Yuendumu Men’s Museum and Western Desert Art

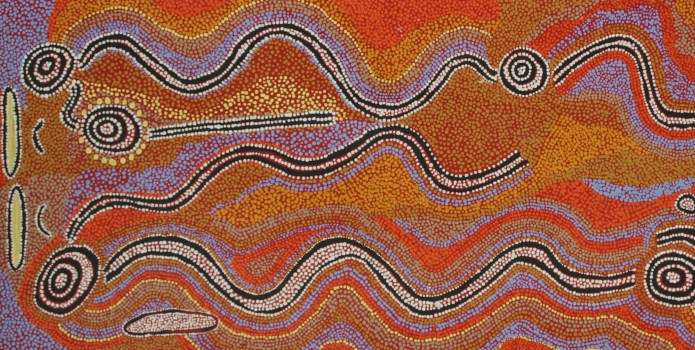

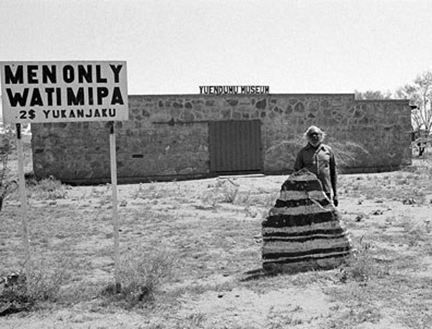

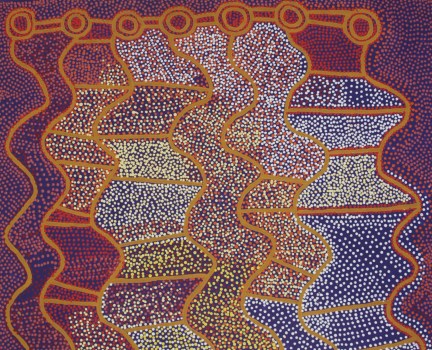

In 1971 at the Warlpiri community of Yuendumu, north-west of Alice Springs, the senior men established a Museum as a safehouse for storing culturally sensitive items and artefacts used in ceremony and Law. It also contained murals and sand paintings representing significant Dreaming stories from the various Warlpiri skin groups, comprising images from sacred sites located deep into ancestral lands.

In September 2015 the historically significant museum was re-opened and the record of its initial concept was re-examined. The year of its original creation is of course highly significant in the story of contemporary Aboriginal art. 1971 marked the time when senior men at a neighbouring community of Papunya painted their first murals based on Dreaming stories, and proceeded to make the individual paintings that began the rise of the Western Desert art movement.

Yuendumu elder Harry Jakamarra Nelson, who was a young man when the museum was opened 44 years ago, described some of the intention of the senior men at the time. "Instead of Old Men taking their young fellas out there and showing them the paintings and the stories associated with that particular place, they decided to build a museum."

Thomas Jangala Rice described the process – "People from the east, north, south and west all came together here and talked a lot about establishing the museum. Long before the museum was built they talked about it quite a lot. Proper consultation, the different groups, the different moieties."

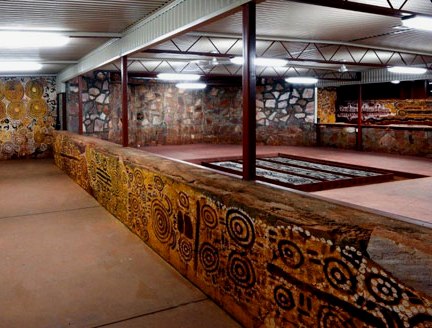

The process as it occurred at Yuendumu was towards a specific outcome, managed entirely by senior Aboriginal men. Items of a secret-sacred nature were housed there, with restricted access to the museum and its contents. These items included the sacred cave paintings that had been reproduced in mural form, and sacred objects housed in locked cabinets, to be seen only by the correctly appointed men during ceremonial events. The museum was oriented in such a way that the murals and hidden sacred objects were aligned towards the country that they belonged to.

Initially, outsiders could visit the museum, it had a role as a showcase for ceremonial culture, although uninitiated young men from the region could not enter. A senior man, Darby Jampijinpa Ross, acted as museum supervisor, but as he became frail with age, younger men were required to help out. At some point during the late 1970s a breach of cultural security and authority alarmed the Elders, and they removed the sacred objects back to safekeeping places on Country, to be reclaimed only at ceremony time.

So the 2015 re-opening of the Men’s Museum marks a full turning of the story. Murals were restored and important cultural material was re-instated. The importance of art to the whole community at Yuendumu reflects the interaction that the community has had with the Aboriginal art market over a 30 year timespan.

Perhaps the story of the Men’s Museum indicates why the cultural impetus that fuelled the growth of the desert art movement also gave the paintings a level of independence from the strict cultural laws that surround objects that are primarily ceremonial in nature. The story of the Yuendumu Men’s Museum has now been published in a book by Philip Jones, curator from the South Australian Museum.

Read more: