can you describe what that sort of country is like?

It’s beautiful to look at. The mountains around the Grampians. Waterfalls. Great Ocean Road. The coast, it’s cold, windy. I don’t live there now because I live in Queensland.

What’s known about your ancestors?

The possum skin and cloak. Beautiful cloaks, I’ve seen them. Shelters were dug into the ground and the roof was raised a bit higher with the skins over the top. Then when it rained, it didn’t let the water in. They also had mittens. They used fish traps in the water.

When you go back to some of those areas and you go into the country, how does it make you feel?

Oh, I love going back, to visit. (Laughs) I have a lot of memories as a kid from out on the mission. That’s the same mission Archie Roach sings the song about, Took the Children Away. The stolen generation, part of those events took place there. Archie was one of the children taken. There is a line he sings that always gets to me.

“One dark day on Framlingham

Come and didn’t give a damn”

Mum used to mind Archie before he got taken. He was about two. Mum was 16 so she never got taken. It’s terrible. At the last concert of Archie’s that we attended he started singing the words “one dark day on Framlingham.” He calls out “Tio”, because that’s my nickname. I just broke down then.

How did you learn about your culture?

Since I was very little I would be with old Uncle Muscles, he’s Mums brother. He was always carving boomerangs. I’d have to climb up the tree to cut the branches for spears. We’d always be carving boomerangs and spears. I just grew up with that side of things. I would go hunting with old Uncle Banjo, Banjo Clarke. You ever heard of him? They got a book about him called Wisdom Man. So he raised Mum as his own daughter because grandfather got killed by the coppers.

So Uncle Banjo raised her. That’s a whole story of Uncle Banjo. It was a state funeral, and the Prime Minister was there for his funeral.

So Banjo used to take me out in the bush. And old Danny Roach would take me out in the bush, and we’d just learn so much from the old fellas. As a kid, I was always interested in it.

But there was so much drinking and fighting at the mission. I remember as a kid, they had glass flagons and I’d put them in the dam and I’m just smashing them with rocks. I was with my cousins, I remember saying, “This is not going to be my lot in life.” I kept smashing things. I was only in primary school, very young. I said “No way am I going to be out here drunk. This is not going to be my life.”

But I loved it as a kid. We loved it. That’s all we knew. We used to fight, fight, fight, fight. Grew up fighting. I got my first boxing gloves when I was two because as I was saying earlier, my Dad comes from Italy. Three fights, three knockouts. His dad was a wrestler. His uncle was the heavyweight champ of Italy who went on to become Al Capone’s bodyguard. Our tribe included the boxer, Lionel Rose. I was supposed to be a professional fighter. But by the time I was 12, I said: “this is not going to be my job.”

I had my first exhibition at eight, but then I stayed away from the art for 25 years. Little bits and pieces, like I was just a bit wild. Then when I got to Queensland, that’s when I started. Got back into the art. I’ve lived a couple of lifetimes.

In terms of culture, what is it that you find yourself explaining to people that is just not understood?

People think that the Aboriginal people have this Utopia. And they know how to look after the land and the animals. But it was no Utopia, with the human side. Beautiful. Beautiful people. But when things go pear-shaped, it goes pear-shaped. The Sorry thing (Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apology to the Stolen Generation) and all that. I said, “well great for people that want it.” Me? No one had to be sorry to me you know. But the ones that wanted it, great I’m happy for them. But no one owed me anything. No one owes me, still, doesn’t.

My brother was in jail at the time and I said, “what do you think about that Pete?” And he said, “well if they were really sorry they’d let me out!”

There is a lot of traditional law and ceremony still practised. They’re out there now as we speak. They’ll be happy that they’ve had the rain because the food will be there. But the law still goes on every year. That’s why you got that permit. You got to get a permit to go in through for the land. If you go off the road, $10,000 fine. Because no woman can see men during men’s only ceremonies. When they’re finished they’ll be all painted in blood. It’s alive and well. Yeah, no one knows about it because it’s not spoken about outside our own communities. It is still very much a living culture.