How Aboriginal Colours and Group Art Styles Develop

Do you sometimes recognise a painting style or colour palette and think of a particular Aboriginal community?

In this article David Wroth talks about how Aboriginal communities developed their own visual language and colour palette through group interaction. The decisions of each group influenced the development of the style of painting that may be identified as belonging to that specific community or region.

From the 1970's the contemporary Aboriginal art movement developed in communities across Australia.

These styles and colour palettes have developed through a fascinating decision making process. Aboriginal art communities often work together in groups, and decisions about how elements are represented are often made after considerable debate. Colour choice is also often arrived at through a group decision making process.

There might be one or two strong individuals who will be keen to innovate. They will argue their case and often lead the group into new ways of representing story elements. They might also persuade the group to expand the colour palette that can be used by the group.

Some communities agree to paint within a traditional colour range, some choose a limited palette combining traditional colours with a couple of others. There are other groups who have permitted their members to paint from a broad palette. The availability of full colour charts has given groups more choice and many senior artists have embraced that choice.

Communities Develop Styles And Palette

At the beginning of the contemporary art movement Aboriginal people didn't have a set of rules about the use of colour. They had very set information on the structure and meaning of the subject matter but the artistic style or the use of colour was not set. These elements have evolved over decades. There are now regional characteristics that have become recognisable.

These painting styles have formed as a result of people within a community coming together and painting together. Painting issues have been discussed and resolved at a community level as the painting movement progressed in each location.

Symbolic Design Taught to Lorna Fencer

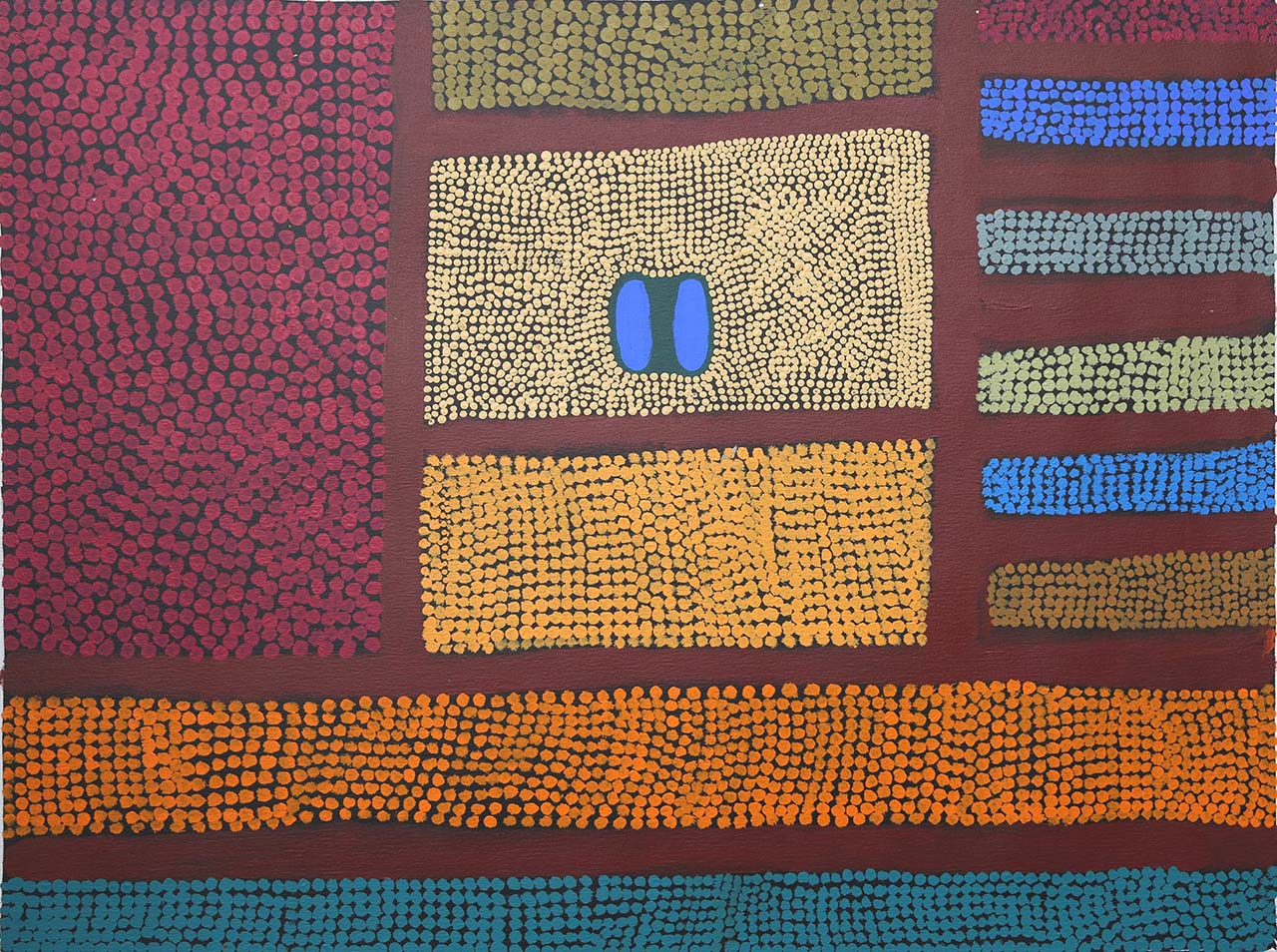

There is a story from the community of Lajamanu that shows how a style may have originally referenced traditional painting. This style was then challenged by an individual artist seeking to develop her own ideas. Lorna Fencer was told by her peer group of artists how to represent symbolic designs. They had to be painted in black and the dotting that went around the design had to be white. The meaningful symbols were always surrounded with the white dots.

Individuals Argue For Change

Lorna Fencer argued that she wasn't bound as an artist to continue to paint the symbols as they were used traditionally. A considerable argument went on between the elders in the studio. One group insisted that you can't change traditional ways of placing colour in certain circumstances. On the other side a group supported Lorna by saying that she had the right to change the nature of colours. This was resolved and Lorna went on to use a broader colour palette in her paintings.

Conservative Thinking Had Kept Traditions Alive

Decision making in Aboriginal culture has tradionally been quite conservative. This meant that stories could be passed on from one generation to another in a mostly unchanged form. The ceremonies and the initiation processes also follow very strict guidelines. This discipline ensured that there was continuity of knowledge from generation to generation.

Collective Decision Making

As artists took on the painting process they had to arrive at their own way of expressing the power of the subject matter they were dealing with. They made changes if they saw it as appropriate and often they had to argue the case with their peers. Some communities have chosen to stay with using traditional ochre pigments from the earth. These are red ochre, yellow oxide, white pipeclay, and black charcoal. There's quite a number of painting communities that specialise in expressing all their stories using those valuable materials.

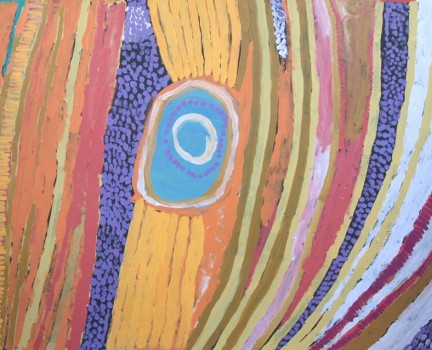

The Balgo Artists Change of Palette

Many communities started off with the traditional colours and moved on to a broader palette. The artists of Balgo are a good example of such a group. Balgo is a small Aboriginal community that connects with both the Great Sandy Desert and the Tanami Desert. The early paintings from Balgo in the mid-1980s used a lot of black and brown with a little bit of yellow and white as highlights. It was a very austere colour palette that they started with. At some point they decided to embrace all the tones of reds and yellows and maybe pinks and introduce blues and so on. Over a five or ten year period the art from that community was transformed.

Artist Groups Work Together

In artist groups you often see strong individuals taking artistic directions and that sets a trend for a certain period of time. You see these powerful influences facilitate change in their group. As Aboriginal art is a process separate from traditional ceremony it has been able to develop fairly quickly. This has occurred in a shared way. Artists mostly choose to paint together in large groups and ideas quickly get absorbed, discussed, worked out, accepted or rejected, not just by one person working alone in a studio, but by ten people all looking and seeing.

If something is successfully expressed about a story then that can benefit ten artists all at once. Nobody seems to feel that every innovation entirely belongs to them. This collaborative way of working has brought very rapid development at a group level by artists working together. To some degree that forms the collective style because people work together and influence each other.

The Broader Palette

Over the years art co-ordinators have had access to artist colour charts that show the full range of paint colours available to purchase. In the early days artists would probably work with six or eight colours. They would usually order those colours every time. The colour charts have given many artists an opportunity to see what is available.

I've heard of a very important artist being shown the colour range of 30 or 40 colours and they've been asked "Which colours do you want for your painting?" Famously, the artist ran their hand over the whole chart and said "I want the whole lot. Whole lot, give me everything."

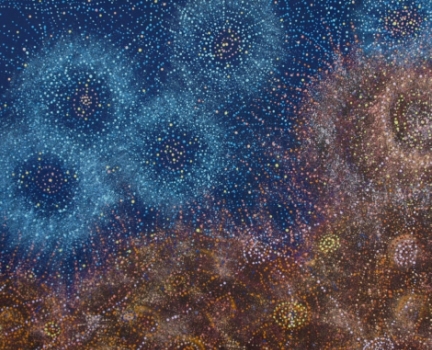

These are clear statements that the artists no longer want to be limited to the earth colours or a limited range palette. They want the whole palette. They want a purple or three blues and four reds. It seems that once artists could see that the paint chart that showed all the opportunities for colour, they started thinking more broadly.

Rapid Innovation in Groups

Once strong individuals made statements about using a wide range of colour then that opens things up for a group. The most influential aspect of style is people's adaptation of colour into traditional designs. Once an individual makes some strong statements, other people tend to to say, "Yes, that works really well." Sometimes this process can condense ten years of artistic endeavour down into six months. This has led to the most extraordinary progress in terms of people making very powerful statements about their culture, because it has influence to the power of ten. These groups might have ten artists who are working together and one discovery is not one discovery for one person; it's a discovery for all ten. As that builds it becomes one of those algorithm expressions, a curve of innovation.

Times of Transition

Something seems to happen when senior artists cease to work. Perhaps they become blind or they become encumbered and they can't paint with their hands. It might be that they become just too old and frail to paint. There seems to be a capacity for the next generation of family members to take up that work. They might have been watching that elder painter for ten years. They may have been painting themselves but they've been a bit restrained in what they're doing.

Once the mantle gets passed from a senior artist to the next in line, it's almost like they've served their apprenticeship. They've watched, they've absorbed the knowledge, they've absorbed all the practice information they need about creating the paintings. They are then freed up to explore those stories and bring new energy to them through their paintings. There is a respectful way that these transitions occur. It reflects both the high regard for elders and the non-competing way people in these communities approach their art.

Read more: