Kimberley Rock Art – Research In Partnership With Traditional Owners

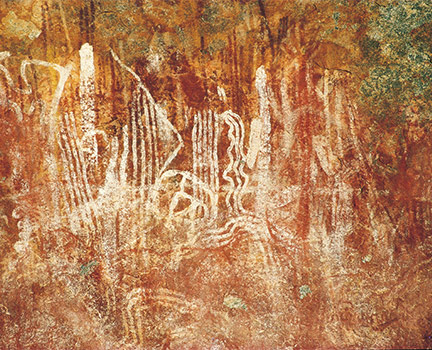

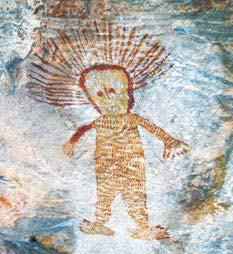

Professor Peter Veth of the University of WA leads the Kimberley Visions project, involving comparative archaeological documentation and dating of early rock art repertoires from across the Kimberley and western Arnhem Land in northern Australia.

In this interview, Peter describes his work with local communities and how they work together to document and protect the ancient rock art of the Kimberley region.

Your work will bring to light rock art galleries unknown to non-Kimberley people. Is your work helping reconnect traditional owners to the work as well?

Yes, we actually do our work now in different kinds of workshops with communities and with the ranger programs. We can do research combined with rock art management. We ask communities about their own priorities. They have a Healthy Country Plan and rock art and heritage is one of those priorities.

We sometimes develop a program that might include trips with the Rangers. We work as part of a bigger programme like an Australian Research Council Grant. Kimberly Visions is another programme we are going to work on. It looks at the values, origins of art, and contemporary values of the northeast Kimberly. We build the questions up from that programme.

The budget pays for consultation with the Rangers and the traditional owners. That’s a significant part. There are two teams who will be doing some filming with the community, including a French team of three specialists. We give plain language reports, films, workshops. It’s a two-way skills transfer as part of everyday work.

That’s what we do. You wouldn’t get to work in the Kimberly if you didn’t do something that was value-adding.

Some of this artwork is in remote places. Is your project helping to reconnect traditional owners with what is there?

Some rock art the traditional owners would be familiar with because it’s an area that you get to by boat or vehicle. Other art might be accessible because it’s part of a mission or station run. In other cases, they wouldn’t have had the chance to go back. This is because they wouldn’t necessarily have chopper access or supplies to access an area. In those cases, we can help people get back to visit traditional lands and manage the art that’s there.

That must be quite significant.

Yes, it’s huge. I think only a small proportion of the total art repertoires would still be visited by the traditional owners if that. Even the Rangers wouldn’t necessarily get a chance to go back to the coastal sites that the tourism operators might target each year. The Rangers are fortunate if they have the time and provisions to get back to visit these sites, manage values and carry out cultural recording.

How are these initiatives supported?

The Australian Federal Government currently puts $93 million into Indigenous Protected Area Programmes. Out of a billion dollar Indigenous portfolio budget that’s a tiny percentage. Yet it’s an incredible initiative. It’s successful. They’re lobbying at the moment to try and get that maintained if not beefed up.

The cultural heritage is an important part of that. Indigenous Protected Areas look at all things like natural systems, tourism, waste, up-skilling. They’ve always got heritage in the matrix. However, they’re usually run within a natural resource framework. These are highly skilled people but they may not have had the chance to do heritage training. So it tends to be teams like us coming in that can actually start working in collaboration to build that capacity.

Kimberly people know that the rock art’s there as it’s been there for as long as they’ve been there. How do they respond to your work? Where do they see the value coming from?

Historically, the value of research to the local people has been patchy. Some researchers have had long relationships and they’ve helped in management and site protection. Others may have done it more for pure research and may have given the traditional owners only limited feedback. Some people go in as bush-walkers, increasingly with consent but sometimes without any consent. Over the years some people have published some highly speculative and sometimes inaccurate material which has usually been challenged by traditional owners and committed researchers.

So there are legacy issues throughout Aboriginal Australia which still needs to be addressed. I was the consultant to an ABC film series First Footprints– this was a unique programme. It addressed that issue and provided a vehicle for the community to speak for their country and heritage in both traditional and scientific terms.

It reflected the kind of collaborative work that now generally happens. Generally, the uptake by communities is very good when they have involvement in crafting the research priorities.

Is there a good history of collaborative relationships?

Yes, but only if there is control and if communities have their own management. If they’ve had what is perceived as inappropriate things written and said about their culture, communities are naturally very concerned. Communities want to prioritise research and management work with skills transfer that helps their young people. This assists in keeping young people out of harm and builds up the skills base in the community.

Communities don’t want to see white researchers simply hoovering up data to become cleverer. They want to see a genuine knowledge economy built up on the ground. That is how it should be.

Are you seeing any interest from indigenous young people?

Yes, but it’s variable. Pretty well everyone is digitally literate and using lots of electronic tablets and devices. They are interested in the work that’s going on. Some people want to go out and do intensive work and others want to work more on natural resource issues, like fire management.

Some people have come off serious cycles of harm. They’re going out bush for long periods possibly for the first time. We usually work in mixed teams with people bringing different levels of background skills and interest in cultural mapping. On the Canning Stock Route, where I’ve worked with communities for 30 years, they’ve gone from no Rangers to 100 on the payroll, and up to 350 working with Kunyirninpa Jukurrpa. It’s a serious success story.

What do these Rangers do?

Again it depends on their corporation and their own Healthy Country Plan. The expectation is that they would look after the health of the country. If there’s a bad fire regime they might try and burn in a way that assists habitat variety and protects rock art sites.

This, in turn, helps endangered animals. They use incendiary bombing schemes and on the ground burning. They do that throughout the desert and in Kimberly. They do feral pest control. They cut vegetation away from sites where high-intensity fires might destroy the art. There have been some catastrophic fire episodes. Some fires have destroyed galleries that were thousands of years old. The prevention of that damage is important work.

The Rangers also do cultural tourism. They check the permit systems depending on where they are. They make sure that all drivers and tourists are observing cultural and camping rules. They have the power to issue tickets on the Stock Route.

Are you saying art and cultural protection is part of the Rangers portfolio?

It is and it should increase. They want it to increase. They, of course, have both traditional and hybrid views of what that culture should be and is. The skill base is around how you’d record it for monitoring purposes and enjoyment by the wider community. There is a need in managing these assets in the systematic photography and 3D mapping. This data can stored in a community database – knowledge centre – and mirrored elsewhere. That’s something some communities have and others don’t and generally, they want it. We are interested in that traditional knowledge base across the landscape. That’s why we always work closely with these ranger teams and their representative bodies.

Can you describe the active role Kimberly people are taking in managing their cultural estates?

The Kimberly Land Council has heritage officers. They have the Indigenous Protected Area program under their umbrella. It’s funded by the Australian Federal Government. They have Healthy Country Plans and they visit and maintain sites. They try to ensure that they’re kept in the best possible condition. There are also businesses like Wandjina Tours based out of Freshwater Cove. Danny Woolagoodja and Robyn Mungalu are two of the traditional owners of that country.

They visit sites and people like Donny repaint some of them. They have cultural tourism and sometimes significant numbers of visitors come in through the boat cruises. The traditional owners have particular trails they take visitors through. They have an Arts Centre there and they sell artwork directly to visitors. If you go to Wijingarra Bard Bard, Freshwater Cove you’ll actually see serious art collections. Visitors buy $1,000 – $3,000 paintings and get back on their boats. They might go up the coast and visit Raft Point and see some important art sites up there by boat or by chopper with traditional owners and Rangers.

That local community has got a pretty good economy happening. The rangers are involved in managing traditional owners’ arts. This is part of The Dambimangari Corporation based in Derby.

But these are still early days. If we’d had this discussion maybe ten years ago we’d have been talking a lot less about initiatives on the ranger front across the north-west. It’s come a long way in ten years which is fantastic.

International Partners

The Centre for Rock Art Research and Management at University of Western Australia has global alliances with:

- Getty Foundation, United States of America

- Centre National de Prehistoire, France

- University of California, Berkeley

- Pennsylvania State University

- Rock Art Research Institute of South Africa

Image Usage: images are being used with the permission of the copyright owner. Please do not copy or reproduce these images without obtaining permission. Wandjina® is a registered trademark of the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre.

Aboriginal Rock Art Article Series: