David Downs

David Downs - Walmajarri Artist, Great Sandy Desert, was custodian for Kurtal Rainmaker Story

Jarinyanu David Downs (1925-1995) was born in Walmajarri country in the Great Sandy Desert but lived the greater part of his life in the Fitzroy Valley region north of his homelands. When he began his artistic career in the 1980s he drew heavily on the strong desert culture that had moved with the emigrating people into the Fitzroy area. In this sense his artistic career was analogous to that of Rover Thomas who also came from desert country to the south, but was to have a strong influence on Aboriginal art developments in the Kimberley.

Jarinyanu David Downs moved north from his traditional Walmajarri lands to the cattle station country of the Fitzroy Valley in the 1940s. This was seen as an exodus time for the people of the desert, when whole families moved to the settlements and the critical population of desert areas dwindled to unsustainable numbers. The large community of desert people from Wangkajunga and Walmajarri groups maintained strong cultural practices in the Fitzroy Valley and continued to come together at ceremony time to perform the rituals and manage the social arrangements that were dealt with at these times.

Like many of his countrymen, Jarinyanu David Downs worked as a stockman on the cattle stations. During the 1960s Jarinyanu David Downs made his first artworks, designs on traditional artefacts, then around 1980 made his first paintings. In Fitzroy Crossing the United Aboriginal Mission had worked with Aboriginal people since the early 1950s and many of the desert lawmen and later artists had close ties with the Church. Jarinyanu David Downs painted many religious paintings and came to incorporate symbols from both Christian and traditional law practice from the desert. As part of these symbols Jarinyanu David Downs found ways to represent Ancestral beings with a human form, thus giving visual concept to what was previously unseen from the Ngarrangkani Dreaming world.

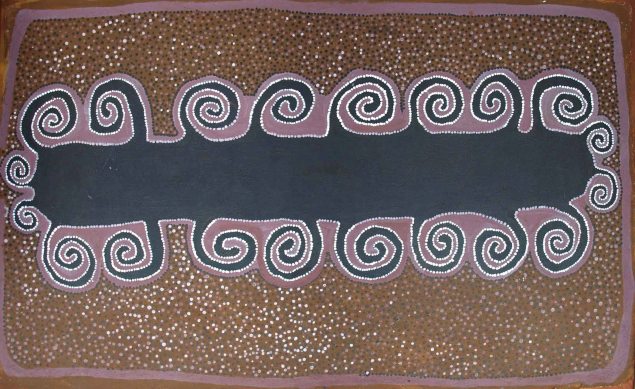

The image of the Ancestral spirit Kurtal became closely identified with the artist and custodian Jarinyanu David Downs. Seen with some of the many headdresses showing the different stages of the storm, Kurtal wears full ceremonial dress with painted body markings and pearl shell ornament.

Jarinyanu David Downs was one of those old cowboys who, like Rover Thomas, was born in the Great Sandy Desert in the 1920s and eventually, towards the end of their lives, settled in the Kimberley region in the north-west of Western Australia. Jarinyanu first moved from his traditional lands to the cattle stations in the 1940s while still in his early twenties, to join the family of his promised bride. The next twenty years were spent droving cattle as well as occasionally working in the gold mines around Halls Creek. Jarinyanu’s first European boss bequeathed him his European name, David Downs, however, when he eventually settled in Fitzroy Crossing due to its proximity to the Wangkajunga country of his birth, he reverted to using his real birth name.

Jarinyanu David Downs first began working as an artist after moving to Fitzroy Crossing in the 1960s, decorating boomerangs, shields and coolamons. However it wasn’t until 1980 that he was commissioned to work on paper and canvas, using traditional ochres with natural resins as a binder. These initial works were typically dramatic dark silhouettes against a white acrylic background.

Pictorial symbols were used to represent country, and although figures appear, they were merely one element within a larger composition, in contrast to the dominance of the figure in his later paintings. The influence of Christianity could be seen from the outset in many of his earliest works.

As Jarinyanu’s career developed he developed a visual language that expressed his Christian beliefs coupled with a celebration of traditional law. He believed that as god created the natural world, it was perfectly acceptable to pay homage to his creation of the surrounding environment in accordance with its local cultural form. In doing so he created a relationship between Australian Christianity and specific cultural sites, which white Australia had neglected to identify. At the same time, he daringly depicted ancestral beings in human form, visualizing the once unseen Ngarrangkani (Dreaming) ancestors.

The primary vehicle for expressing this two-way religious philosophy was the song cycle of

Kurtal, the ancestral rain man. He was born on a distant island and traveled to the Kimberley as a cyclone. As he moved on inland he created places of ‘living water’ (permanent water sources) and visited other rain men, occasionally gaining valuable items from them through trickery and magic.

The figure of Kurtal, often depicted with ceremonial headdress, and the participants in ceremonies relating to his story, appear constantly in Jarinyanu’s work. Other than his occasional canvases depicting Christian themes such as Whale Fish Vomiting Jonah 1993 and Jesus Preach’im All People 1986, it is the Kurtal figure that filled canvas after canvas until his death in 1995.

Jarinyanu’s success at bridging two such separate cosmologies can be seen as part of a broader tradition of cultural exchange in the Kimberley, predating European contact. However, it is a sign of great triumph that his contact with Christianity did not weaken his commitment to ritual law. He was very conscious of himself as an artist. ‘I’m different’ he would claim, when describing himself. His peers would describe his directness by exclaiming, ‘he’ll tell you right out’ (Kentish 1995: 2) He had come to terms with the concept of individual fame brought keenly into focus by viewing his own work in art galleries, and the experience of having his portrait painted and hung in the Archibald Prize. His ability to negotiate his way in the white world no doubt had great influence on his success. He was one of three Walmajarri artists at Fitzroy crossing who began painting on canvas through private representation as individual artists.

Jarinyanu, along with Peter Skipper Jangkarti, was represented by Duncan Kentish, whilst Jimmy Pike whose career began in Fremantle prison in 1980 was represented by Steve Culley and David Wroth of Desert Designs. Individual representation brought many rewards, particularly solo exhibitions in galleries such as Bonython-Meadmore Gallery in 1988, Roar 2 Studios in 1991, Chapman Gallery in 1993, and Ray Hughes in Sydney in 1995, where always resplendent in his white shirt and pants, he was presented as a contemporary artist, alongside non-Indigenous artists.

Jarinyanu David Downs enjoyed a highly successful career encompassing sculptural artifacts, painting and a significant body of limited edition prints. He was one of the earliest Aboriginal artists to be individually represented and, at the time of his death, was considered one of the leading lights of the contemporary Aboriginal art movement.

Profile References

Ryan, Judith. 1993. Images of Power, Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley. Melbourne. National Gallery of Victoria.

Kentish, Duncan. Oct 1995. Jesus Country, in Mount Gambier: The Southern Explorations of David Downs. Adelaide. Duncan Kentish Fine Art.