Timor Carvings

Gallery 2

14 February – 26 March, 2014

Timor island, in the Lesser Sunda Islands, has a long history of influx of populations going back to the early 1500s when Portuguese traders set up a base there while trading sandalwood. Dutch traders working the spice trade arrived in the early 1600s and set up on the western end of the island. Further influxes of Indonesian Malay settlers along the coastal areas in later centuries saw the predominantly Melanesian Aboriginal people of Timor move inland to the more mountainous highland country.

Amongst the Aboriginal inhabitants traditional practices of Animism and Ancestor worship predominate. Each village has a sacred house with a custodian priest and a surrounding taboo area. Because of former coastal warfare, villages and isolated houses are surrounded by stockades, and houses are usually raised on piles.

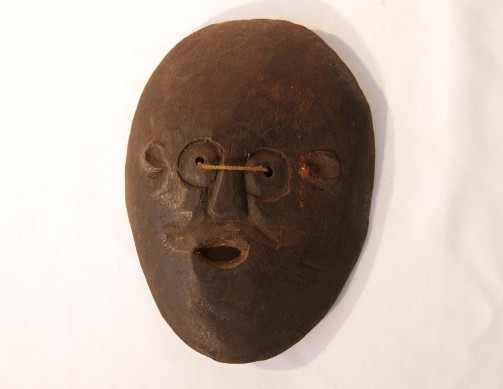

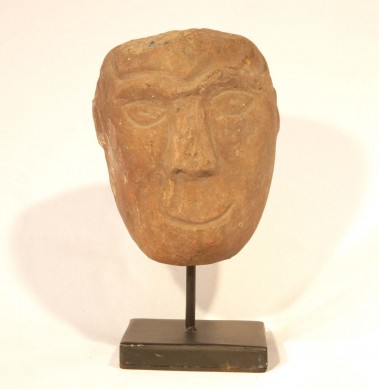

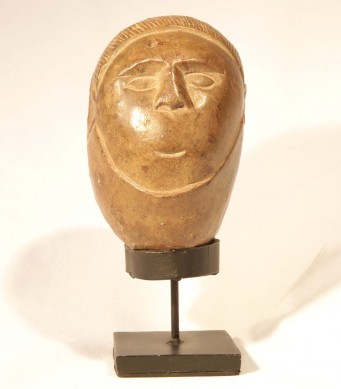

While subsistence farming is at the heart of traditional Timor economy, local craft manufacture of cotton cloth, finely woven fabrics, woven and patterned baskets, forged iron weapons and tools, brass ornaments cast by the lost-wax process, and carved sculptures and masks are specific to rural villages. Here the practice of Animism, or nature-worship, is incorporated with the carving of ancestral statues and masks, which have a ritualistic function.

Dancing, singing, costume and musical ceremony (using gongs and drums) are all used to celebrate or ask for help from the deities. Some occasions that call for these ceremonies may include to ask for successful crop planting, for prosperity, for good weather for the spinning of cotton, for the smooth running of village or regional affairs, for weddings and other celebrations, and for the offering of friendship and reaffirmation of allegiances through royalties or tribute along with the ever present betel nut.

Ancestral figure carvings are produced to honour the departed, and statues are carved and usually kept in the false roof of the lopo. They can be brought out to re-tell stories and as a means to remember past family members. Similarly guardian spirits, ancestor figures or totemic spirits are all captured in wood, to be passed down for posterity and used in order to build the spiritual power of the village.

The tradition of tribal art carving has been continued and is practiced by males exclusively. A collector’s estimate suggests that there may be 60 carvers spread throughout Timor. Virtually no carving or weaving occurs in the few towns in Timor – it remains a very village or kampong activity. The majority of carvings originate from the Belu district of Central Timor. The carvers work with local resources such as wood (teak, red cedarwood, eucalyptus and palmwood), bamboo, coconut shell, gourds, bone and fossilised coral.

Other examples of carving crafts include betel nut containers, walking sticks, spinning tops, oware games, spindles and weaving looms, masks, statues of Guardian figures, seats, beds and Timorese doors. Other crafts include jewellery, combs, pots, bamboo food containers, and musical instruments.

island, in the Lesser Sunda Islands, has a long history of influx of populations going back to the early 1500s when Portuguese traders set up a base there while trading sandalwood. Dutch traders working the spice trade arrived in the early 1600s and set up on the western end of the island. Further influxes of Indonesian Malay settlers along the coastal areas in later centuries saw the predominantly Melanesian Aboriginal people of Timor move inland to the more mountainous highland country.

Amongst the Aboriginal inhabitants traditional practices of Animism and Ancestor worship predominate. Each village has a sacred house with a custodian priest and a surrounding taboo area. Because of former coastal warfare, villages and isolated houses are surrounded by stockades, and houses are usually raised on piles.

While subsistence farming is at the heart of traditional Timor economy, local craft manufacture of cotton cloth, finely woven fabrics, woven and patterned baskets, forged iron weapons and tools, brass ornaments cast by the lost-wax process, and carved sculptures and masks are specific to rural villages. Here the practice of Animism, or nature-worship, is incorporated with the carving of ancestral statues and masks, which have a ritualistic function.

Dancing, singing, costume and musical ceremony (using gongs and drums) are all used to celebrate or ask for help from the deities. Some occasions that call for these ceremonies may include to ask for successful crop planting, for prosperity, for good weather for the spinning of cotton, for the smooth running of village or regional affairs, for weddings and other celebrations, and for the offering of friendship and reaffirmation of allegiances through royalties or tribute along with the ever present betel nut.

Ancestral figure carvings are produced to honour the departed, and statues are carved and usually kept in the false roof of the lopo. They can be brought out to re-tell stories and as a means to remember past family members. Similarly guardian spirits, ancestor figures or totemic spirits are all captured in wood, to be passed down for posterity and used in order to build the spiritual power of the village.

The tradition of tribal art carving has been continued and is practiced by males exclusively. A collector’s estimate suggests that there may be 60 carvers spread throughout Timor. Virtually no carving or weaving occurs in the few towns in Timor – it remains a very village or kampong activity. The majority of carvings originate from the Belu district of Central Timor. The carvers work with local resources such as wood (teak, red cedarwood, eucalyptus and palmwood), bamboo, coconut shell, gourds, bone and fossilised coral.

Other examples of carving crafts include betel nut containers, walking sticks, spinning tops, oware games, spindles and weaving looms, masks, statues of Guardian figures, seats, beds and Timorese doors. Other crafts include jewellery, combs, pots, bamboo food containers, and musical instruments.