Why Songlines Are Important In Aboriginal Art

Songlines are one of the many aspects of Aboriginal culture that artists draw on for inspiration. They are the long Creation story lines that cross the country and put all geographical and sacred sites into place in Aboriginal culture. For Aboriginal contemporary artists they are both inspiration and important cultural knowledge.

In this article, David Wroth reflects on what he has learned about songlines and how they are represented in Aboriginal contemporary art.

Creation Ancestors In The Creation Era

In traditional Aboriginal culture there is the belief in a creation era and creation ancestors. These ancestors traveled across the country creating the landscape, the animals and the law under which human society was to live. The journeys of these ancestors across the country make up a songline.

Song Cycles Pass On Cultural Knowledge From Ancestors

In Aboriginal culture these ancestral sacred stories are passed on as large song cycles. People might specialise in chapters or sections of a songline which tells the entire creation story that relates to a particular tract of land. People on neighbouring land will have the next chapters of what happened to the ancestors as they crossed over to their own part of the country.

In Aboriginal terms the kinship lineage of the ancestral people from that country, or the custodians, had control over that songline. It was their duty to uphold the obligations of passing the song on in perfect form to the next generation. In the initiation processes within Aboriginal culture each generation is taught the entire package of their culture over a series of stages of knowledge. Through these song cycles people gradually learn the entire cultural story of their people.

Songlines Define Groups And Responsibilities

A songline also defines a group of people in Aboriginal Australia. It defines the land that they live on. It defines the law that they live under. It defines the ceremonies and the obligations that they have in respect of their country and the sites located on their country.

Ancestor Journeys Create Common Ground

Neighbouring language groups are connected because song cycles weave and criss-cross all over the country. They share beliefs in the ancestors and the laws that relate to them. People were able to interact with their neighbours in terms of their obligations along those songlines. In some ways they also created the possibility of barter or exchange based on cultural knowledge between adjoining language groups.

Songlines Tie All Aboriginal Australia Together

Songlines can be mapped. It requires major consultation between neighbouring groups because there were several hundred language groups across Australia when white people first arrived here. Those language groups mostly define custodianship of songlines. Many of these songlines criss-cross in the sense that they go east and west and they go north and south and they go diagonally and they backtrack according to the journeys of the ancestors. They create a kind of cultural network of stories that ties all of Aboriginal Australia together.

The Significance of Songlines

Songlines underpin the whole Aboriginal culture. This is because the significant knowledge of culture that belongs to people comes from their participation in the songlines of their country. Those same stories are the family stories and the clan stories that become part of what people can paint when they start painting.

Songlines As Part of The Modern Painting

The modern painting movement has been a reflection of songlines. It is a more approachable way for Europeans to appreciate Aboriginal culture. Traditionally songlines were about language, song, dance and ceremony. Much of this was, and still is, secret sacred and therefore not visible to outsiders. At the same time, some of the significant parts of it were in the public domain. So when Aboriginal people started engaging in the contemporary art movement they were able to find ways to illustrate their history out of the songlines and put those stories into their paintings. The resulting art has spiritual and cultural content, which engages people even when they don't understand the significance or the detail of the story behind it.

How Is A Songline Represented In A Painting?

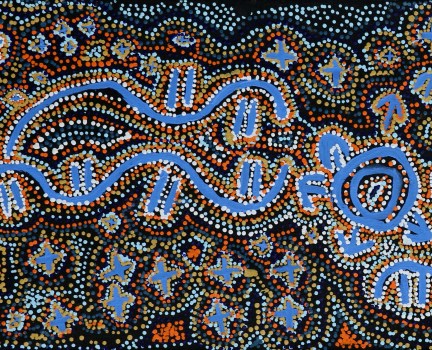

A songline might contain a whole series of incidents and a whole series of knowledge areas that are connected. Most paintings focus on one site within a songline. A songline going across traditional country may have twenty or may have fifty very important sites for a language group to maintain and to carry out the appropriate cultural protocols. Painters will often relate to the specific story that their family is custodian for. There is also an inherited skin name kinship structure that decides how things get passed down intergenerationally. A particular skin group along with a senior individual may be custodian for a particular site. The site sits on a songline which has a much wider spread of importance as it connections up with all the other groups who have responsibility along that songline for other sites. All of these are tied together with one ancestor story and one common narrative, the creation narrative.

Focus On A Location

Paintings done by traditional custodians and traditional people are very often about one of their sites of significance. Sometimes a painting can be about more than one of these locations. This is certainly true of people like the Tjapaltjarri Brothers - Thomas, Walala and Warlimpirrnga. They would often structure a painting that they called Tingari or Dreaming. Effectively the symbols represented a network of sacred sites that make a structure in a painting. Those structures are really the structures of a songline, the series of stories and ceremonies that were taught to those artists as part of their cultural obligations.

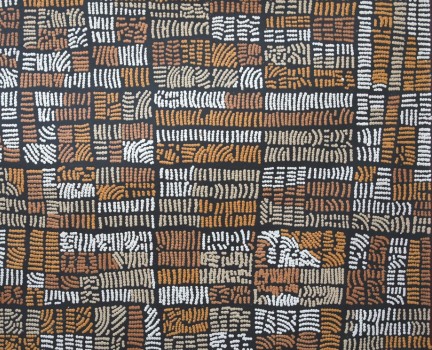

Songlines, Symbols And Structure

There are repetitive symbols sometimes used by artists when they are building a structure. You can notice this in the art of people like Ray James Jangala, Patrick Tjunurrayi and other Pintupi artists. You can see that there is a structure almost like an architecture or an engineering drawing, where there are symbols repeated across the painting to create a kind of network. That is a symbolic representation of the songline.

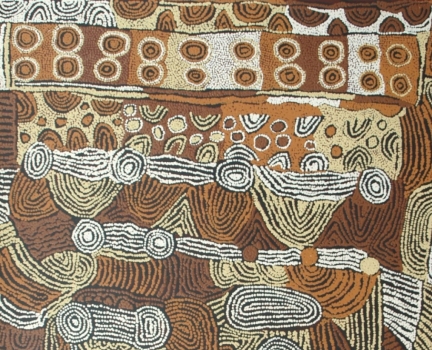

Central Desert Iconography

Another interesting example of symbolic representation of a songline is the iconography of the Warlpiri people. They use specific symbols to represent sites and ceremonial processes. If they're painting a ceremonial ground there might be a design that forms the pattern of movement of the ceremony. There will be perhaps two circles and a series of parallel lines connecting those circles, which is marking out the end points of the ceremonial ground, the way the ceremony is acted out on the ceremonial ground, and often there are symbols indicating if it's an emu dreaming or a water dreaming. This is how the artist expresses the symbolic connection to the ancestors.

Symbolic Language of Landscape

In contemporary Aboriginal painting there are also often structures that refer to the landscape. Some might refer to the hills or the rocky country or sand hills. There's references both to the nature of the landscape where the ceremonial site is, as well as the metaphysical ceremony that belongs in that landscape.

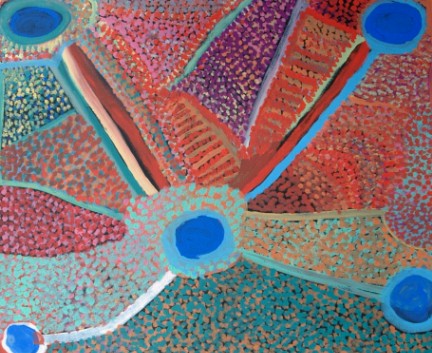

An example of symbolic language and landscape is Dorothy Napangardi's use of the Mina Mina Jukurrpa story. Mina Mina Jukurrpa is a major women's dreaming site in the Tanami Desert near salt lake country. Dorothy's mature paintings all showed the surface of the salt lake as the cracked patterns that happen on the land when crusts of salt absorb water and split. Her designs in black and white referred to the landscape and to the salt lake surface. In the way that Aboriginal people have layers of meaning in their paintings, it also refers to the salt lake country that's part of the Mina Mina Jukurrpa storyline, which in turn is part of her custodial rights.

Layers of Meaning Build With Cultural Knowledge

Aboriginal culture contains layers of meaning. As people are taken through the knowledge of their culture they are brought in at one level and then taken to more and more detailed and intricate levels of knowledge. When they are painting they can make a reference to the landscape or they can make a reference to the ceremonial ground, or they can make a reference to the bigger-scale structure of the storylines like some Pintupi artists do.

Landscape Seen Through The Context of The Songline

George Ward Tjungurrayi would paint vast tracts of his country. The repetitive patterning was really the songline overlay that sits on top of the natural terrain of the country. Aboriginal people see the country through the songlines and the ancestral importance of that country as much as seeing hills and valleys and plains. Traditional Aboriginal people see a physical landscape but all the significance in that landscape comes from what the ancestors did and then handed down to the people through the songline ceremonies.

The Singing Of Songlines

Traditional Aboriginal artists, immersed in the subject of their painting, will sometimes sing the song that applies to the subject they are painting. That conjures up the story, all the knowledge that relates to the place. It might also conjure up all the personal relationships they've had with family and other groups that all come together in those big ceremonies. They're very important social bonding processes. People remember all the people they've been with on these ceremonial grounds.

Young Artists And Songlines

The degree to which a young artist is influenced by traditional cultural knowledge varies greatly depending on the community they grew up in. People from places like Yuendumu are still closely in contact with those notions, have visited those sites, have participated in those ceremonies. That may well be less true of Aboriginal groups that have lived for generations in densely settled areas. Many of those ceremonies may not have been conducted for 50 or 100 years.

Perhaps the desert art movement, as it's happened across remote Australia, has reinforced the significance of songlines for younger people. Most successful desert artists have had very strong connections to their cultural heritage. A large part of the success of the senior Aboriginal artists has been based on their traditional knowledge. I think younger people have been able to see the prestige that comes both from within and beyond Aboriginal society from being a cultural elder and custodian. They have seen the recognition that can come from outside Aboriginal communities. They see their own community elders achieve worldwide fame by representing traditional cultural stories through their art.

Connection Between Powerful Art and Songlines

There seems to be a very strong connection between the power that comes from a painting and the power that an artist feels from being part of a songline and cultural knowledge. The energy and the spiritual impact that Aboriginal paintings seem to impart suggests that there's some deep and quite powerful source of inspiration or meaning coming from the subject matter that the artist is painting. This is certainly true of the first 40 years of the Aboriginal art movement.

Will these stories continue to inspire future generations of artists? Can these story-telling traditions be maintained into a modern world? There are many passionate people who believe so. What is certain is that no one could have predicted the widespread emergence of the contemporary Aboriginal art movement. No one could have guessed that it would be, and continues to be, celebrated around the world. Where you find deeply held cultural richness, integrity and passion anything is possible.

Read More: