Australian Aboriginal Ochre Painted Larrakitj Memorial Poles

Gordon is a West Australian art restoration specialist. He is both a restorer and collector of Australian Aboriginal ochre artworks. In this interview with David Wroth, he discusses working with ochre painted Larrakitj from Arnhem Land, the ephemeral nature of ochre and his thoughts about its future.

Q. You've done work for the people from Yirrkala?

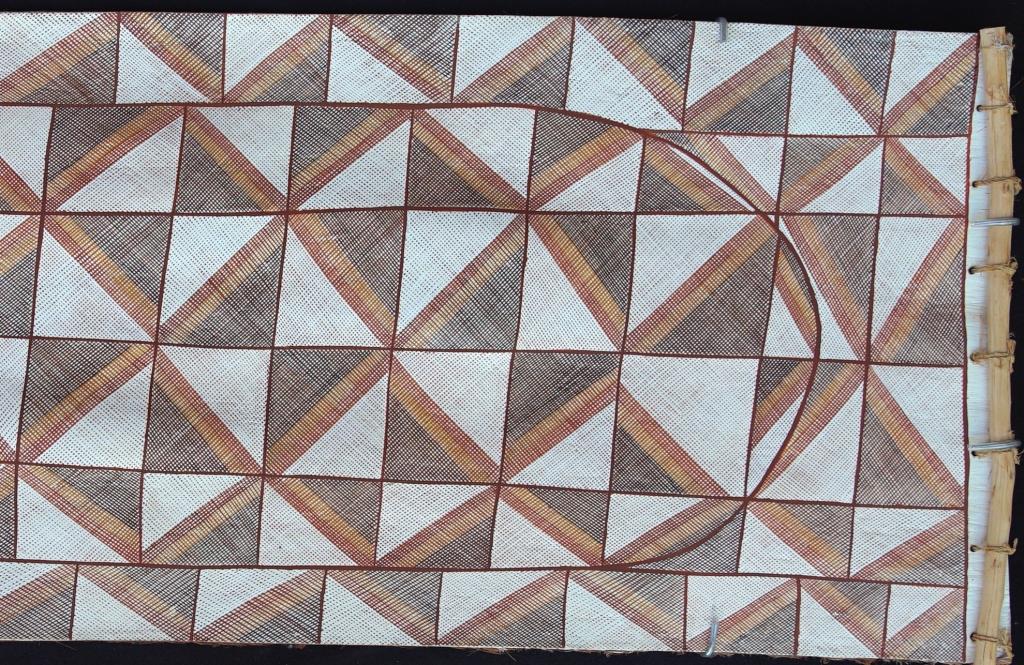

I've worked on a lot of Arnhem Land art. I worked on a show, Larrakitj. A lot of Larrakitj, which are hollowed out stringy bark logs, which are painted with ochres. They were designed as coffins. I worked on a lot of these that were made by the artists in the Yirrkala community.

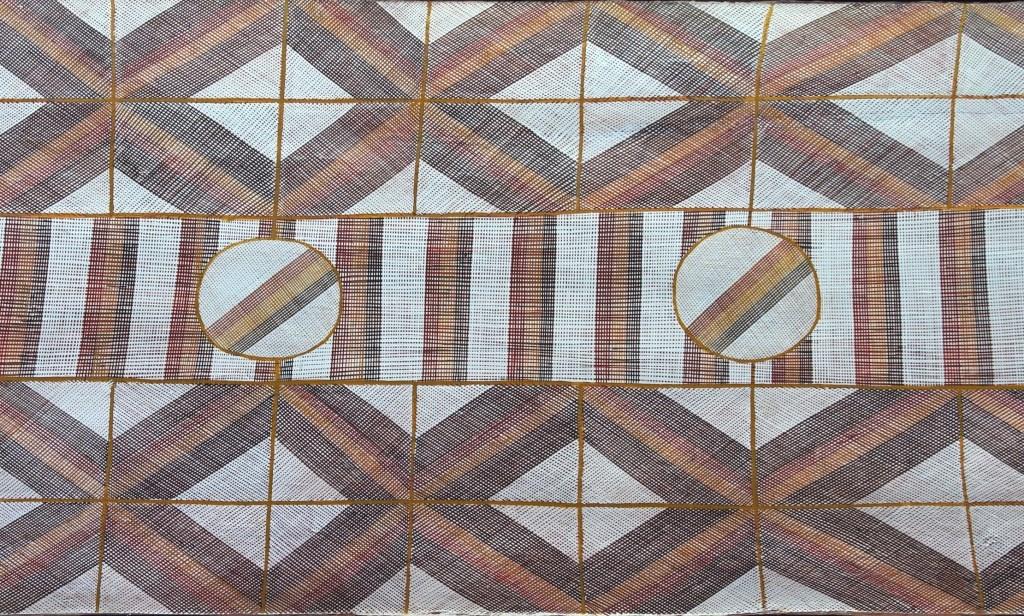

One thing I did learn is that each artist has a particular way of applying their design. Their design is, in a way if you think in European terms, a form of copyright. When you are looking at a beautifully decorated pole, you see the countless hours that go into producing these wonderful things. Some lines with a slight curve, some lines which are straight, some lines with a small squiggle. These are very important; they denote particular groups, family groups who are working in that art.

Larrakitj Were Originally Coffins

The Larrakitj were originally made as coffins. They were hollowed out, they were decorated, not unlike grave-posts, except in this case, in the Larrakitj, the body of the deceased was burnt, and the bones were broken up and put into these Larrakitj. Then they were displayed, and their spirits stayed within the community.

I did work for an exhibition on Larrakitj poles from the Kerry Stokes Collection. We came across an old photograph of an ancestor of one of the artists we were currently working with. It showed him as a young child crushing up the bones of this family member and putting them into the Larrakitj pole. The pole was beautifully created. It is designed to sit there and blend back into the environment.

The Ephemeral Nature of Ochre

Q. One of the concerns of people when they approach Aboriginal ochre art is about the ephemeral nature of ochre. What do you say to people about those concerns?

I get cranky, to be honest. The last people I would have advising artists on their creativity are conservators or restorers, because we tend to put up so many high hurdles. You have to understand that, yes, ochre works on bark or on canvas are ephemeral. So is a whole lot of White European art; you'd never buy a Vincent Van Gogh if you knew what happens to the yellows over time. You'd never buy a lot of Australian contemporary paintings like a Jenny Watson if you thought that way.

All contemporary artists work with the materials they've got. It's not the role of the conservator to be telling, dictating, or even influencing how artists select their materials. Our involvement is just to make these things last and be as close to what they were and pleasurable for as long as possible without changing them.

Ochres are ephemeral but managed correctly they are fine. If you hang your 1960s or 1970s ochre bark painting out in the garden, then yes it would fall to pieces. You need to manage these things like you would manage anything that's beautiful. An art piece, something of a human spirit, you just have to look after them.

Fortunately, nowadays, we have the technology where we can help prevent these things deteriorating too rapidly. I certainly want to put to bed the notion that one wouldn't buy an Indigenous painting, an ochre on bark because they're earth colours and they may crumble. Pretty well anything we produce in the 20th century now, with our technology, is also fairly ephemeral. The key is caring for these beautiful pieces and attending to minor maintenance if and when it needs it.

Q. Before the 1970s and the rise of the Desert Art movement, ochre Aboriginal art was what most Australians knew. The world knew Aboriginal art through ochre painting. Where might it go, do you think, in the future?

I hope it's retained as a living art form. I'm not just purely a restorer of Indigenous art; I repair a lot of fairly high-level European art. This experience has taught me the value of older art forms. It's all part of the history and the tradition and the story of the creative spirit. I hope we don't dispose of these approaches to art because we think we've got something newer or synthetic, or something that will outlast and is better because we've made that mistake so many times.

In the 1970s when I worked with archival documents, we used a type of nylon encapsulating material for old documents. This material had been in favour since the 1950s but later we had to go back and untangle an enormous mess because the nylon had degraded. There is something nice about weathering and getting a bit old. Same with ochres, you live with them, they have the look of time on them.

As long as you're sensible with ochre artworks, they are as durable and as preservable as most Australian contemporary work that I've seen. It's just a case of good management and choosing a place to hang them away from strong light, steam and heat.

Read More: Australian Aboriginal Ochre Painting

[ssba]