Iwantja Artists

Gallery 2

31 May 2013 - 10 July 2013

Stockmen artists riding high

Nicolas Rothwell, The Australian, June 12, 2012

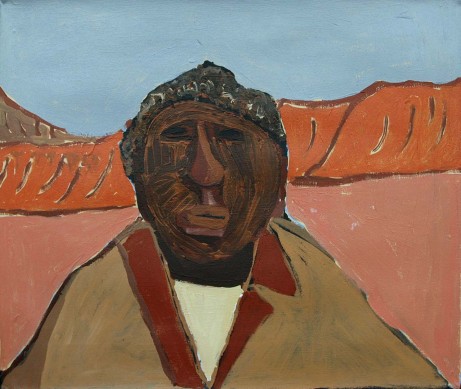

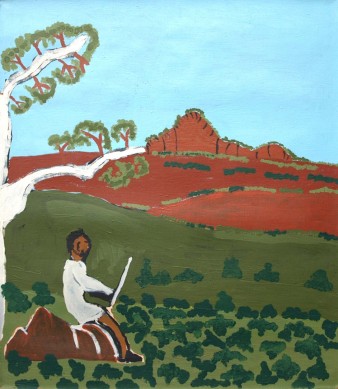

The sun beats down, the wild brumbies seek the shade, the raptors swoop low overhead. All around are sombre flat-topped ranges, maze-like in their interlocking patterns, enclosing sand plains and dry creek beds. Scrub bush, red dirt, dust hanging in the air: desert, but without soft horizons. Harsh country; hard to frame. Such is the landscape stretching on all sides of Indulkana community, a huddle of houses, home to a group of three old stockmen now enjoying a strange new spell in the glare of art-world fame.

Alec Baker, Whiskey Tjukangku and Peter Mungkuri were all born in traditional Pitjantjatjara country and lived out their rich working lives in the saddle, riding on the vast surrounding cattle stations, droving big mobs, ranging as far afield as Oodnadatta and Alice Springs. They were men of skill in that world, kings on horseback. They knew their country twice over: first as desert dwellers, skilled in its song cycles and esoteric stories; second, as the front-line musterers and horse-breakers for Todmorden station, Everard Park and Granite Downs.

Even today, those years fill their thoughts: their talk is laced with memories of the men they worked with: Ironbark Jim Davey, or Ernie Bagger, who kept a tidy camp, and named Tjukangku “Whiskey” after his favourite camel during a long drove out to Tyrone Downs. Even today the three wear their stockman clothes: wide-brimmed Akubras; denim work jeans, checked shirts, dark riding boots with stirrup-ready Cuban heels.

But the cattle years are long since a memory, and life on their small community was less than kind to them until, three years ago, a new wind blew strongly into their world. Indulkana is the eastern-most settlement on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands of the South Australian desert that take their name from the languages spoken there. Its wellbeing has always been an afterthought for the engineers of regional Aboriginal development and economic advancement.

It lies within sight of the north-south Stuart Highway, at the 400km marker south of Alice Springs. The continent-spanning railway runs right past it. Marla Bore, the outpost where Charlie Perkins briefly relocated the southern desert’s administrative capital, lies within easy reach. Naturally enough, given this geography, tourism has always been the plan, and for decades there was a modest arts and crafts studio making trinkets for the pass-through bus-tour trade.

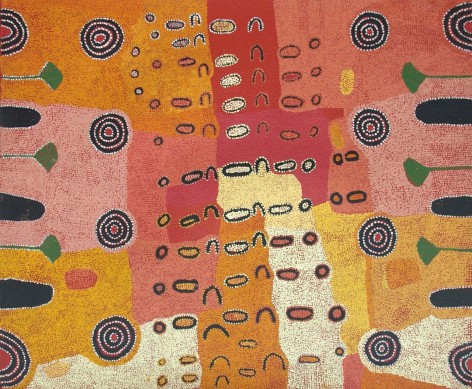

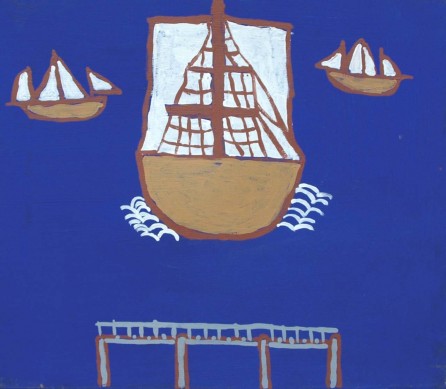

Women worked there: they made the painted seed-pod beads and batiks and woven baskets that were the standard fare. So things went, until, just more than a decade ago, a vogue for paintings by senior men from the Pitjantjatjara lands began spreading through the fine art market. It gained strength. Word reached Indulkana’s Iwantja art centre, which had been brought into the 21st century and made shipshape by a new co-ordinator, Helen Johnson. She gave the men canvas and left them to their devices. What followed was a detonation.

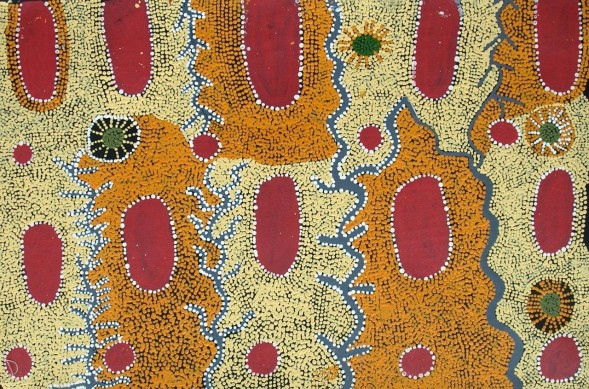

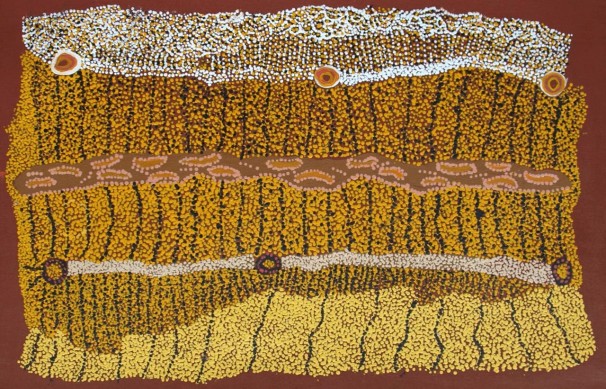

First to paint was Baker, then closing in on his 80th birthday. He soon showed himself to be a precise artist, with a range of themes. Like most tradition-minded desert men, he was extremely wary of revealing sacred knowledge, and was careful to go over his canvases, veiling or painting out any sensitive signs or symbols.

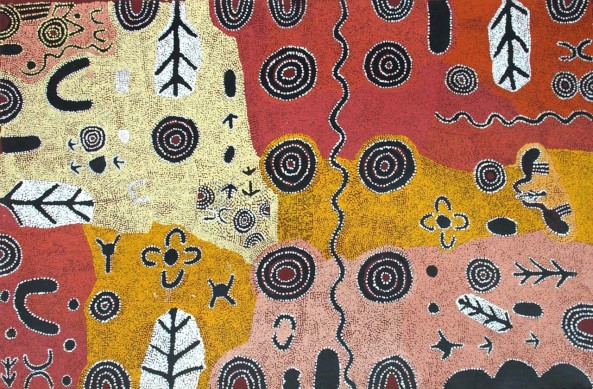

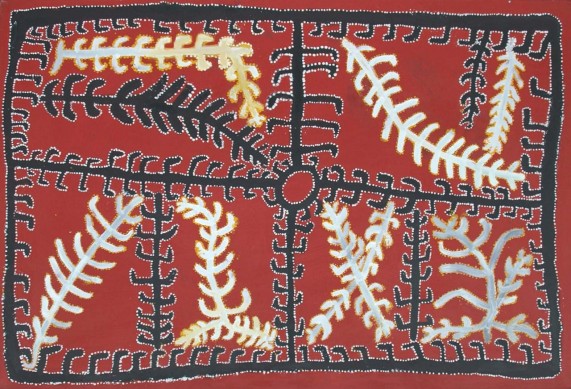

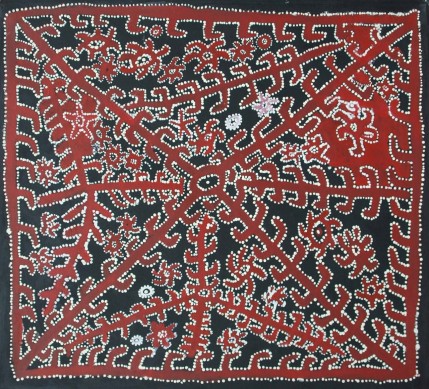

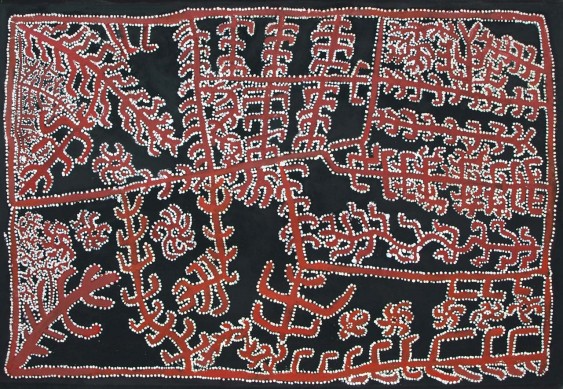

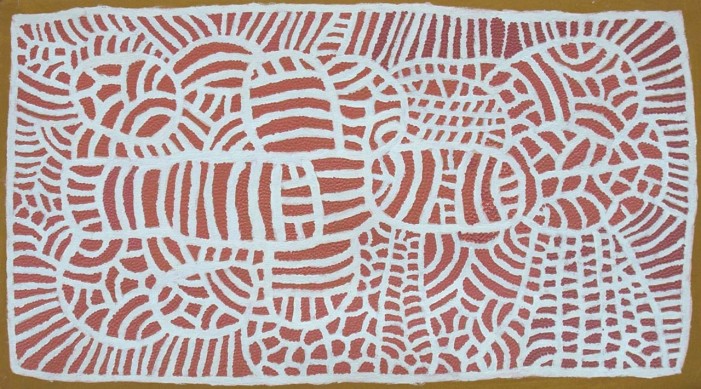

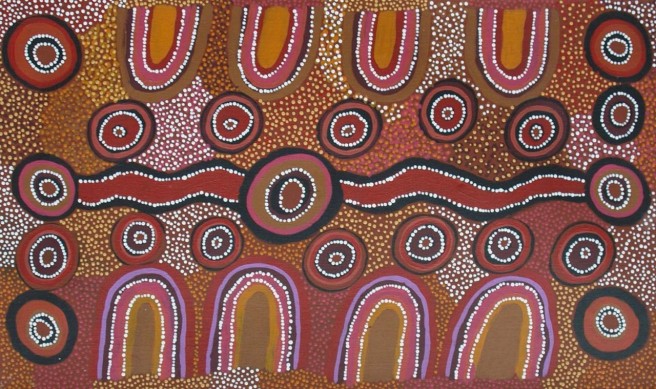

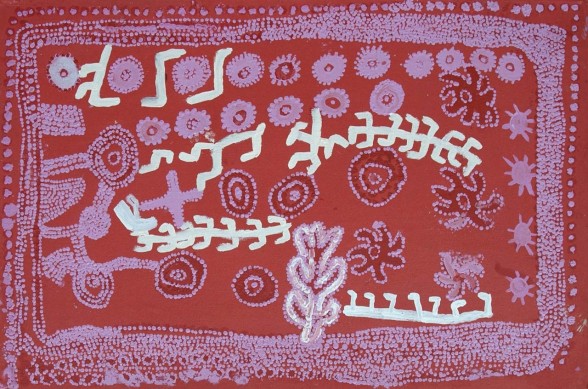

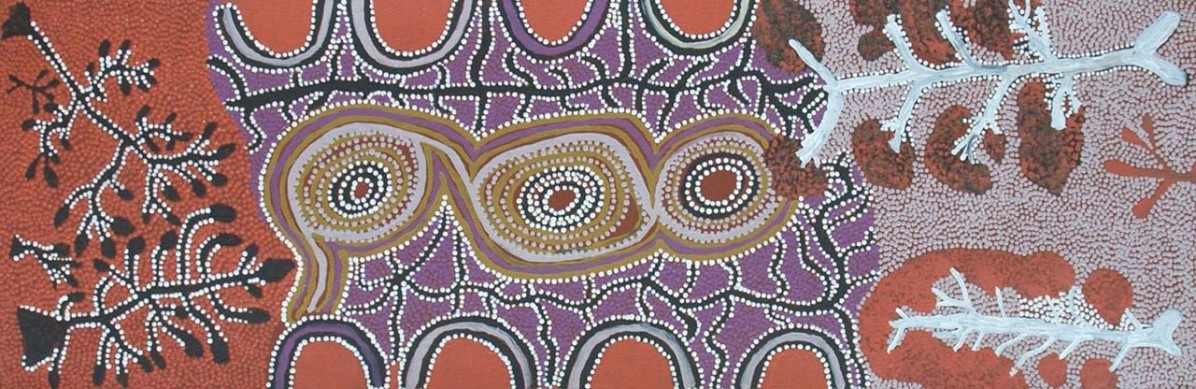

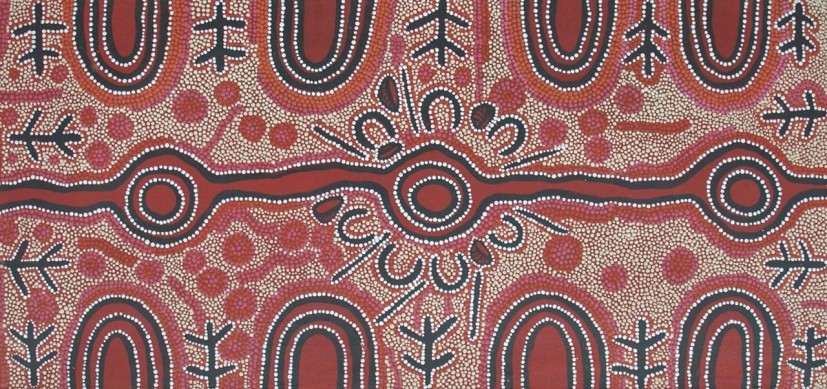

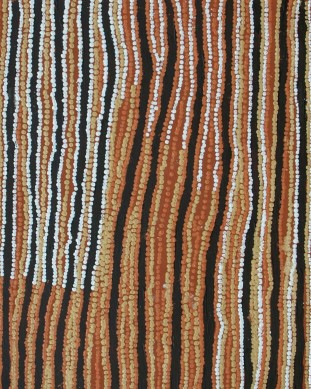

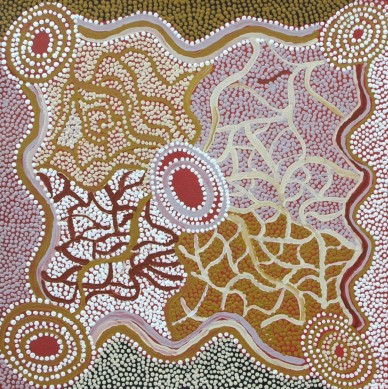

“I’m not allowed to do Tjukurrpa (dreaming) designs,” he says, “so I paint patterns of country from my mind” – generalised versions of the desert-crossing song cycles, sweeping topographies with an immediate appeal. His younger friend from stock-camp days, Mungkuri, joined him. Mungkuri has developed a different style: he often paints strong icons, sharp colours on dark ground, colours with the starkness of the country — and those colour rhythms form the essence of his work, fittingly for a man who started up the bush garden at nearby Mimili, and still strolls through the desert landscape like a master, watching the tracks, checking the waterholes, seeing everything.

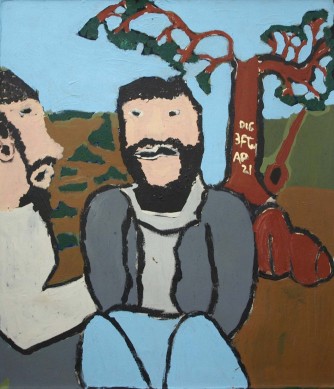

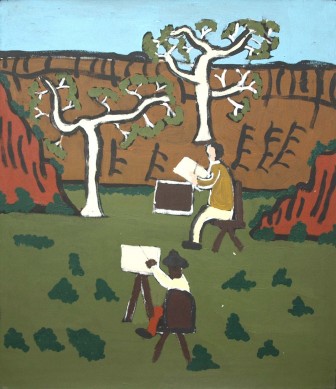

Now the two paint daily, side by side, in a bustling art centre complete with its own makeshift gallery. Iwantja Arts even has its vivid logo, a wide-eyed, staring owl: the emblem for the community since a lone boobook owl took up an unwavering perch on the gabled rooftop of the school. Close to the pair, at his own desk, bent over an unfinished canvas, is the wild card of Iwantja Arts, eyes distant, hand moving with gentle, certain motions: Tjukangku is increasingly frail these days, old age is claiming him — but the far past is very present in his mind, as are the symbols and designs he paints.

Tjukangku was born in the bush in 1939 and grew up on Ernabella mission and at the station just east of Indulkana, De Rose Hill. He is a full brother of one of the art stars of nearby Amata, colourist Barney Wangin. And Tjukangku, too, is a natural at adapting traditional motifs to canvas, at giving them force and movement in paint.

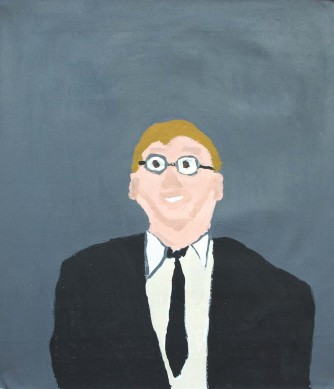

But this particular brilliant, late-blooming career almost didn’t happen. Tjukangku had sketched out a couple of pieces years before, and stopped. One of those works was still in the art centre, cast aside. It was rough and wholly figurative: kangaroos, trees. It had something. It caught the attention of Wayne Eager, a well-known western artist based in Alice Springs, who was helping out at Iwantja. He encouraged Tjukangku: “What about coming back to paint?” he’d say. “I’ve seen that work of yours, it’s a beauty.” And Tjukangku would say, “No, no. No painting, I’ve finished.”

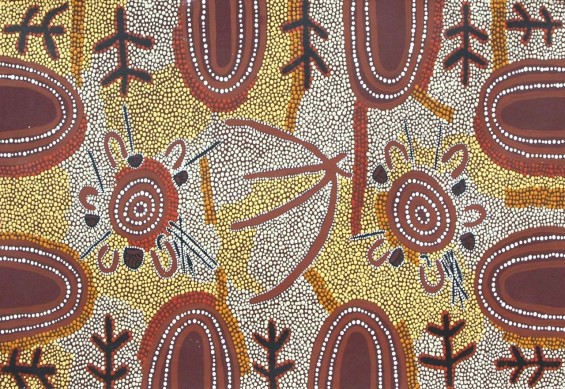

This exchange was repeated, on several trips Eager made, across many months — then, one day, Tjukangku started to paint again. It was a new style: deep ochre shades, dark grounds. The works drew the eye; their symbols stopped the heart. But what were they, exactly — those track-like converging lines, those curve-fringed stars, those hooked marks that seemed to race their way across the canvas? What? The art experts looked and wondered, and strange theories came to life.

Upscale city galleries began showing the Iwantja men. Tjukangku’s pieces seemed to lure in viewers and demand a narrative: something beyond the brief title invariably affixed to them: Arrernte Country, for the land he used to travel. The hooked lines were trees, perhaps, or references to the carved wooden objects that men made in earlier decades on the desert lands.

Some commentators took a realist approach and read the imagery as a stockman’s map, with the lines leading to a central roundel as homeward paths, or tracks to a great waterhole. Mossenson Galleries, early supporters of Iwantja art, wrote of Tjukangku’s “lyrical, free-form paintings, laden with waterholes, rockholes and scorched, fallen trees”, and conceived his works as acts of nostalgia, expressions of love for country.

But there may also be something else, as in most art made by senior desert men. Incautious travellers moving through the region’s ranges occasionally stumble across caves and rock shelters, and see their walls and overhangs inscribed with the same barbed lines that figure in Tjukangku’s works: see them, and retreat, for the context is plainly religious, the symbols have to do with ritual, and masculinity, not with growth and flourishing and form.

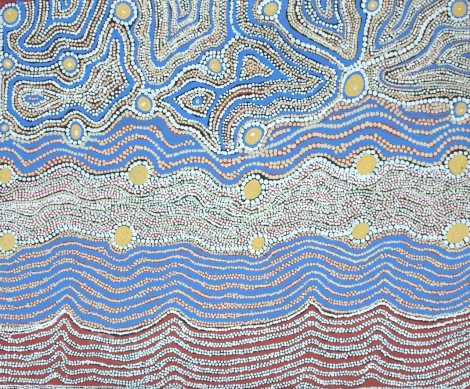

How, then, to proceed in understanding? The men at Indulkana guide their visitors freely through their country, dispensing clues to its structure and appearance, and describing its stories: trap-rock water here, a bush turkey living here, an ancestral event on that hill or range-line, linked to sites far away.

But always further knowledge hides beneath the surface, at once inviting and resisting curiosity, much like the icons on their paintings: both symbols and screens, inviting curious, fascinated interest and resisting it as well. Such is the pitch of much desert art of the present time, much of it being made in Pitjantjatjara country, the last desert domain to embrace painting on canvas for the wider world. Fierce contention swirls around this art, and around ways of managing its reception.

Some outsiders dream of using desert painting as a means of preserving culture, strengthening social capital, achieving economic development; some hope to archive the rich beliefs of old custodians before they die; some yearn to build great collections of dazzling beauty, mapping the song cycles that wind from coast to coast.

But for the old men at Indulkana, things are simpler. Art-making is a last ride, a last journey high in the saddle: it takes them through the heart of their elusive country in its various guises — it is their time and life and being made into paint.