Jimmy Pike’s Art In The Market Place

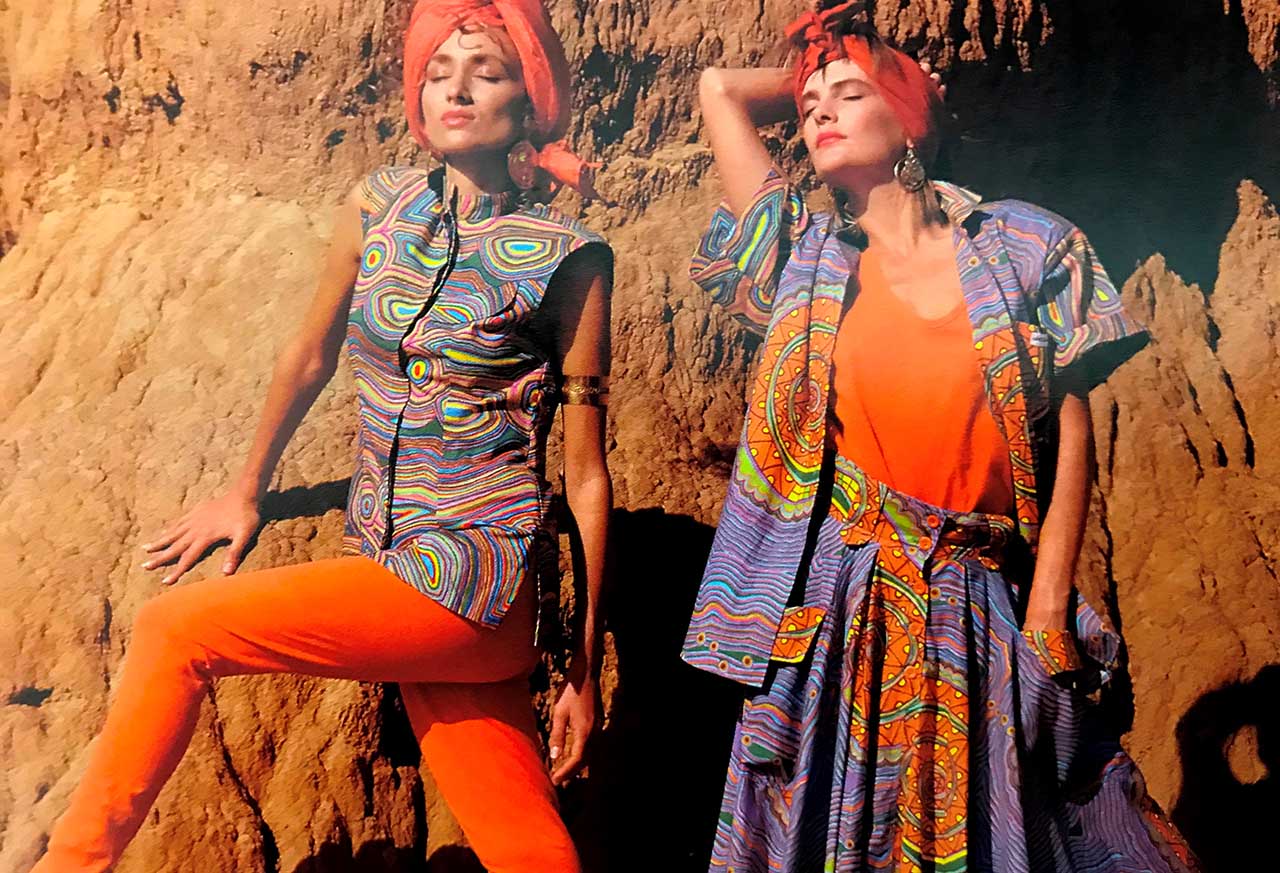

The commercialisation of Jimmy Pike’s artwork onto lifestyle products in the late 1980’s was part of a much bigger design movement in Australia. There were quite a few other artistic figures who were giving us an Australian identity on everyday items, taking Australian design onto products that we wore and we carried with us. Names like Jenny Kee, Ken Done, Reg Mombassa at Mambo, John Moriaty at Balarinji and Jimmy Pike at Desert Designs, all set about transforming the street level design world around us.

It was art-based, and people wore it in a general sense. It was quite Australian in its identity. That was really important. It was an era when Australian movies and Australian music were consolidating their credentials, Australian art had set up some degree of semi-modernist credentials. Then there was emerging work that was used on everyday objects.

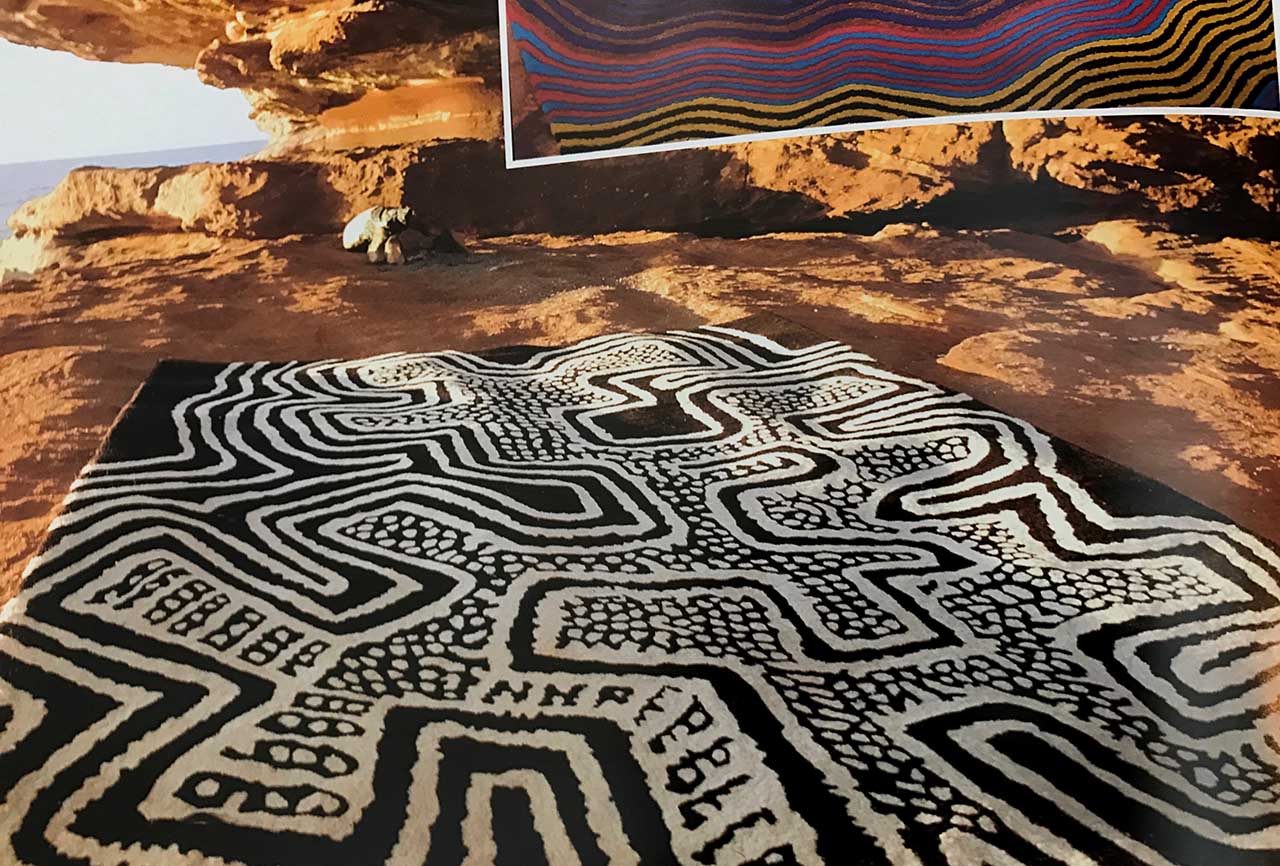

This Australian lifestyle use of artwork started to include Aboriginal designs. The important thing at that point was that Aboriginal art could cross over into the contemporary Australian design world.

It was a really big jump to make, and it was being made on lots of different fronts. Aboriginal design crosses over from being purely an ethnographic and anthropological form of knowledge, one that doesn’t belong to modern Australia, into something else. It previously had its identity only in an Aboriginal world, and the wider group of white Australia couldn’t really have any association with it. There were no connection points.

Jimmy Pike’s artwork did appear on fashion items, kids clothing, tee shirts, silk scarves, home textiles, men’s ties. There was this kind of conversation going on between the Aboriginal artists and the wider audience.

There were people who thought it was inappropriate that an Aboriginal artist’s work would appear on clothing and accessories. Even at that time in the mid 1980s, there was a sense that Aboriginal art had to be kept separate from Western art, from Australian art generally. Everything about Aboriginal cultural accessibility had its own set of parameters, and some felt that it was never going to have a connection or a role in mainstream society.

This type of conversation wasn’t that interesting for Jimmy Pike. He created the art, occasionally he made statements, although generally it didn’t interest him. He was interested in being an artist. He was interested in people liking his work, and people recognising his role. He remained very much the artist in the studio.

He gave permission for how his work was used. He held copyright ownership of his artwork on everything that went out. He was licensing his art in the same way that any other artist in Australia was licensing artwork. He could decide if artwork was appropriate, was used suitably, was fitting all the criteria, and all of that was set out in legal contracts.

The main boundaries that were set in the contracts were around the issues that the art and its applications couldn’t include culturally sensitive material from Jimmy Pike’s perspective. That was still a whole area being worked out, even in the 1980’s. Decisions were being made in traditional communities about what aspects of Aboriginal culture could be discussed in the open, in the public domain, and what couldn’t.

Occasionally, there was one or two instances where other Aboriginal people from Jimmy’s group felt that images that he created were too exposing of a particular aspect of their culture. People weren’t comfortable with those images being in the public domain. In those cases they told him to withdraw it, and he withdrew it. Regardless of where it had got to in the process.

I think that this type of conversation was one that people who were working closely with Aboriginal groups were very familiar with. That was because one of the first things that happened in the early 1970’s, was that those very senior men had to decide what they could reveal in a painting. They were deciding on the appropriate level of information that could be communicated in a public artwork.

If a map was getting too specific then if wasn’t suitable for the public to see. If someone in the tribal area wasn’t permitted to see it and you put it in the public domain, and therefore it was possible for them to see it there, you had crossed a kind of line in your own culture that could be really troublesome. A lot of those discussions had been going on for more than 15 years by the time Jimmy Pike came to those same sorts of issues.

Some communities were still living very, very traditionally. Others were living in urban groups. The people who were living traditionally had ideas that were much more conservative in terms of how much interaction they wanted to have with the larger world. The parameters were much tighter.

The general public didn’t have a deep understanding of the background information that went with an artwork. Mostly they saw it as a graphic design with clear Aboriginal connections. They might sense the energy of the work but not fully understand all that the symbols mean. You might see a power in the work, and feel that it must have had a strong meaning for the artist, but you won’t be able to fully relate the story behind it. This is different for Aboriginal people in each group because the symbols are recognisable and they understand the story and where it comes from. There are other cases where certain symbols would only be meaningful and important to a small group within that community.

As an artwork comes further away from its origins with Aboriginal people into the wider Australian world, it remains very much a symbol that comes from a specific group of people. Hopefully it shows their culture and the depth of their feeling for their country, or depth of feeling for their whole history, but it’s a graphic artwork. The information that comes with it is, at one level, important. At another level, the artwork and the meaning can be separated. The art can communicate very powerfully without words or explanation.

Read More: